Martin Bashir inquiry: Diana, the reporter and the BBC

- Published

Twenty-five years ago, the BBC's Panorama programme landed a scoop rivals the world over wanted - an interview with Diana, Princess of Wales. Her son and heir to the throne, Prince William, has now launched an unprecedented attack on the corporation over that interview.

The programme, which attracted a UK audience of 23m, was a career-defining moment for reporter Martin Bashir.

But after accusations resurfaced last autumn that Bashir misled the princess to gain her trust, the BBC established an inquiry led by the former Supreme Court judge Lord Dyson. That inquiry has judged Bashir to be "unreliable", "devious" and "dishonest."

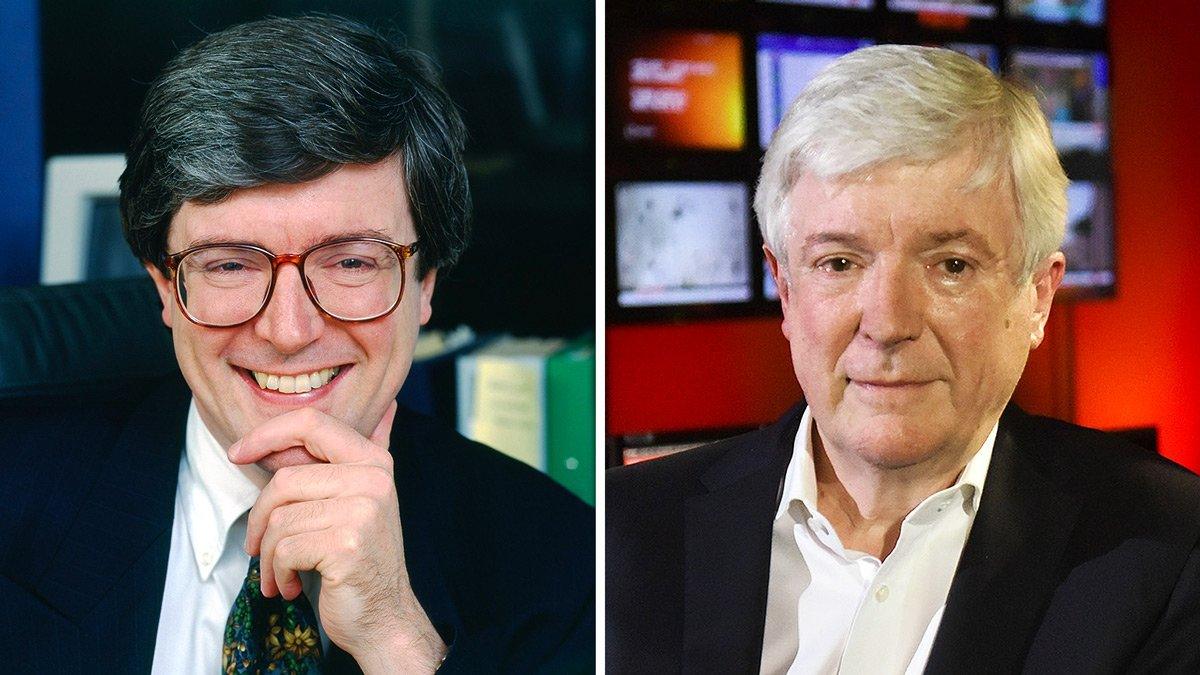

Bashir was investigated by the BBC at the time by Tony Hall, who went on to become the BBC's director general. Hall found that Bashir was "honest" and an "honourable man". Dyson has condemned Hall's inquiry as "flawed" and "woefully ineffective".

Until now, the full story behind the scoop has remained hidden for a quarter of a century.

The interview became one of the 20th Century's seminal TV events. As the separated wife of the future king, Princess Diana spoke of adultery, palace plotting, mental and physical illness, and how Prince Charles was unfit for the job.

"Do you really think a campaign was being waged against you?" Martin Bashir asked Princess Diana, having spent the preceding weeks amplifying the alarm bells in her head about just such a campaign. He claimed uniquely placed sources were telling him about dirty tricks by journalists, royal courtiers, the intelligence services, and even her friends.

"Yes, I did," replied Diana.

I worked on Panorama in 1995, and I had heard the rumours that Bashir had used deception to land his scoop, but nothing more. The details only began to resurface last autumn, on the 25th anniversary of the interview. The BBC released to ITV and Channel 4 some of the information journalists had been seeking for years.

At the same time, Princess Diana's brother Charles Spencer disclosed that he'd kept contemporaneous notes of his meetings with Bashir, and the claims he made.

Lord Dyson's report represents the BBC's formal response to the allegations against Martin Bashir and the failure of Tony Hall's 1996 inquiry to get to the bottom of this affair.

However, so serious were last autumn's renewed allegations of misconduct that the current Panorama team decided this needed to be investigated by the programme itself to restore public trust in Panorama's journalism and independence.

We've talked to almost all the witnesses who have given evidence to Lord Dyson and many more besides, including detailed testimony from Earl Spencer.

Like Lord Dyson, we have also seen internal BBC documents that not only show Bashir repeatedly lied, but also acknowledge that there was a serious breach of journalistic ethics and BBC rules. And yet the BBC management board was told by Hall that he was certain Bashir had not set out to deceive, while Hall's note intended for the corporation's governing body said he was an "honest and honourable man".

Lord Dyson says: "What Mr Bashir did was not an impulsive act done in the spur of the moment. It was carefully planned… What he did was devious and dishonest."

