Integrated review: UK to lift cap on nuclear stockpile

- Published

- comments

Boris Johnson: "We will... relearn the art of competing against states with opposing values"

The UK is set to reverse plans to reduce its stockpile of nuclear weapons by the middle of the decade, as part of a foreign policy overhaul.

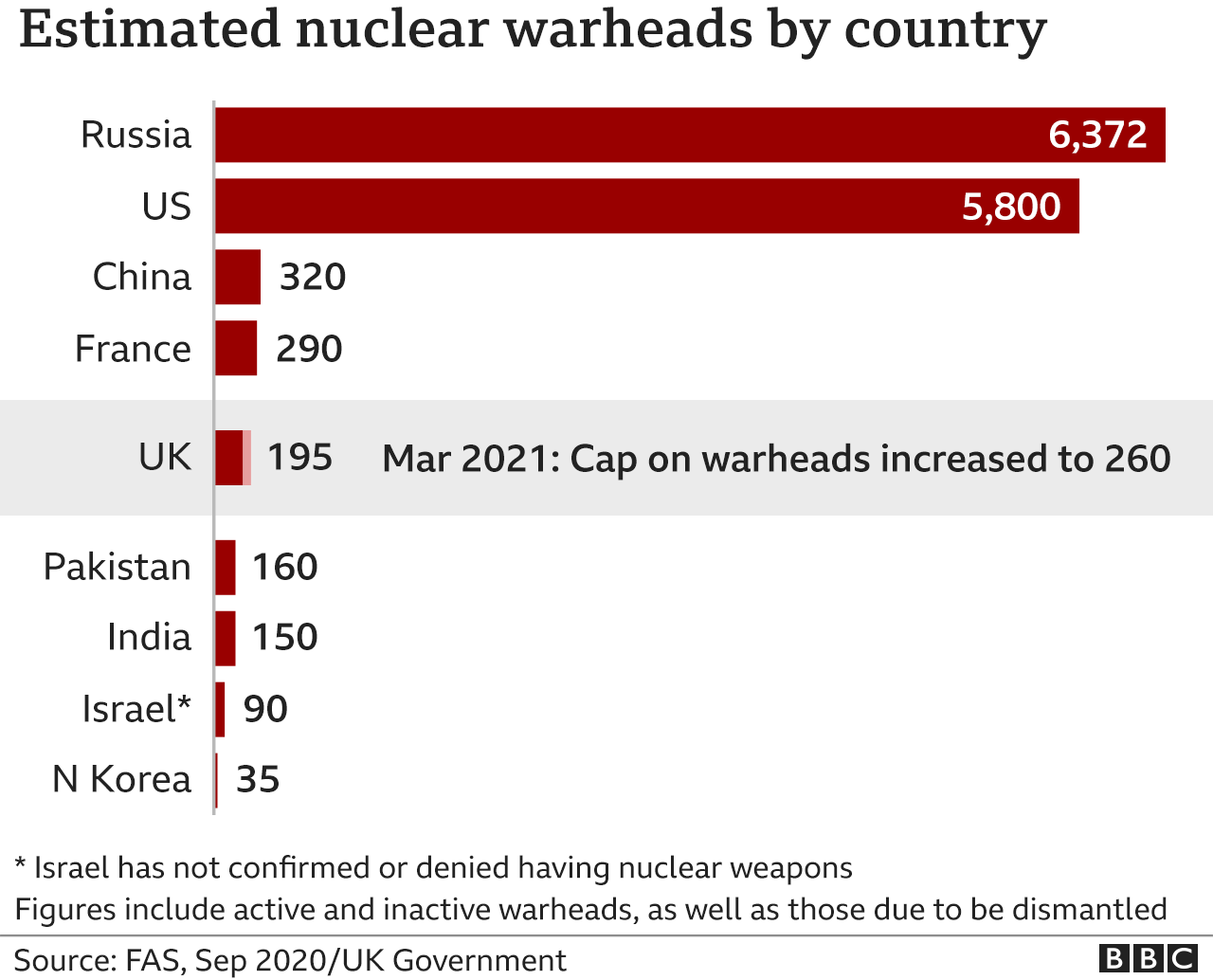

The overall cap on the number of warheads will now increase to 260, having been due to drop to 180 under previous plans from 2010.

The UK will shift focus towards Indo-Pacific countries, described as the world's "growth engine".

And it pledges the UK will do more on the "systemic challenge" of China.

Outlining the strategy to MPs, Boris Johnson said the UK would have to "relearn the art" of competing against countries with "opposing values".

But he added the UK would remain "unswervingly committed" to the Nato defence alliance and preserving peace and security in Europe.

