Levelling up: The seaside town fighting violence and frustration

- Published

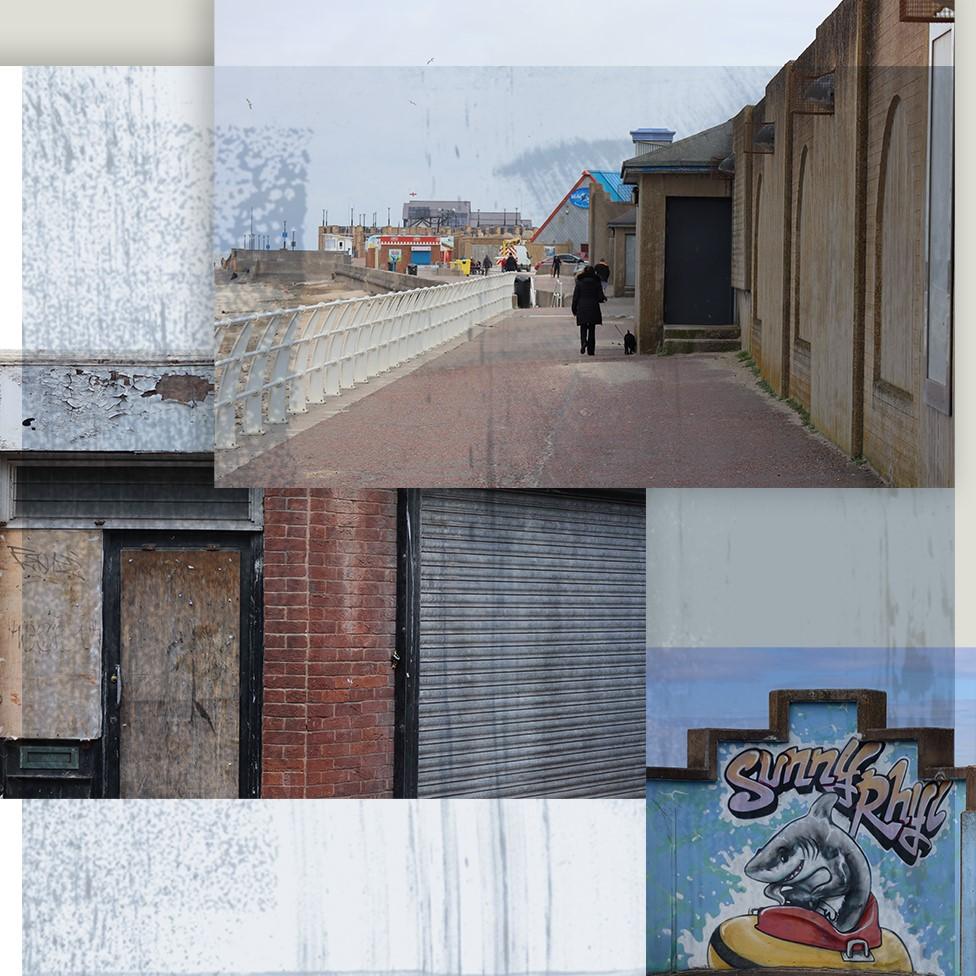

The north Wales seaside town of Rhyl is one of the most violent and deprived areas in England and Wales. The number of serious offences went up every year for four years until the first coronavirus lockdown, BBC research has found.

One of Boris Johnson's key policies when he was elected prime minister was to end the deep-rooted inequalities between richer and poorer parts of the country, starting with crime - and nowhere is that challenge clearer than in Rhyl.

In the first of a series of reports tracking the progress of the government's "levelling up" agenda, BBC News looks at how one town is trying to change.

It's a summer evening and people are standing outside pubs, enjoying the weather, drinking with friends.

A group of partygoers from Yorkshire amble by in fancy dress. Batman nips into a kebab shop on Water Street, while the Joker and the Penguin wait outside.

Minutes later officers try to reason with a couple being barred entry to a pub. They have their work cut out.