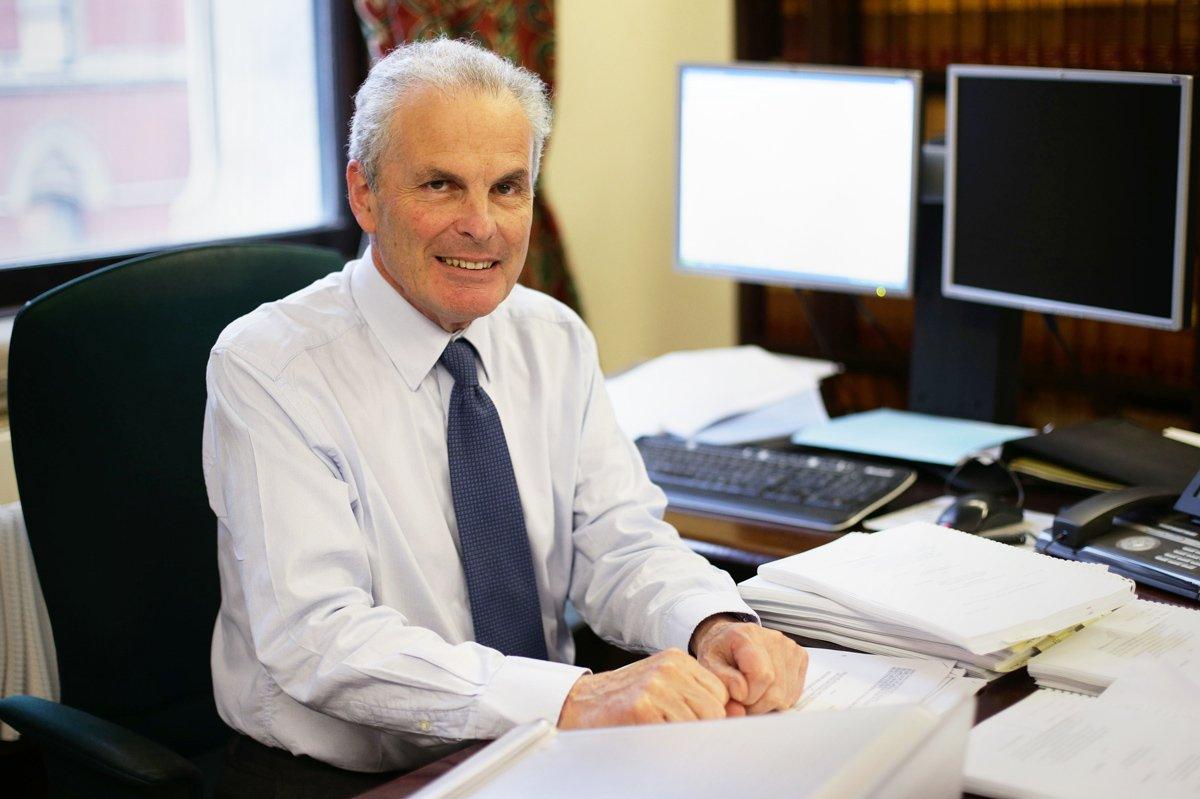

Bashir contacts Earl Spencer

The story begins with Bashir's plan to persuade Princess Diana's brother Earl Spencer that among journalists covering the "War of the Waleses", he had access to high-level sources with the inside story of a broad conspiracy against him and his sister.

On 24 August 1995, Bashir left a telephone message with one of Spencer's assistants: "Not seeking interview or info", just "15 minutes of time to talk". He then sent a BBC headed letter claiming to have spent the "past three months investigating press behaviour". In fact, Bashir had spent much of that time working on other Panorama programmes. However, his letter intimated that a dogged investigation had unearthed something big about press intrusion into the Spencer family.

"I simply [want] to share some information which I believe, may be of interest," he wrote, calculating Spencer would bite knowing that he had had his own battles with the media. With no response, Bashir called again on 29 August. Spencer said he could meet him in London at 18:00 for a quick drink.

Martin Bashir (1995) and Earl Spencer (1993)

On the face of it, the suddenness of Spencer's invitation to a meeting may well have taken Bashir by surprise. In order to ingratiate himself with Earl Spencer to gain access to his sister, the reporter intended to show Spencer - falsely - that his former head of security, ex-soldier, Alan Waller, was being paid regularly by Rupert Murdoch's News international and the intelligence services to spy on the Spencer family. However, Bashir didn't show this to Spencer at their first brief meeting - presumably because he hadn't yet created the "information".

Lord Dyson said he could not be certain about the precise date when this "information" was created. However, our own investigation suggests this happened immediately after Bashir's introductory drink with Spencer.

Spencer had agreed to continue their conversation at his country estate, Althorp, two days later at 11:30 on 31 August.

The fake bank statements

To help prepare the "information", Bashir made an urgent call to a former colleague, Matt Wiessler, begging him to drop everything for a job that couldn't wait. The graphic designer doesn't recall the exact date except that it was at the junction of August and September. Wiessler's business partner at the time told me that Bashir called him first and remembers it being around the time of the Notting Hill Carnival, which in 1995 ended on 28 August. He says that because Bashir wanted a rushed overnight job, he couldn't do it and suggested he call Wiessler instead.

Both Wiessler and his business partner are also clear that the call came after hours. Since Spencer's diary shows he had his first meeting with Bashir on the evening of the 29th, the evidence points to Bashir having called Wiessler soon after his drink with Spencer.

