Turkey's plastics ban: Where does the UK send its waste now?

- Published

The boy was probably only a teenager. Rummaging through bags of plastic dumped by the side of the road, he was looking for bottles to sell.

In amongst the rubbish, were plastic bags from some of the UK's biggest supermarkets, packaging for cheese, ham and beef burgers.

Our investigation in March 2020 in the southern Turkish City of Adana found that although plastic that had been carefully sorted and separated by households in the UK was being sent to Turkey for recycling, it was, instead, being fly tipped and burned.

Now Ankara has had enough - from today, 2 July, almost all imports of plastic waste are expected to be banned.

This leaves the UK with a real problem.

In Turkey, a boy searches through bags of plastic to find bottles to sell

Last year the UK sent more plastic packaging waste to Turkey than to any other country. More than 200,000 tonnes, or 30% of all such exports, according to the Environment Agency's national waste packaging database.

This means 30 shipping containers a day full of plastic waste now need a new home. The UK, however, doesn't have enough recycling capacity to handle it itself.

"The alternatives are not obvious," says Phil Conran from consultancy 360 Environmental.

China, which used to be the world's biggest importer of plastic, closed its doors in 2017. And Malaysia, traditionally another major recipient, is now more heavily regulated.

Angus Crawford looking through plastic waste found dumped on roadsides in Turkey last year

Phil Conran points out that the "UK has an unfortunate history of poor quality plastic waste exports".

Simon Ellin from the Recycling Association says most exports are compliant but admits, "Our industry is blighted by a small minority of illegal operators who take advantage of an under-resourced UK regulatory system and the lack of transparent export systems."

