Hate crimes on police 'more likely to be charged'

- Published

Police officers reporting hateful abuse while on duty are much more likely than members of the public to see their attackers charged with hate crime, according to an investigation by BBC Newsnight and the Law Society Gazette.

The new figures, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act from some of the largest forces in England, show that police officers and staff were the victims in up to half of the hate crimes charged in some areas, despite making up a tiny proportion of the overall number of recorded cases. The vast majority are serving officers.

Police forces say the increased use of body cameras by officers may mean evidence of hate crimes against them is more easily captured.

But hate crime victims and experts have expressed concern about the data obtained by the BBC.

It suggests that prosecutions for hate crimes against officers are dominating case work at a time when the overall number of complaints is skyrocketing and the number that result in charges is falling.

Just 7% of the 4,636 hate crimes recorded by West Midlands Police in the year ending March 2020 involved a police victim.

But the police were victims in 43% of the 711 hate crimes charged in the force area that year.

Data from three other forces paints a similar picture. The Metropolitan Police recorded 21,948 hate crimes in 2019/20, 4% of which involved police victims.

Just 1,762 cases resulted in charges, but of those 29% had police victims.

In West Yorkshire, 4% of the 8774 recorded hate crimes involved police victims, compared to 33% of the 694 hate crimes charged.

And in North Yorkshire, 53% of the hate crimes charged involved police victims. The force did not provide figures for the overall cases recorded.

Hate crime victims have accused the police of treating cases against officers more seriously.

Michael, who wanted to be known only by his first name, suffered a vicious homophobic attack in Birmingham in September 2018. He told Newsnight that West Midlands Police let him down by failing to investigate.

Michael was the victim of a homophobic attack in Birmingham in 2018

Michael was walking home alone after a night out with friends in the city's gay village when he saw a group of people on the pavement outside a straight bar. As he passed, he said, a woman shouted a homophobic slur at him.

"So, I stopped, turned around and I thought, well, I'll go back and, you know, ask her why she's called me [that], but even before I could reach her, someone threw a glass or a beer bottle or something against my head. And then I blacked out."

When he regained consciousness he had blood all over his face. He believes he was kicked in the head while on the ground.

West Midlands Police allocated an officer to the case and gave him a crime reference number in the days after the attack. The force told him it had requested CCTV from a straight bar nearby which had a camera overlooking the attack location. But, he told Newsnight, he heard nothing from police after that.

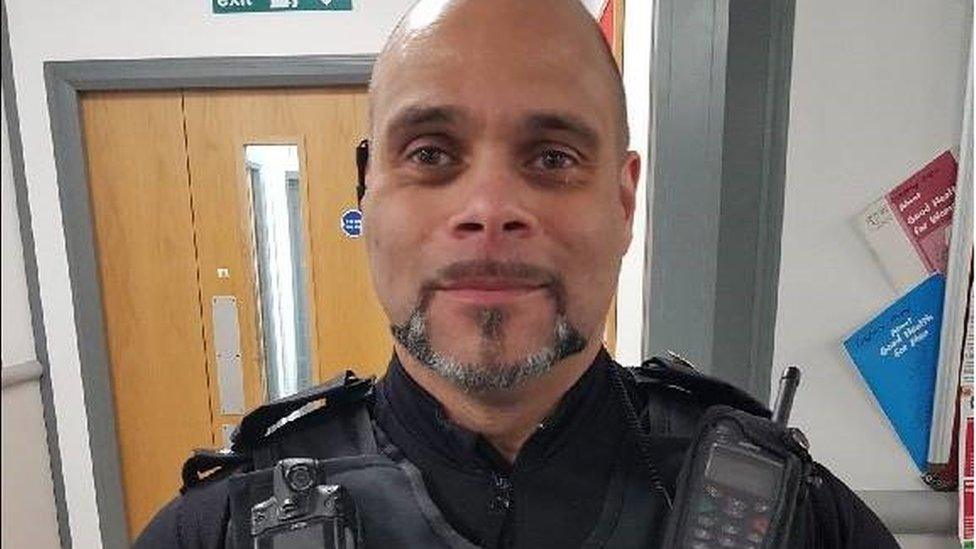

Chief Superintendent Mat Shaer, West Midlands' hate crime lead, admitted the force had got it wrong. He told the BBC: "We requested CCTV from the bar but none was provided. The matter was later filed.

"We should have done more to follow-up that CCTV request and provide the victim with a better level of service."

The force said it had since changed its hate crime policy to ensure Michael's experience is not repeated.

Michael told Newsnight that the police apology made him angry because "these are the people you go to for help".

When Newsnight told him about the new data showing 43% of hate crimes leading to charges in the West Midlands area involved police officers as victims, he said: "It's almost like they prioritise their own claims…They're putting themselves first."

Police admitted more should have been done to follow up on the attack against Michael

Chief Superintendent Shaer, denied this. "We do not prioritise hate crime investigations against our own staff," he said. "All allegations are investigated to the same set of standards and with impartiality."

He added: "Offences against our staff will not be tolerated, they are obliged to record the offences and we will always look to prosecute crimes against them."

He said the statistics might be explained by evidence from body-worn cameras.

"With the increased roll-out of body-worn cameras in recent years, hate crimes against our officers and staff are likely to be recorded on video. That is strong, irrefutable evidence."

He added: "Many hate crime offences against officers are committed after a suspect has been arrested for other matters so they are already in our custody when the hate crime is committed."

Many forces, including West Midlands, have adopted policies on hate crime against officers, which say these will not be treated as "secondary to other offences" and that the chief constable will provide a personal impact statement for each case.

Professor Neil Chakraborti, director of the Centre for Hate Studies at Leicester University, said: "I don't think this will do anything to build up levels of trust and confidence within communities who already feel stigmatised," said. "There are tensions between the police and particular communities and groups and a disparity like that does nothing for those kinds of tensions."

UNDERCOVER OAP: An 83-year-old widower becomes a spy for an undercover operation

TAKING ON THE COVID SCAMMERS: "Scammers target world events and take advantage of people's fears"

Related topics

- Published21 May 2021

- Published10 October 2020