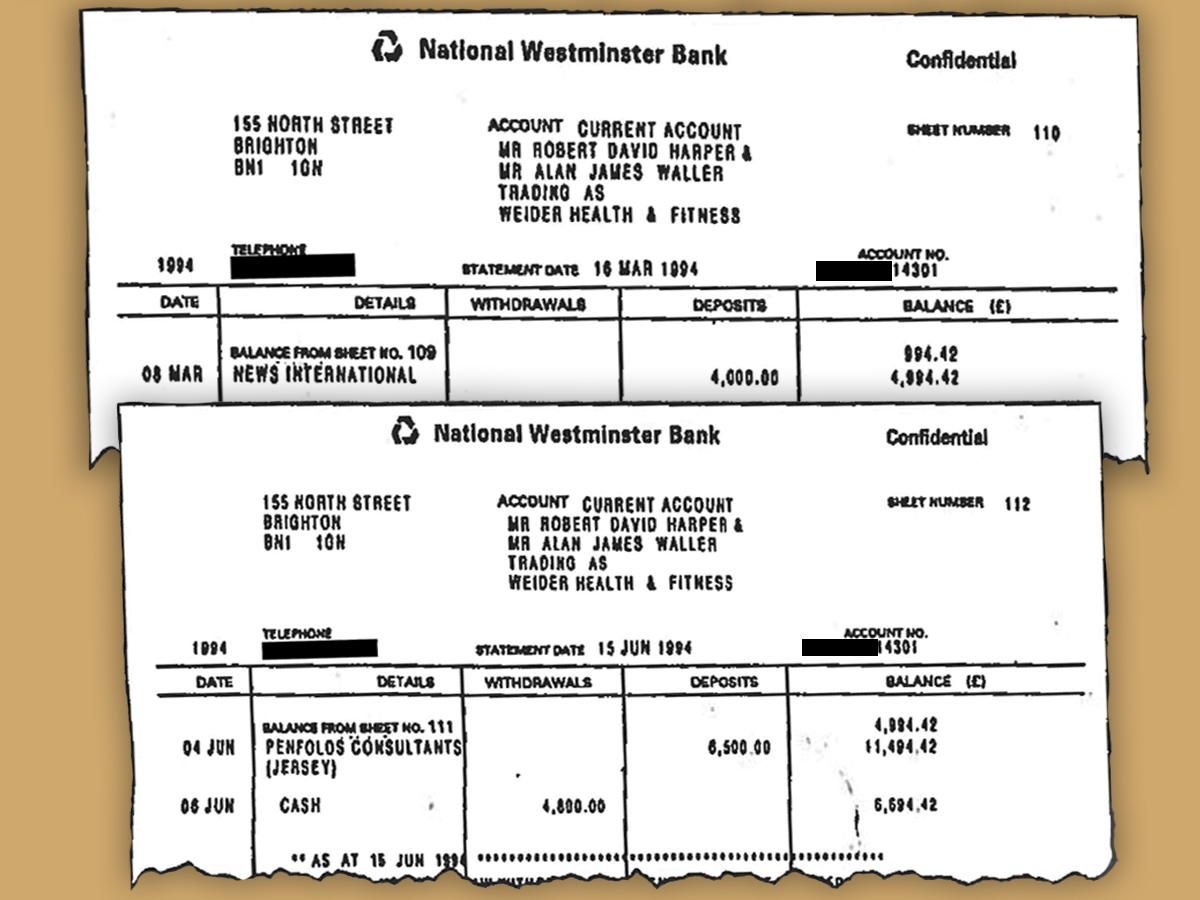

Wiessler says Bashir came to his flat and dictated from his notebook details of what he said were two of Alan Waller's bank statements, which he claimed to have seen - £4,000 from News International on 8 March 1994, and £6,500 from a Jersey-based company called "Penfolds Consultants" on 4 June. Bashir didn't mention the story he was working on was about Princess Diana, only that it "could lead to something big" in relation to "surveillance by MI5 or MI6".

The designer assumed that Bashir had actually seen Waller's original bank statements. He told Bashir the job of recreating them would take all night. Wiessler says that since Bashir was due to fly somewhere the following morning, he instructed him to courier the graphics to him at Heathrow at 07:00. Presumably Bashir wanted them ready for his trip to Althorp first thing on the 31st.

The fake bank statements

Spencer's note of that meeting shows that Bashir mentioned "payments" to Waller, which he said were regular: "8/3/94 £4K News International £4K quarterly" and "4/6/94 £6.5K Penfolds, 4 payments". "Penfolds Consultants", said Bashir, was a Jersey-based front company for the intelligence services.

What had really hooked Spencer, however, was another false claim by Bashir - that the private secretary of Prince Charles, Commander Richard Aylard, was conspiring against Diana. Spencer's notes show Bashir having claimed that Aylard had been handed secretly recorded conversations and, in an apparent reference to the possibility of divorce, told journalist Jonathan Dimbleby: "We are in the end game. Shit or bust."

Spencer says this knocked him sideways so he called Panorama editor Steve Hewlett. Although Spencer didn't list Bashir's claims to Hewlett, he did ask him if he could be trusted. Hewlett, according to Spencer, assured him that Bashir was "one of my best".

Bashir is introduced to Diana

On 14 September, Bashir and Spencer met again at Althorp. Bashir now ramped up his allegations: Diana's own private secretary Commander Patrick Jephson was said to be in cahoots with Aylard. Bashir produced what Spencer describes as a folded A4-sized sheet of paper purporting to show sizeable payments to both Aylard and Jephson from the intelligence services to monitor Princess Diana's movements.

In evidence to Lord Dyson, Bashir categorically denies he showed any such document to Spencer. However, Spencer noted the following comment from Bashir: "Patrick Jephson was a gd friend of Aylard + had business connections until 1992. Non exec director of company that Aylard was on board of Financial investment co. Jephson cashed in shared +resigned in 1992."

This echoed Diana's well-publicised fears of a conspiracy by her estranged husband's camp at St James's Palace to discredit her.

Because Spencer could make no sense of such alleged treachery, he thought his sister should hear all this directly from Bashir, so he telephoned her to suggest that she should meet Bashir. "Darling Carlos," she replied in an affectionate note shown for the first time to Panorama. Using their childhood names for each other, the note said: "I so appreciated the contents of our telephone call this morning - it all makes complete sense to what is going on around me at this present time. 'They' underestimate the Spencer strength! Lots of luv from Duch x"

By 1995 Diana, had come to fear she had enemies in high places and was already vulnerable and unsettled. "I think that she was looking for reasons as to why things were as they were," Spencer told me.

Find out more

Watch John Ware's Panorama investigation on BBC iPlayer.