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer accused the Conservatives of overseeing an "era of retreat," with armed forces cuts "every year for the last decade".

The integrated review, external of foreign and defence policies, which runs to over 100 pages, has taken over a year and sets out UK priorities until 2030.

The UK nuclear stockpile is estimated to comprise 195 warheads, and had been due to fall to 180 by the mid-2020s under a 2010 defence review.

But the latest assessment says this ambition is "no longer possible" given the "evolving security environment" over the last decade.

It adds that the UK will no longer publish figures on the size of its operational stockpile, to maintain "deliberate ambiguity" for adversaries.

However, it pledges the UK will maintain the "minimum destructive power needed to guarantee that the UK's nuclear deterrent remains credible".

The review, which identifies Russia as the "most acute threat" to UK security, also says:

It is "likely" that a terrorist group will launch a successful chemical, biological or nuclear attack by 2030

The UK will set up a new counter-terrorism operations centre to improve the response to terror attacks

The government wants the UK to become a "science and tech superpower" by the end of the decade

The review also pledged to reverse cuts on foreign aid, from 0.7% of national income down to 0.5%, when "the fiscal situation allows".

The government has previously faced criticism for the cuts, which it said were necessary in the wake of financial challenges posed by the Covid pandemic.

The review argues the UK should refocus its foreign policy towards countries such as India, Japan and Australia in the "Indo-Pacific" region.

It said the region's shipping lanes were vital to maintain UK trade with Asia, whilst the region is also on the "frontline of new security challenges".

What does the review tell us?

Analysis by Rob Watson, BBC World Service UK Political Correspondent

What's striking about the review is the continuity in UK foreign policy.

So just as before Brexit and "Global Britain", the UK continues to see the main threats to its security as China, Russia, terrorism and cyber attacks. And it continues to have as its main goals, among other things, the promotion of democracy, free trade, human rights and the fight against climate change.

There are differences, though. The most striking is the suggestion of a pivot away from Europe to the Indo-Pacific.

But exactly what that means is not spelled out (although we do know Boris Johnson will travel to India next month, and there will be new focus on new partnerships and trade agreements with south-east Asian countries).

More broadly, Mr Johnson's central claim is that leaving the EU will make the UK more nimble and flexible, whether it's in how to deal with China or becoming a science superpower or anything else.

Critics will say the review is long on aspiration and that the UK will face the same global challenges it faced before Brexit - but with one fewer foreign policy tool in its toolbox, namely its membership of the EU.

Mr Johnson said: "The review describes how we will bolster our alliances, strengthen our capabilities, find new ways of reaching solutions and relearn the art of competing against states with opposing values."

He said the UK had led international condemnation of China's "mass detention" of Uighur people in Xinjiang, and its actions in Hong Kong, adding: "There is no question China will pose a great challenge for an open society such as ours."

In response, Sir Keir said UK policy towards China had been "inconsistent" and the government had "turned a blind eye" to the country's human rights abuses.

He said Labour remained committed to retaining nuclear weapons, but said the document had failed to detail the "strategic purpose" for increasing the warhead stockpile.

Sir Keir Starmer: "This review breaks the goal... to reduce our nuclear stockpile"

SNP Westminster leader Ian Blackford said the review demonstrated "just how hollow the brand of Global Britain is".

He also asked the prime minister "who gave his government the democratic right to renege on the UK's obligations under the nuclear proliferation treaty" referring to the government's plans on nuclear weapons.

Speaking to the BBC, Beatrice Fihn - head of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons - described the UK's decision to change its nuclear provision as "outrageous, irresponsible and very dangerous".

She said it went against international law and didn't address the real security threats faced by Britain such as climate change and disinformation.

Tory disquiet over China position

Analysis by Damian Grammaticas, BBC political correspondent

The review calls China the "biggest state-based threat to the UK's economic security".

But there is clearly disquiet among the government's own MPs that it hasn't been robust enough in identifying the challenge posed by its Communist regime.

Former Conservative foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt said he was worried by its description of China as a "systemic" challenge, given its current clampdown on Uighur Muslims and democratic rights in Hong Kong.

Another senior Conservative, Julian Lewis, took issue with its description of China as a "partner".

He added it suggested the "grasping naivety" of the party's approach under David Cameron and George Osborne, when it actively sought Chinese investment, "still lingers on".

Boris Johnson said there was a "balance to be struck", and although the UK wanted a "strong trading relationship," it should be "clear-eyed" and "tough where we see risk".

But the trade-offs between seeking investment and protecting the UK from becoming too vulnerable to Chinese economic and political influence and pressure will come under increasing scrutiny.

Related topics

- Published15 March 2021

- Published24 February 2021

- Published19 November 2020

- Published26 February 2020