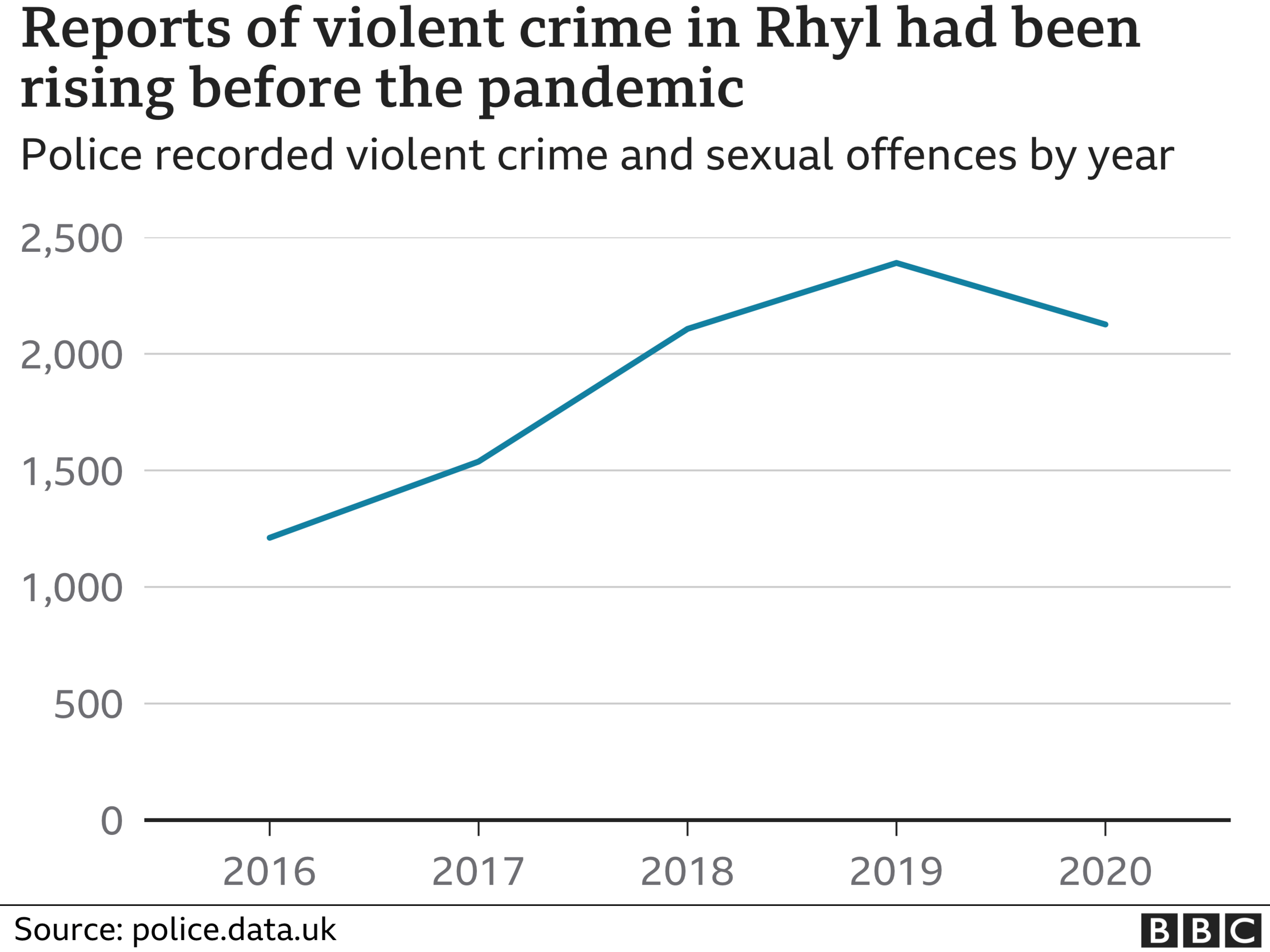

In Rhyl, violent crime and sexual offences rose every year from 2016, according to BBC analysis of police data.

The trend only stopped during recent lockdowns, which saw dramatic falls in crime across the UK as the night-time economy shut down.

Not all forces are as rigorous as North Wales Police in recording crime but that should not disguise the worrying upward trajectory.

Now, pubs in Wales are serving again, nightclubs will reopen on 7 August and the police are nervous.

"I think Rhyl is at a bit of a crossroads at the moment," says Insp Jason Davies.

He grew up in the town and has recently returned as its most senior officer.

"I knew I was going to have to roll my sleeves up here... but it's something that I'm personally vested in and passionate to improve the situation."

Occasionally interrupted by humorous interjections from drunk passers-by, Insp Davies explains how, in his time away, violence has become less about street brawls after kicking-out time.