On 19 September, Spencer introduced Bashir to Diana. During this meeting, Spencer noted some 30 claims which he attributes to Bashir, including Jephson's alleged plots against her: "Jephson - dangerous: money. Left offshore a/c in March 1994".

By the end of the meeting, Spencer told me he had become highly sceptical. "I warned Diana that his stories didn't add up and apologised to her... and she said, 'Oh, don't worry, Carlos. It's nice to see you. It doesn't matter at all.' And I thought that was the last time I'd hear from or about Martin Bashir."

Bashir has claimed that most of the comments noted down by Spencer came from Diana, but Lord Dyson finds: "I am satisfied that Mr Bashir said most, if not all, of the things that are recorded in Earl Spencer's notes."

The reporter gave a very different account of his dealings with Earl Spencer - and in particular the claims attributed to him - in his evidence to Lord Dyson. He denied he had said many of the things attributed to him by Earl Spencer. Despite the findings of Lord Dyson, he still stands by his account.

For Diana that encounter was just the start of numerous meetings with Bashir. As Lord Dyson says, by late summer 1995, she was "keen on the idea of a television interview".

On 16 September 1995, Princess Diana and Prince Charles joined Prince William for his first day at Eton College

However, friends who met her in the run-up to the Panorama interview on 5 November observed a marked change. They were regarded as no longer trustworthy, including Jephson. "From Martin Bashir's perspective, I was the obstacle that had to be removed," he told me. "Because there was a fair chance that if I advised against her giving the interview to him that she wouldn't do it."

Diana's friend Rosa Monckton has written that everyone knew something was wrong "but none of us could put a finger on it".

On 30 October, the day after Diana had secretly confirmed the interview with Bashir, she met her lawyer Lord Mishcon and described to him a series of lurid plots which she said had been hatched against her.

Asked to identify her sources Diana replied only that they were "reliable" and included GCHQ.

Princess Diana photographed with her then private secretary Patrick Jephson

Is it a coincidence that among the top-level sources, Bashir would later claim to BBC management that he had met while "investigating" the dirty tricks campaign against Diana, was a member of GCHQ? It was, however, unheard of for a serving intelligence officer to disclose intercepts (even assuming that Diana's communications were being intercepted, which itself seems highly dubious) to a journalist.

The key question about the BBC for both our inquiry and Lord Dyson's was: How did Bashir's machinations elude the corporation's most senior executives, all of whom had been editors and journalists for whom the first rule is to cast a sceptical eye over anything that doesn't seem to add up?

Panorama's "An Interview with HRH The Princess of Wales" was broadcast on BBC One on Monday 20 November 1995

It was watched by 23 million UK viewers

That evening, Princess Diana was photographed at a charity event in London

Alarm bells at the BBC

The first alarm bell that should have warned BBC management something was wrong rang in December 1995, a month after the sensational interview had been broadcast. Designer Wiessler approached current affairs bosses Tim Gardam and Tim Suter and told them that he had been unwittingly drawn into forging bank statements by Bashir.

Wiessler - who says he only realised a connection between the fake documents and the interview after it was broadcast - told them he had previously approached the then Panorama editor Steve Hewlett, who had assured him there was nothing to worry about. Hewlett died of cancer in 2017, and having worked closely with him, the idea that he might have colluded with Bashir in using fake bank statements is - to me - unthinkable. And nothing I have seen suggests that Hewlett did. Nonetheless, were he alive, Lord Dyson would have sought his answer to some searching questions.

Why, for example, having been first alerted to the fake bank statements shortly after transmission, had Hewlett not reported this to management?

The evidence suggests that Hewlett first learned about the fake bank statements after Wiessler faxed them to Panorama producer Mark Killick with whom he had previously worked. Killick instantly recognised the name "Penfolds Consultants" because the company had featured in two previous Panoramas he and Bashir had made about the business affairs of former England football manager Terry Venables. Why, puzzled Killick, should Penfolds be involved with paying an ex-employee of Earl Spencer?

Killick confronted Bashir with the bank statements in the BBC canteen. The meeting was brief and acrimonious, with Bashir telling Killick it was none of his concern.

Killick, along with two colleagues - former Panorama deputy editor Harry Dean and Panorama reporter Tom Mangold - went to see Hewlett on 4 December. All three also recall the editor saying it was none of their business. Dean asked him if he knew about the bank statements, and Hewlett said he couldn't remember. But as Killick left, he suggested Hewlett talk to Spencer. Despite Spencer later calling Hewlett, we have seen no evidence that either Hewlett or anyone from BBC management did ever check Bashir's version of events against Spencer's. Lord Dyson is especially critical of this failure. He says the investigation carried out by Tony Hall and Anne Sloman, a former radio current affairs producer who later became the BBC's chief political adviser, was "flawed and woefully ineffective".

Lord Dyson said it "would have been substantially changed if they had bothered to speak to Earl Spencer".

Dean recalls that Hewlett later assured him that the information on the bank statements was true. He told Dean that Venables had given up his interest in Penfolds and the name appearing in the fake bank statements was merely coincidental. That assurance seems likely to have come from Bashir himself.

Bashir's ever-changing story

At the Panorama Christmas party, former producer Peter Molloy recalls Wiessler looking very shaken as he arrived. Wiessler told Molloy his flat had been broken into, and the only thing missing appeared to be two disks containing the bank statements. When Wiessler reported his concerns to BBC management, it became clear that Hewlett had not told his line manager Tim Gardam anything about Bashir having faked bank statements. "Tim was angry but sensible about it," recalled colleague Tim Suter in 2001. Hewlett told them there'd been "nothing underhand in getting the Diana interview".

