Zoomtown-on-Sea? The lure of a new life on the coast

- Published

It was three in the morning when Sam Lancaster found her family's new Yorkshire home by the sea.

"I don't even know what brought Scarborough into my head. I just googled it," she says.

It was house-love at first sight. But there was another key piece of information. Her husband Craig had been told by his employer, a major telecoms firm, that he could work - indefinitely - from home. Sam and Craig and their two daughters really could live anywhere - including the seaside.

The Lancasters say they had "outgrown" their home in Thatcham, Berkshire, not far from Craig's office in Newbury. And no longer constrained by the geography of a daily commute, they started looking for better value houses in other parts of the country.

Now they're unpacking boxes in a big, rambling home on the North Yorkshire coast, with the sea a blue horizon out the back window. In this week's picture-postcard sunshine, they've been swimming in the sea most days.

"It's a no-brainer. It feels so right," says 41-year-old Sam, convinced her family's migration 230 miles north, as the gull flies, is going to be part of a bigger trend. "If you can work from home, why wouldn't you move?" she says, swatting away any doubts.

Craig, whose IT job supports network operations, says a trip to Screwfix turned into a nature trek. "We saw seals swimming in the sea and puffins. You wouldn't see that in Thatcham."

"Just look out the window. There are lovely walks, people have been welcoming, the girls can go down to the beach," says Sam. She's in a mover's honeymoon where everything still feels like a holiday, even though she says some of the locals are more likely to "slag off the town".

Some of their old friends also thought they were crazy for uprooting. Sam says they quietly asked her whether she thought it was a rash decision.

But there was another piece of rocket fuel for this life change.

The awfulness of the pandemic made her think there was no point in hesitating. She had "gone off" their old area. Here was a chance to reinvent their lives. "I would never have done this without the pandemic," she says. She worked as a teaching assistant before and might return to that later. But nothing was going to hold her back.

It will mean new schools for Sophie aged 15, and Olivia, eight, and making new friends for parents and children. But they seem unfazed and confident about a fresh start.

"Life is so short," says Sam.

The Lancasters could be part of a changing tide. The big beaches and widescreen skies have always made seaside towns seductive, but they can be slow to reach. Coastal transport can have more dodgy links than a crazy golf course. Will remote working make the coast a practical option? Will people start moving to Zoomtown-on-Sea? And could this revitalise fading seaside towns?

Figures up to June 2021 from the Rightmove property network showed a 115% increase in enquiries about moving from cities to a seaside town, compared with before the pandemic.

These are people viewing properties and getting information, not completing sales. But Tim Bannister, director of property data, says: "It's a really strong indicator, a window into what's happening."

There has also been a shift from most city dwellers looking to move. Before the pandemic they were looking for properties in the same city. Now, most are looking elsewhere. It's an out-of-city trend that applies to London, Birmingham, Bristol, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester. The rise of hybrid working is a big factor, according to estate agents.

"People are reassessing their lives," says Phil Fletcher, of CPH estate agents in Scarborough. He also wants the town to reassess its relationship with seagulls, which have just caused a leak in his ceiling.

He says people who have had tough experiences in the pandemic are now making big choices about their relationships, their jobs and where they live.

"People are sitting up and thinking: 'Live for the day.'"

Coastal towns, like sea views, are always changing. Where his estate agency now stands was the site of the Theatre Royal, when Scarborough was an entertainment capital. The idea of remote workers moving to cheaper, characterful Victorian houses in Scarborough is not future-gazing for him: "I can see it already happening."

But seaside towns can have a Jekyll and Hyde character.

On a sunny day Scarborough looks irresistible. Families are outside ice-cream coloured chalets, one with a placard saying: "Be Nice or Go Home." Boats are running trips to see dolphins off the coast. Holidaymakers are shielding their chips from dive-bombing seagulls.

It's not just the memorial plaques on seafront benches that prove how much people love to sit and look at the sea.

Environmental psychologist Michelle Tester-Jones, at the University of Exeter, is part of a research project which has found "consistent evidence that spending time near 'blue spaces' seems to be good for well-being", including helping with "anxiety and low mood".

