Topshop: What happened after the shutters closed?

- Published

What happens to shop workers after the shutters are pulled down for the last time and the lights are switched off as another store closes?

What was once a bustling shop and a way of life for its workers is now left to a bunch of mannequins in darkness.

"It was just strange. It didn't feel real, locking the doors and saying goodbye and just thinking I'm never ever going to be here again," says Tamsin Lynham, who worked at the now closed Topshop in west London's Westfield shopping centre.

For the last week, when they were clearing out the shop, she says she cried every night on the way home on the Tube.

"It's the first time something like this has happened to me. I went into absolute panic mode. It wasn't really just a job, it was like you've got a little extended family. It was a huge part of my life," she says.

Tamsin is 35 and has been working in shops for more than half her life, starting at Topshop with a Saturday job when she was 16. The closure, she says, has been "heartbreaking".

Like so many people whose jobs have been threatened in the pandemic, Tamsin is standing nervously at a crossroads.

What happens next? Where will all the shop workers go if more retail jobs are lost? Who is going to retrain them? The closure of Topshop branches is a business headline, but it's also a piece of people's lives disappearing.

Will it be a case, to use the phrase attributed to football manager Tommy Docherty, that when one door closes… another one slams in your face?

According to Neil Carberry, head of the Recruitment and Employment Confederation, this is the "fastest-changing jobs market for a generation".

Recruiters have seen big collapses in demand in sectors such as retail, hospitality and the leisure industry - and growth in other areas including social care, construction and home delivery. The biggest year-on-year fall has been for bar staff, while demand has soared for bricklayers.

The impact of the pandemic cuts across generations. While mid-career shop workers are worrying about reinventing themselves, young people are struggling to get a first job.

Isabel Scavetta, aged 23 from Maidenhead, in Berkshire, has seen her expectations about jobs turned upside down. But not necessarily for the worst. "In some ways I'm strangely grateful for having to re-evaluate," she says, describing a "complete career pivot".

Isabel is part of Generation Covid, leaving university last summer. Or maybe it would be fairer to say that university left them, because their student days ended with such abruptness.

She has a degree in European social and political studies from University College London, but with so many graduate schemes closed by the pandemic, her direction "radically changed".

She taught herself coding and began volunteering work for an online project called Class of 2020, external, which provides free training for young graduates trying to get into work.

Her new digital skills have got her a paid internship in artificial intelligence at Rolls Royce, working remotely. "The entire trajectory of my career looks completely different from what I would have thought a year ago," says Isabel.

But she is keenly aware of how tough it has become in the quicksand of the current jobs market. Even knowing where to start can be overwhelming, she says, so that it becomes a kind of "decision fatigue that's almost paralysing".

Isabel Scavetta learned coding in the pandemic and completely changed her career direction

Deirdre Hughes, careers consultant and former chair of the National Careers Council, says it can feel very confusing for people looking for advice, particularly if they're shell-shocked as a result of a redundancy. "How do you take that first step?" she says.

She argues that there needs to be a public information campaign about where to find job advice - and warns the current system in England is too fragmented and "not good enough".

Tamsin from Topshop, is still trying to readjust to what's happened - and the loss of a job she "really loved". "I would never have seen that coming. I'm still in shock if I'm honest. I never thought there wouldn't be a Topshop on the High Street," says Tamsin.

"It's all I've ever known. I feel like I've been robbed, I had so many big plans. I put everything into that job, I really did."

Her colleague Milly Vaja, aged 27, says it is "mind boggling" to see such shops closing, and is still staggered by what has happened during the pandemic. High Street brands, as "unsinkable" as the Titanic, are disappearing.

Now Tamsin and Milly are facing tough choices. They say their main source of advice has been other people they've worked with.