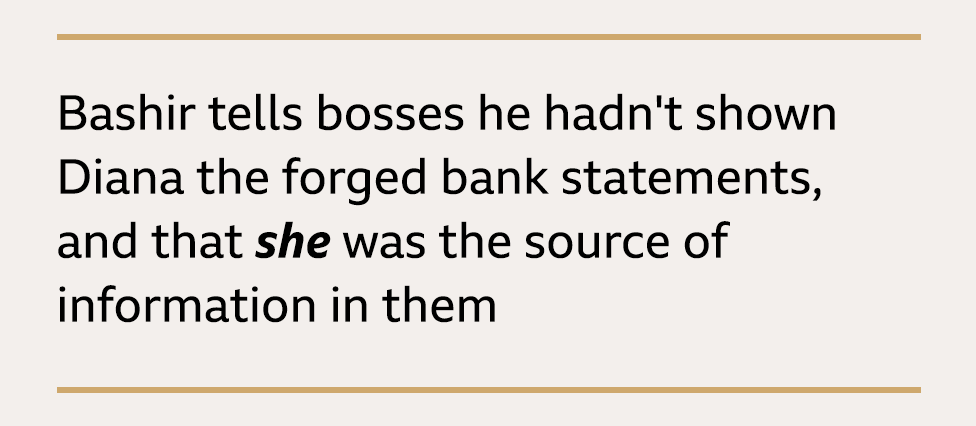

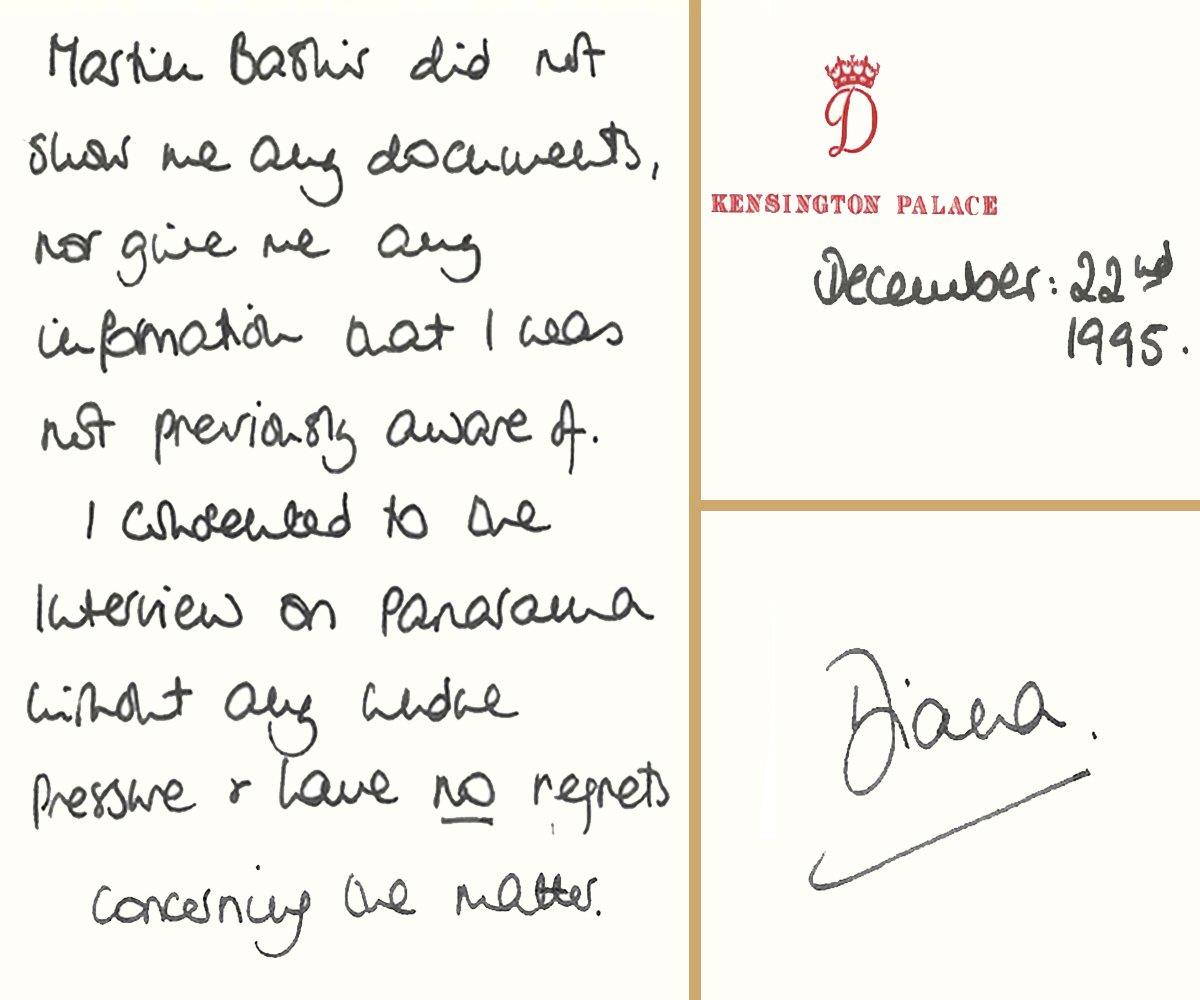

Bashir was then questioned by Gardam, Hewlett and Suter. He assured them the bank statements hadn't been shown to Diana or anyone else. They couldn't have been used to persuade the princess to give an interview, he said, because the source of the information in them had been Diana herself.

However, a note by Tim Gardam of this meeting, shows Gardam was still puzzled - why had Bashir gone to the trouble and expense of creating such authentic looking documents? He asked Bashir to seek an assurance from the Princess in writing that she'd not been shown them. The following day, a handwritten letter arrived from Kensington Palace: "I can confirm that I was not (not is underlined twice) put under any undue pressure to give my interview. I was not shown any documents nor given any information by Martin Bashir that I was not already aware of. I was perfectly happy with the interview and I stand by it."

Diana's letter put to rest any doubts management had that she'd been tricked or coerced. The BBC's greatest ever scoop, was safe. For now.

What had been missed, however, was a big clue that Bashir was lying.