Eastern Europe options

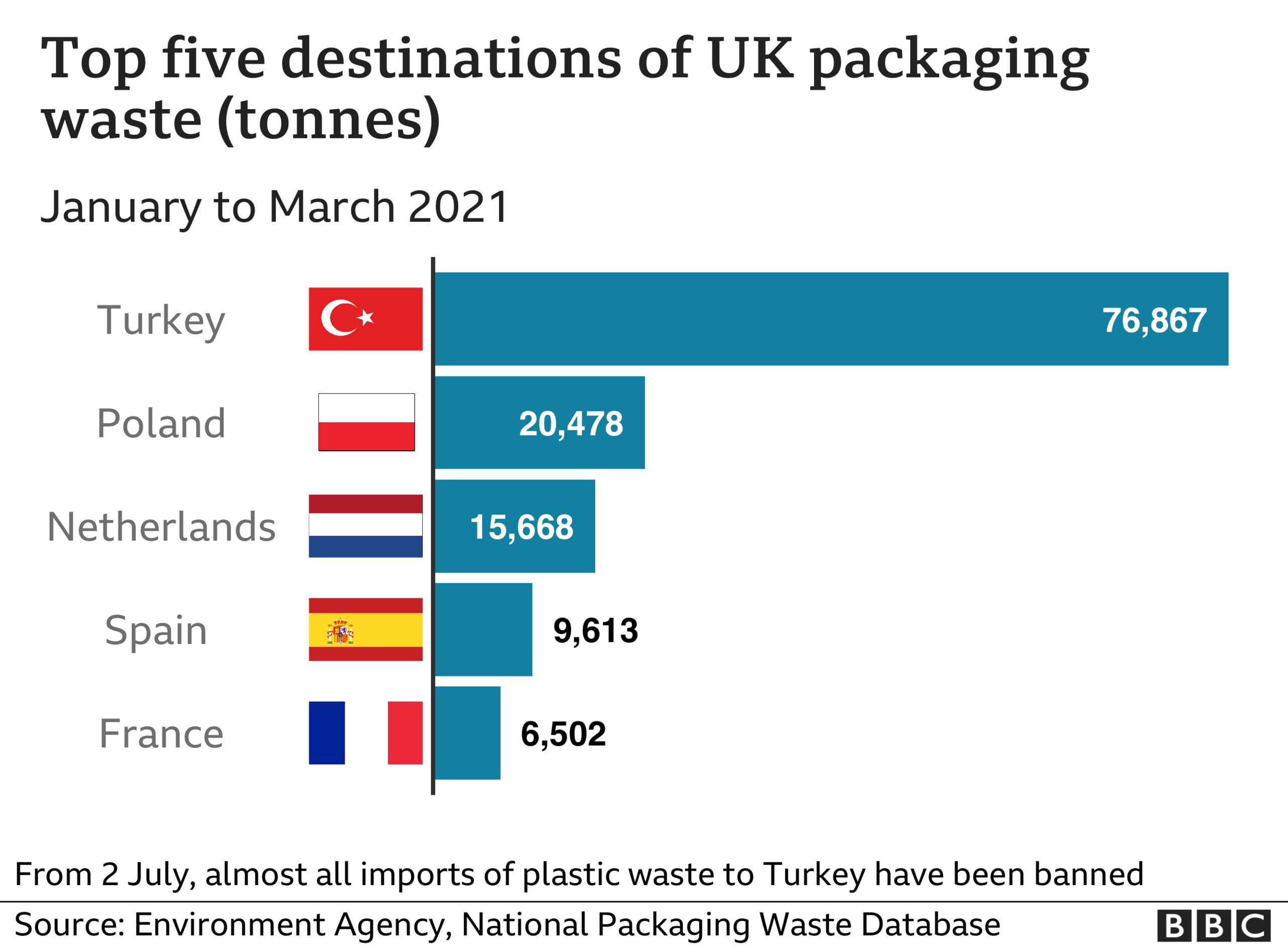

In the first three months of this year Turkey took 49% of all exports - Poland was second and Holland third. But those two countries would have to more than double their imports to make up the difference.

And some UK waste sent to the Netherlands is actually incinerated and an import tax on waste for burning now makes that less appealing.

Other countries in Eastern Europe might also be preparing to receive UK material, but domestic recycling rates there remain low.

"The UK government may try to keep pushing our plastic problem onto other countries in the short-term, but the writing is on the wall for waste exports," says Megan Randles, political campaigner for Greenpeace UK.

The government believes plastic waste can legally and safely be sent abroad for recycling. But a spokesman for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) said: "The UK must handle more of its waste at home, and that's why we are committed to banning the export of plastic waste to non-OECD countries and clamping down on illegal waste exports."

The Environment Agency says in the past 18 months it's stopped 160 containers of illegal plastic waste leaving the country.

Plastics backlog

So if more of our plastic stays in the UK, what's going to happen to it?

The UK's recycling capacity is still only 75% of what was being sent to Turkey. So in the short term, a build-up of waste is likely.

Phil Conran says that's not without its problems.

"Excessive stocks can lead ultimately to material being landfilled or abandoned if the expected markets don't materialise."

But there is a third possibility and that's incineration - including in energy-from-waste plants. In this process, energy is recovered in the form of heat or electricity.

More than 40% of household waste in England is currently burned - of that about 8% is made up of plastic.

Simon Ellin from the Recycling Association says its a short-term solution. "Some materials will need to move down the waste hierarchy and be burnt with the energy recovered for electricity generation."

Greenpeace's Megan Randles doesn't agree. "We can't dump or burn our way out of our plastics crisis. We need a legally binding reduction in the production of single use plastic"

The Turkey ban could lead to more recycling in the UK. Currently, Defra estimates that 46% of plastic waste is recovered or recycled.

The government is planning a new recycling levy on plastic producers and wants all packaging to be made of at least 30% recycled material by 2022.

The recycling industry is expanding capacity. Construction of what the developer describes as the UK's first plastic-to-hydrogen plant is expected to begin this year in Cheshire, and plans have been unveiled for similar plants across the nation.

Also later this year, one of the biggest waste facilities in the country will become fully operational in Avonmouth near Bristol.

It will burn non-recyclable household waste to fuel a plastics recycling plant, and in its first year it's expected to take 1.6 billion bottles, pots, tubs and trays.

But in the short term there is a fear that what the BBC found in Turkey may simply be duplicated somewhere else. That could be in Eastern Europe, or Africa - or it could be in our own back yards.