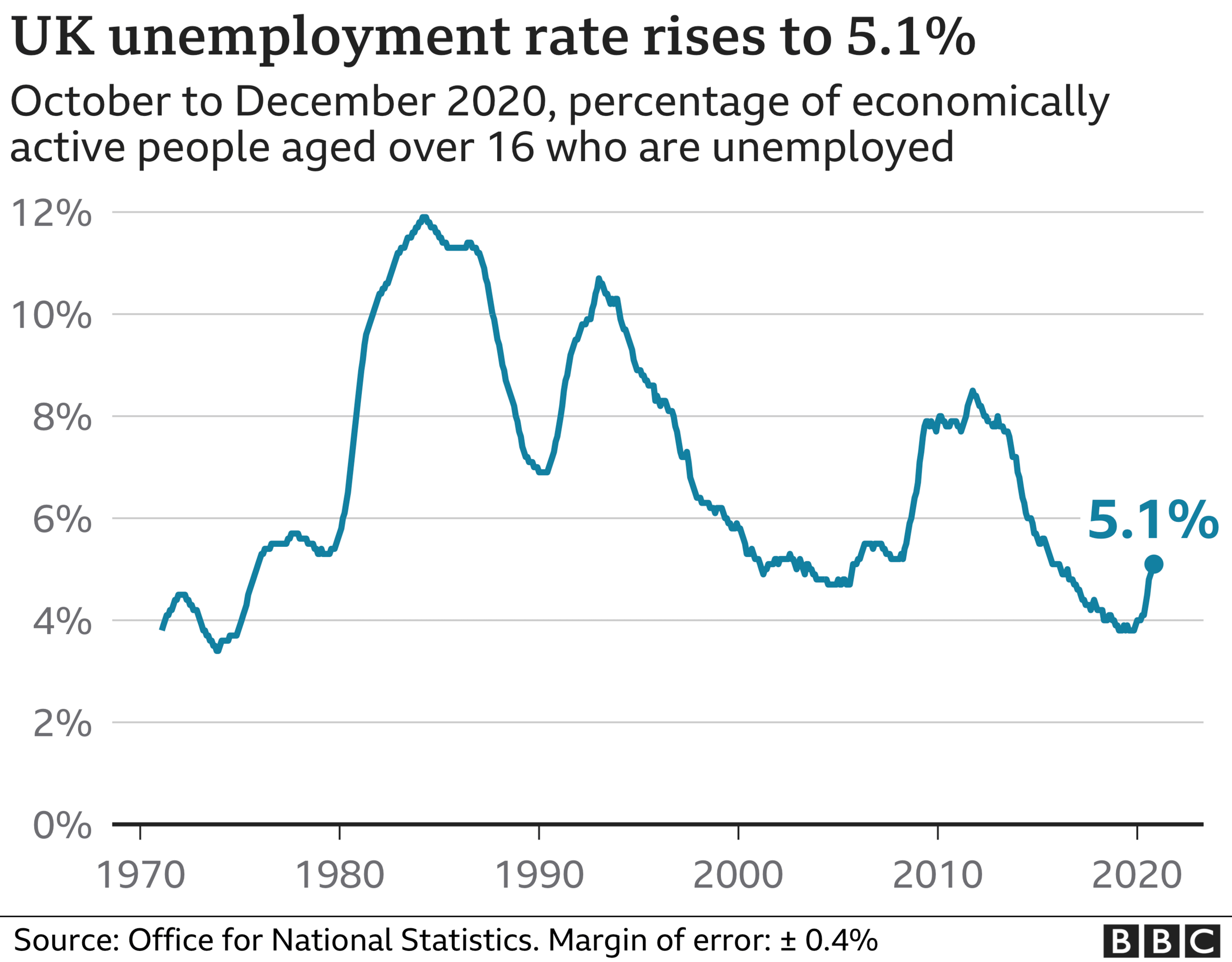

Redundancy rates are higher now in the pandemic, according to Office for National Statistics figures, than they were in the economic shockwave that followed the financial crash of 2008.

It's the end of an era for Tamsin and all her creative work on Topshop's shop displays

"Do I stay in retail? Do I stick with what I know?" Tamsin is considering whether it would be safer to move into more "high-end fashion".

"I absolutely loved it, but do I look for something else now?" says Milly.

Tamsin might make a complete change of direction and has thought about retraining as a dog groomer. "Where do I start? I haven't been to a careers advice person since I was at school," says Tamsin, who worked her way up to be the store's visual manager.

"A lot of people won't even look at your CV if there's no degree. It closes a lot of doors," she says.

She says other people in retail have retrained as carers, and is upset when she hears about former shop workers having applications turned down as they look for new careers.

"People need a second chance. It's not about whether they tick all the boxes," says Tamsin.

"The interview process is so hard, they make it so difficult. 'You need five years experience.' But how do I get experience if no-one gives you a chance?" says Milly.

She is moving out of London to Leicester, to get an affordable house, but that means finding a secure job for the mortgage.

Milly says she'd booked an interview for packing orders for a delivery firm but decided that wasn't for her, and went back to searching online for other jobs. Her life is suddenly full of uncertainty, and she's not alone.

The recruitment website LinkedIn says it has seen a 24% year-on-year drop in hiring for retail jobs, with jobs in recreation and travel even harder hit, down by 52% compared with January 2020.

The biggest two growth areas for jobs are in healthcare, up 28% year-on-year, and transportation and logistics, up 11%. All those deliveries at the door are a warning bell for a changing jobs market.

Amina Dahir, in Birmingham, is one of those people changing to become a carer. Her job as a cleaner in a shopping mall disappeared in the lockdown.

"It was really hard, but we just had hope that it was going to come back. But it's like there's no more security, if you understand. That's how I felt," says Amina, 40. "So many people have lost their jobs."

But she's got a positive new direction. A work coach at the JobCentre Plus directed her to the care sector and the free training available. She says it will be rewarding to care for old people as well as getting qualifications for a more secure job.