But take a short walk from Scarborough's seafront and there are boarded up shops on the High Street, like teeth missing in a smile. The Christmas bargain store is still promising presents in July. A food bank collection point stands in the locked-up entrance to Debenhams. The town has immense natural beauty and handsome old buildings, but deprivation - in income, health and education - runs through Scarborough like a stick of rock. It's a low-income economy with many jobs relying on summer tourism. Male life expectancy has been going into reverse.

"It's a town of two cities - of bizarre contrasts," says Andrew Clay, director of Scarborough Museums Trust.

"We have wealth and successful businesses," with a legacy of great architecture and spectacular views, he says. "But some of the areas here are some of the UK's most depressed - in terms of social deprivation, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, hard-to-reach communities. There's an issue with aspiration in the town," he says.

This mix of light and shade has always been there, perhaps. Mr Clay is speaking in a wood-panelled room in what was once the home of the aristocratic Sitwell family. Edward VII stayed a couple of doors down, when Scarborough was a royal playground. Until he caught typhoid.

The wheel will turn again, and Scarborough will find new ways to appeal to a wider and wealthier range of people, says Mr Clay. That's if it upgrades its facilities, like getting a multiplex cinema and making better use of its cultural heritage.

"It's a town that has always reinvented itself," he says.

I have a nephew who has just started a job remotely - he would never have applied before because it's based in London