Princess Diana's words to the BBC, December 1995

Bashir had already told Gardam in November that his first contact with Princess Diana had been in late September. This was mentioned in a "record of events" note by Gardam for Tony Hall. However, Gardam had also been told by Matt Wiessler that he had created the bank statements in late August/early September, some three weeks earlier.

Although both Hewlett and BBC management had been made aware of both dates, neither appear to have spotted the obvious conflict that Diana couldn't have been Bashir's source because she and Bashir were yet to be in contact. When we highlighted this discrepancy over dates to Gardam, he acknowledged he hadn't spotted it: "Had I done so, I would have questioned Martin Bashir about it." His focus, he explained, had been on Wiessler's allegation that "the documents had been shown to the Princess of Wales in order to persuade her to give an interview".

Bashir may have calculated that by naming Diana as his confidential source, BBC management would feel inhibited about checking this with her. And they never did.

He also deflected suspicion by admitting that he falsely inserted the name "Penfolds Consultants" as one of the two companies supposedly paying Spencer's ex-employee Alan Waller. His excuse? Although Diana had supposedly told him Waller was being paid by an intelligence services front company to spy on the Spencers, she hadn't known the name. All she had known, said Bashir, was that the company was based in Jersey. So he'd just inserted a dummy name because he knew Penfolds was based in Jersey.

In truth, Bashir must have realised he would never get away with passing off Penfolds as real because it had featured in his previous Panoramas. What Hewlett made of Bashir's volte-face over Penfolds given the former editor's earlier assurances to a sceptical Harry Dean is unclear. In Gardam's note of his interview with Bashir, he makes no reference to having been told about this contradiction which suggests Hewlett never told him.

Asked by Gardam why he had compiled the graphics in the first place, Bashir said it was simply to record and file the information - an implausible reason for getting a graphic designer to work all night, paying him £250 of licence fee payers' money and getting the documents couriered to Heathrow, when jotting down the details in his notebook would have sufficed.

Nonetheless, however improbable this may seem today, Diana's letter appears to have reassured management. "All could now relax for Christmas," said Suter at the time. "We had had a scare, but we had got through it." But for Earl Spencer, the letter doesn't exonerate the BBC. "Diana is dealing from a position of having been lied to. She didn't know that the whole obtaining of the interview was based on a series of falsehoods that led to her being vulnerable to this," he told me.

However, if management thought that was the end of it, they were mistaken. On 21 March, the Mail on Sunday told Spencer they were investigating how Martin Bashir had been introduced to his sister and secured his scoop interview. In order to convince Spencer of his credentials, the newspaper alleged that Bashir had shown him bogus security service documents about bugging phones at Kensington Palace. Clearly the Mail were on to something, but were wrong about the content of the documents.

Distrustful of the tabloid press, Spencer called the BBC to find out more. Spencer was put on to Hewlett and told him he had introduced Bashir to Diana "on 19 September on the back of extremely serious allegations he had made, against various newspapers, named journalists, named senior figures at St James's Palace, and unnamed figures in the secret service".

Hewlett now had a golden opportunity to question the Earl about Bashir's allegations and crucially whether he'd been shown bank statements since, unlike Spencer, Hewlett knew they were fake. It's not clear that Hewlett did ask Spencer about either point. Nonetheless, since the Mail on Sunday had mentioned forgeries, Gardam instructed Hewlett to question Bashir about this again.

Again, Bashir insisted he had not shown his forgeries to anyone, including Spencer.

On 23 March, Gardam was telephoned and doorstepped by the Mail on Sunday, so he telephoned Bashir: Had he shown the documents to Spencer? Again, Bashir denied this to both Gardam and Hewlett. Unconvinced, that afternoon, Gardam sought another assurance. Fearing imminent publication, Bashir caved in, finally admitting that he had. It had taken four attempts since December to get the truth out of Bashir.

A furious Gardam warned Bashir the BBC would have to consider its position.

The BBC investigates

Gardam was days away from leaving the BBC. He wrote a handover note setting out all of Bashir's lies. It also records Tony Hall as having agreed with Gardam that since Bashir had "misled us and… appeared to have acted unethically and in breach of the guidelines" the corporation should conduct a "full inquiry".

But what transpired could hardly be described as a "full inquiry" and was compounded by misleading statements.

The Mail on Sunday had withheld publication, but by April 1996 had firmed up their story and published Bashir's fake documents. Approved by both Hall and Hewlett, the BBC issued a statement saying the documents were "never connected in any way to the Panorama on Princess Diana". Yet by now both knew that Bashir had admitted showing the statements to Spencer. They also knew that in a written statement, Bashir had admitted showing the documents to Spencer in order to "foster" his relationship with him. Therefore the documents manifestly were "connected to the Panorama on Princess Diana".

In fact, Lord Dyson finds that the way the BBC handled its public statements as a whole in this matter "fell short of its high standards of integrity and transparency which are its hallmark".

Lord Tony Hall in 1996 and 2020

As Anne Sloman, who had taken over as Gardam's temporary replacement, and Hall carried out their "full inquiry", they never appear to have worked out that Bashir's central claim - Diana was Bashir's source for the information in the fake graphics - was a lie.

Like Gardam in December, neither Hall nor Sloman appear to have spotted that Diana couldn't have been Bashir's source because they hadn't met when Bashir commissioned Wiessler to do the graphics. But no such comparison appears to have been made. Lord Dyson does not hold BBC management culpable for not spotting the discrepancy in dates. He does, however, find that ahead of Bashir's first meeting with Diana on 19 September, it is "inconceivable" that he was "locked in a relationship" such that she would have been his source for the information in the graphics.

The Hall-Sloman investigation did draw up a chronology of events, which we've seen, but its focus was more about leaks from Panorama to newspapers than Bashir. Its chosen starting point was late October shortly before transmission, not late August/early September which is when management had already been told that Bashir had commissioned the graphics. Nor at any point did it say Bashir had lied.