Amina expects it to be even harder after the pandemic, with more people chasing fewer jobs. "When you lose your job you need training. You don't know what happens next. Lots of people don't even know where to look," she says.

Careers week

Ten tips for getting your dream job

Across BBC News, as part of National Careers Week, we're hearing from people at a crossroads in their career and will aim to give tips and advice.

As part of the week, BBC 5live's Naga Munchetty will host a careers clinic from 13:15-14:00 GMT on Tuesday 2 March on the BBC News LinkedIn page, external.

Amina's training, funded by the government, is being carried out by the adult education organisation the WEA, the Workers Educational Association, which has trained 36,000 people during the pandemic.

"It's worrying and frightening for many people at the moment, given the rapid rise in unemployment," says Simon Parkinson, the WEA's chief executive.

"It's hard enough at any stage of your career, but if you've been in a single industry for 15 or 20 years, it's devastating."

He says there can be stress and anxiety that starts "spiralling downwards". The challenge is to turn this round, he says, and show the "world of work has changed massively" - and there are new opportunities.

"It's about raising people's confidence, reminding people it's not too late. They need food on their table. They're the engine room of the economy. It's not the graduate jobs, it's the millions of people, 35- to 55-year-olds, that have worked in some of the backbone sectors of the country."

He says very practical barriers to recruitment are often overlooked - such as everything being online, including Zoom interviews. "It is not true to think that everybody in the country has got a solid broadband connection and access to a laptop."

Shanique says she has applied for more than 50 graduate jobs

While Amina was looking for training after losing her cleaning job, across the city Harriet Ferguson was graduating from the University of Birmingham.

"It's hard to know what's available," says the 23-year-old, "and you can't go to careers events to go for an interview and meet people." She been job hunting in the pandemic.

Employment figures in February showed it was her age group that has been hardest hit - with almost three-fifths of job losses falling on the under-25s.

Harriet, from High Wycombe, wanted to work with young people and has got a six-month contract with the St John Ambulance cadet programme.

But she is concerned about other young graduates struggling to find jobs, with worries about loneliness and being "completely in the dark" about what comes next.

She has been volunteering to help other young jobseekers on the Class of 2020 website, and hears about their problems.

"It's so isolating," she says. "The standard story is people sending in hundreds of applications. There's the sense that it's only you that's struggling, trying to be resilient, when it's rejection after rejection after rejection."

Where do you start?

The pandemic has also shown up the vulnerability of those relying on insecure, temporary contracts.

Ritu Panchal worked regularly for years as a teaching assistant, but through an agency. When her work in schools suddenly stopped in the lockdown, she had nothing to replace it.

"I didn't expect to be like this," says the 43-year-old from Hemel Hempstead. "I never missed a day. Wherever they told me to go I went."

Ritu is training for qualifications to improve her chances of getting another teaching assistant job on a more permanent basis. A theme that keeps recurring, for young and old job hunters, is the uncertainty about where to get advice.

There are no shortages of warnings about a "perfect storm" for jobs in the pandemic, but where do you look for the rescue boats?

There are thousands of retraining courses offered online - many of them expensive - but which ones are really going to make a difference?

Amina, part of the wave of people being retrained as carers, says advice should be offered when people are still working, before "waiting for a crisis to come".

There is a wider issue of how much has been invested in adult careers advice, whether it has been taken seriously and how it is delivered.

A probably apocryphal story, suggesting the lack of priority, is that when a senior minister was asked about careers advice, he joked that if careers advisers were so good how had they ended up as careers advisers?

Many retraining schemes are reached through the Job Centre Plus system, including for those in work. Simon Parkinson at the WEA suggests there should be more ways of "connecting with people".

"People don't necessarily want to walk straight into a Job Centre. Particularly older workers, if they managed to come through the 1980s," he says.

There are a growing number of government responses. The National Careers Service, external has free advice and a helpline, there's a Skills Toolkit, external to find courses and 16-week "boot camps" teaching specific skills, such as coding and software development.

Starting next month, the government's "lifetime skills guarantee" will include 400 free training courses for adults whose qualifications are below A-levels, in areas such as social care, childcare and construction.

Under the "Plan for Jobs" scheme, there are initiatives such as Kickstart to create new jobs for 16- to 24-year-olds and Restart, which will have £400m in 2021-22 to provide support for the unemployed.

Shop workers who have seen their store closing down will now have to start again

For Tamsin Lynham, her shop is gone but she says she's feeling more positive and getting out her CV. "To be honest, it's been a hard year."

She remembers the moment when they had a last cheer as they shut the shop, and the sadness afterwards.

"You think about all the people you've worked with, it was such a great place to work. I thought to myself: 'How much did these four walls stress me?'

"And people will think we were only selling clothes."