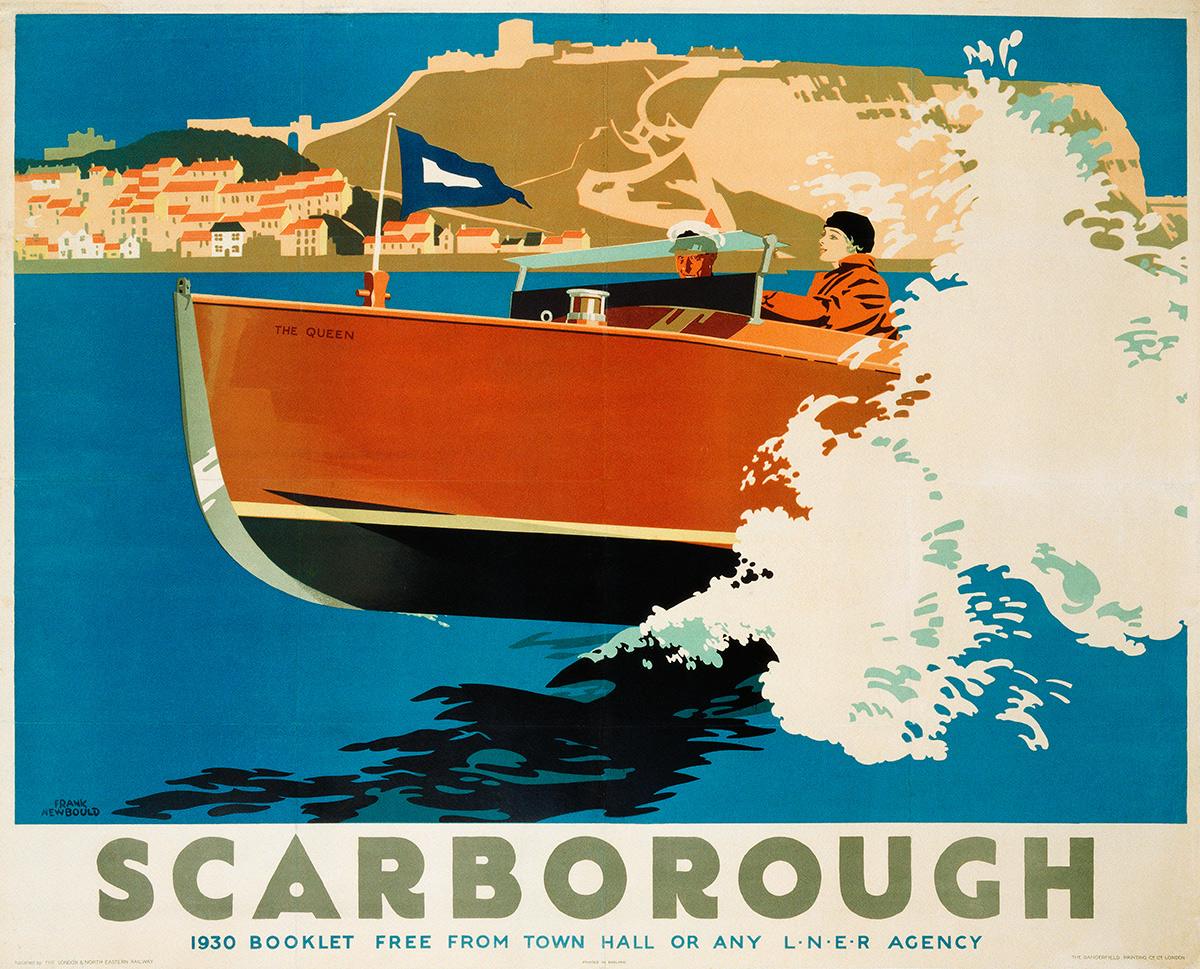

Seaside towns can be like those distorting mirrors in funfairs. Posters of Scarborough from the 1920s and 1930s show glamorous couples in sleek cars and speed boats, with the bays and sandy beaches looking like the south of France. What you see depends on your perspective.

Liz Colling, Scarborough's councillor in charge of inclusive growth, wants the town's next reinvention to be about revitalising the local economy, including encouraging more digital jobs. It's a "very realistic ambition" which is already beginning to happen, she says. "I have a nephew who has just started a job remotely. He would never have applied before because it's based in London," says Cllr Colling, adding that her son is also working remotely.

"Historically our younger people have left town to pursue education and jobs, but this is a sign that you can still stay here and have a really good career," she says.

Local digital marketing firm, Digital Zest, has had a boom time during the lockdown, with so much going online. Managing director Paul Taylor expects more people to come and work remotely, because of the quality of life and being able to go straight from desk to beach. But even the digital world needs to travel - and he wants improvements to road and transport connections.

How Scarborough appealed to upmarket tourists in 1930

Scarborough, one of the "left-behind towns", is getting more than £20m "levelling-up" funding. But it raises the question of what such labels mean, because the town has little of the graffiti, grime or street-begging in a "richer" place such as London.

The real difference is in the jobs market - and it's why the arrival of Zoom workers is significant. It's a town with very few professional jobs. It has half the average for the Yorkshire and Humber region, and below a third of a resort such as Brighton. For civil service jobs, Scarborough has only a fifth of the national average.

It also struggles to attract people to stay in such professional jobs - for instance the town has been blighted with problems in recruiting NHS dentists. Parents have had to take their children to other towns to find a dentist.

Timo Hannay, a data analyst who has researched the struggles of coastal communities, external and who advises policymakers, says Scarborough has many of the problems typical of seaside towns - but to a slightly greater degree. We'll keep being fascinated by these towns, he says, because the seaside carries such a strong sense of Britain's changing identity - both in its "self-assurance and self-doubt".

What can get overlooked about Zoom-working is the long-term change for remote workers themselves.

Craig Lancaster is 52. He could spend the rest of his working life alone at home with his multiple computer screens. "I do miss the interaction, that's the one thing work-wise. I don't think it's as personable as being in the office face-to-face," he says. No-one else at home will want to obsess about office politics, there are no workmates to meet over coffee.

But for Craig, the positives of a better work-life balance outweigh any drawbacks.

"Work is changing. Productivity has gone up with people working from home. Businesses have realised that trusting their employees means they're saving money, they're not having to pay for buildings."

Seaside towns have often been defined by what they used to be. In Scarborough you can almost hear the ghosts of old comedians and imagine the big summer crowds filling huge Victorian hotels, which have become cliff faces for nesting seagulls.

Could it be that the unexpected opportunities afforded by the pandemic will see flocks of a different sort descend on the town?

In a series of special reports BBC News has been looking at the challenges and opportunities in seaside towns such as Scarborough.

Photography by Ceri Oakes