The chronology reflected what Sloman appears to have thought about Panorama - "a viper's nest" seething with jealous rivalries was how she later described the atmosphere to the late Richard Lindley, himself a former Panorama reporter, for his book "Panorama: Fifty Years of Pride and Paranoia" published in 2002. "All felt they had a God given right to leak to the press" said Sloman.

Earl Spencer and his wife, Karen, at the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, May 2018

Had Earl Spencer spoken out, his notes would have blown apart Bashir's story - and the BBC would have been confronted with one of its biggest crises. However, Spencer told me the reason he didn't was because he didn't know the BBC had launched an inquiry and Princess Diana's Panorama interview was "seen as very controversial. And if I had gone against it while she was alive, then I didn't want to be seen to be undermining her in any way."

Moreover, at the time, Spencer didn't know the information in the bank accounts was entirely fake, or that Bashir had told the BBC his sister was the source.

Also, the Mail on Sunday revelation quite quickly ceased to have traction. BBC press briefings that "jealous colleagues" were behind the paper's story had distracted from its allegation about Bashir's subterfuge, Spencer wasn't talking, and management hoped he never would. "The Diana story is now dead, unless Spencer talks. There's no indication that he will," wrote Anne Sloman in an internal BBC management document a fortnight after the Mail on Sunday story.

Bashir had already put Diana off limits for questioning by claiming her as his source for the "exact" payment sums to her brother's former head of security Alan Waller. Now in conversations with management, Bashir did the same to her brother claiming it was Earl Spencer himself who was his source for Waller's bank account details - something he'd not previously mentioned.

Bashir had changed his story again but it seems not to have rung any alarm bells. Spencer only learned last autumn that Bashir had accused him of misusing private information and categorically denies there is any truth to it. In anger he contacted the BBC urging they hold an independent inquiry - hence Lord Dyson.

"In a credibility contest between Earl Spencer and Mr Bashir, Earl Spencer wins convincingly," says the former Supreme Court judge.

In Lindley's history of Panorama, Anne Sloman is quoted as saying Bashir was interviewed by Hall "at length", with Hall at one end of her "grand desk" in Broadcasting House, Bashir at the other. "Certainly, Bashir had forged these documents. It was a stupid thing to do - it didn't get him the interview. Why he did it, God only knows."

To those of a more curious disposition, the circumstantial evidence pointed in only one direction: that these documents were Bashir's way of getting his foot in the door of the Spencer family. That is also the finding of Lord Dyson, who says: "I conclude that Mr Bashir showed the fake statements to Earl Spencer before there was any contact between Princess Diana and himself."

BBC's former chief political advisor, Anne Sloman, photographed in 2003

On 25 April 1996, Hall reported the results of his "personal investigation" into Bashir to the BBC's governors, at the time the body appointed to regulate the corporation. A statement written by Hall for the governors' meeting quotes him as saying that Bashir's explanation for having commissioned the graphics was simply because "he wasn't thinking". Then came Hall's exoneration: "I believe he is, even with this lapse, an honest and honourable man. He is contrite."

Hall's statement made no mention of what he already knew by that point, that Bashir had shown the fake documents to Spencer and had repeatedly lied to his editor and to senior management. At the same time, Hall refers to "TRUST" (which Hall spelled out in capital letters) and "straight dealing" as "paramount" BBC values.

While Hall's statement to the governors criticised Bashir for having been "incautious and unwise", he assured his fellow managers he was "certain there had been no question of Bashir trying to mislead or do anything improper with the document" - implying nothing improper had taken place.

Lord Dyson comments: "To dismiss his actions as no more than a mistake, unwise and foolish did not do justice to the seriousness of what he had done."

An internal document faxed three days before the board of governors meeting shows that management seem to have privately acknowledged Bashir had been in breach of journalistic ethics and BBC rules: "Management will have to decide what action if any to take privately or publicly about Bashir, what to do about his contract and how long he should stay on Panorama."

Lord Hall told Panorama Bashir was given a "severe reprimand" and was placed under "close supervision". It is true on 4 April 1996, Tim Suter wrote a letter addressed to Bashir saying the creation of the graphics "was in breach of BBC's guidelines on straight dealing… compounded by your failure to inform the head of department of the use made of this material when directly questioned by him. You should be in no doubt of the seriousness with which we view this nor of the reprimand that this letter represents."

Lord Dyson in 2015

However, Lord Dyson finds that the letter was probably not sent to Bashir and further, that there is no record of a reprimand on his employment records. Panorama's then deputy editor Clive Edwards told me he was "unaware of any supervisory order on Martin".

"It is difficult to imagine how any such order could have been in force but not known to me as deputy editor, since I would have been the person to supervise such an order."

Bashir remained with the BBC until 1998, when he left to join ITV.

The 'entire truth'

The most senior managers responsible for BBC journalism appear to have swallowed a whale of a story, and in a 2005 interview for the BBC's Arena documentary series to celebrate the scoop's 10-year anniversary, Tony Hall unwittingly explained why: "Martin is the sort of interviewer who works very hard at getting into your confidence."

It seems to have worked on everyone - despite Tim Gardam's parting note to his management colleagues emphasising the need for the BBC to get to "the entire" truth of what Bashir had been up to.

For the anonymous BBC leakers without whom we would never have known about Bashir's dishonesty there was only excoriation - briefed against by the BBC to the newspapers as "jealous colleagues" and referred to in an internal management document as "troublemakers." Because of "this sordid saga", says the document "we can either go the formal disciplinary route, which needs proof and may be messy or pick off the troublemakers one by one with a stiff warning and ensure they are found work elsewhere as speedily as is practicable".

The only named whistleblower Matt Wiessler would never again get any BBC work, Hall assured the governors. Wiessler paid a heavy price - his freelance graphics business eventually collapsed so he left London and in his own words became "a bit of a drifter… I tried lots of other things, but at heart I was always a television current affairs guy. Hall called Martin, a 'good and honourable man'. I want him to reverse that because I'm the good and honourable man in this."

In response to Dyson, the BBC offered a "full and unconditional apology" and said it would be writing to "a number of individuals involved".

Wiessler says the least the BBC could do is include him in that list.

Princess Diana visited Argentina, shortly after the BBC interview was broadcast

In overall charge of the BBC at the time was director general John Birt. He says the revelation that the BBC "harboured a rogue reporter on Panorama who fabricated an elaborate, detailed but wholly false account of his dealings with Earl Spencer and Princess Diana" is a "shocking blot on the BBC's enduring commitment to honest journalism; and it is a matter of the greatest regret that it has taken 25 years for the full truth to emerge. As the director general at the time, I offer my deep apologies to Earl Spencer and to all others affected."

Lord Dyson has little to say about how BBC governance was undermined by Hall's "woefully ineffective" investigation.

Our own investigation sheds some light on this, however.

Lindley's book on 50 years of Panorama quotes Sloman as saying that she, Hall and Birt had a 90-minute meeting about Bashir but it doesn't go into detail as to what transpired. Lindley's widow let me search her attic for his original notes. I found that Sloman told Lindley: "We concluded that faking documents had been going on as a general practice" and that "our business creates monsters… never did Birt express interest in covering his own back… Birt wanted to get to the bottom of the matter."

I understand Birt has no recollection of any such meeting, but that he thinks his reference to wanting to "get to the bottom of the matter" refers to a meeting immediately after the Mail on Sunday revelations. What briefing Birt may have been given on the results of Hall's investigation before the boards of governors and boards of management is unclear, except that Birt is said not to have been told that Bashir had repeatedly lied. In fact, no evidence of Bashir having lied is mentioned in any of the documents written by Hall or Sloman that have surfaced.

However, Lord Hall told Panorama that he was "open and transparent with the director general and with colleagues on the board of management and I believe I gave them all the key facts... throughout I discharged my responsibilities in good faith". For his part, Lord Dyson finds that Hall "presented these facts to both the board of management and the board of governors as if they were uncontroversial".

Lord Dyson continues: "And yet he knew (but did not tell the board) that they derived from Mr Bashir's uncorroborated version of the facts and that Mr Bashir had lied on three occasions on a matter of considerable importance."

In a statement, Lord Hall said: "I accept that our investigation 25 years ago into how Panorama secured the interview with Princess Diana fell well short of what was required. In hindsight, there were further steps we could and should have taken following complaints about Martin Bashir's conduct."

He said he was "wrong" to give Martin Bashir the "benefit of doubt, basing that judgement as I did on what appeared to be deep remorse on his part".

Martin Bashir said in a statement that he had apologised then, and did so again now for asking for bank statements to be "mocked up".

But he reiterated that "the bank statements had no bearing whatsoever on the personal choice by Princess Diana to take part in the interview".

He said Lord Dyson had accepted that the princess would "probably have agreed to be interviewed without what he describes as my 'intervention'".

And he said he was "immensely proud" of the interview, in which Princess Diana "courageously" talked through the difficulties she faced. He said in it, she "helped address the silence and stigma that surrounded mental health issues all those years ago. She led the way in addressing so many of these issues."

The least that can be said is that Bashir tried to con everyone. Others may say Bashir told management what they too readily wanted to hear - to spare the corporation the ignominy of undermining a truly global scoop. In 2016, Bashir was rehired by the BBC as religious affairs correspondent. The announcement referred to his "track record in enterprising journalism" and previous experience on "BBC religion and ethics programmes."

He resigned as the BBC's editor of religion before the publication of the Dyson report.

Managing relationships 'cleverly'

The last word must go to Panorama's editor at the time, Steve Hewlett. He too was interviewed for the BBC Arena documentary marking the 10th anniversary of Bashir's scoop. I understand Hewlett agreed to be interviewed provided he wasn't asked specifically about the forged bank statements. Instead, he was asked how Bashir met Diana.

Arena didn't broadcast his answer and the BBC refused to release it to us. However, we obtained a transcript which shows the normally sure-footed Hewlett seeming to stumble: "I'm sure he told me he was going to see her… look, he's a journalist, he does his business, I don't follow him around all day, so you know, I've got a show to run… what, precisely… how he did it, to be honest I don't know."

If this was Hewlett's way of saying he hadn't known all the strokes Bashir had pulled before transmission, that is very likely to be true. I and others knew Hewlett to be an ethical journalist.

He continued: "You know… he's an operator, so he manages relationships very cleverly. I don't mean…dishonestly, but he manages them cleverly."

Steve Hewlett in 2016

Was Hewlett really still convinced by 2005 that Bashir had "managed" his relationship with Diana "very cleverly" but not "dishonestly"?

The idea that Hewlett hadn't yet suspected that Bashir got to Diana by deceiving Spencer sits uneasily with his careful editorial eye.

Yet, however Bashir got his scoop, it was undeniably real and Princess Diana was, by several accounts, intent on telling her side in the War of the Waleses. At the same time, the reporter to whom Hewlett had entrusted this assignment turned out to be "rogue" confronting him with an acute dilemma. Did Hewlett reconcile this by deciding the authenticity of the scoop trumped an otherwise tainted process? I pose this as a question, not an allegation, because Hewlett is no longer here to answer for himself. Yet it seems he was troubled by something.

It is 2004, a late-night bar in Sydney. By chance Hewlett has bumped into a colleague Phil Craig, who had just produced a documentary about Princess Diana. They talk and they drink. Having previously worked on Panorama, Craig knew a little of the rumours. "We were coming at this from different sides," he recalls "so with Steve there was a sense of 'let's talk it all through'. I came away that night with the very strong impression that he thought there was a chance that one day the Bashir story would cause everybody a lot more trouble, that there was more to come out about the background to the interview, that there was something that hadn't gone away and was still lurking in the shadows."

That "something" turns out to be a timebomb about public trust that the BBC tried to defuse 25 years ago, but left it ticking. That bomb has now detonated.