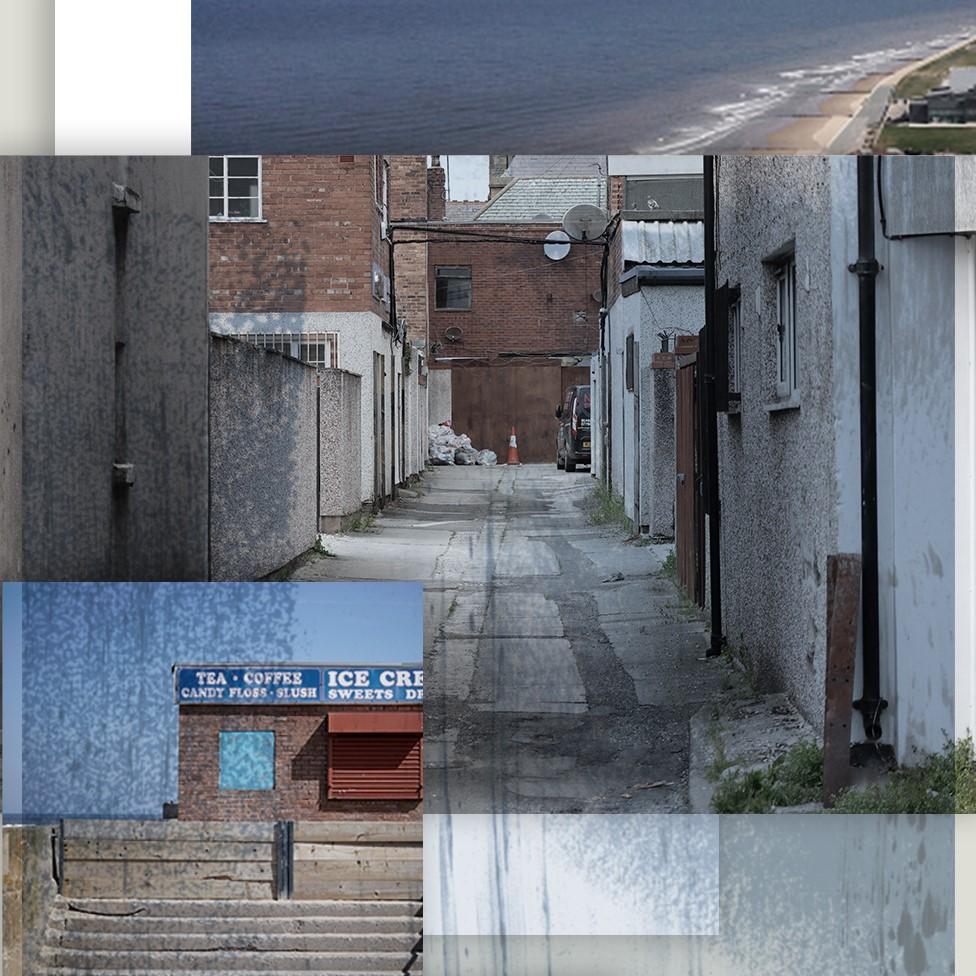

Organised crime gangs, usually from nearby Liverpool, run County Lines drugs through Rhyl and as soon as officers close down one line, another pops up.

"They tend to prey on what they see as the vulnerable," says Insp Davies. But he believes flooding the area with extra officers is not the answer.

"A lot of the families who live in west Rhyl have generational issues with some things like alcoholism, drug misuse, poor mental health, a lot of that is tied to the social deprivation issues that we have in the town… those are the root causes behind the violence."

Some of the people we met in Rhyl had never heard of levelling up but Insp Davies is clear it should mean investing money "to tackle the underlying causes of crime".

'He would have killed me'

Across town, Natasha Harper is fielding calls at the Good News Mission, a thriving community hub in a former church.

Almost 100 local families turned to the food bank each week during the pandemic and there has been no real let-up since.

Desperate circumstances are fuelling another huge crime problem in Rhyl - domestic violence.

People don't feel like they can go to the police. They are too frightened and worried their children will be taken off them.

"It's been quite traumatic these last few months listening to people's stories," says Natasha.

Some "need £300 a day for a family member to continue their habit and they haven't got it. Tensions are high and their partners take it out on them."

The violence often goes unreported, she says, because people "don't feel like they can go to the police".

"They are too frightened and worried their children will be taken off them."

Natasha, a furloughed outreach worker who has lived in Rhyl for more than 20 years, has first-hand experience, having been attacked frequently by an ex-partner who was addicted to alcohol.

"There were beatings, theft of jewellery to sell for drink, lots of emotional abuse, broken bones, cuts," she says.

And once, when she was cornered in the kitchen: "He was standing over me with a chair and I knew that if I couldn't get away he would have killed me.

"I managed to bite his arm so I knew I had to call the police."

Natasha ended the relationship and now focuses on helping others. "There's a lot of worried people out there," she says.

"Crime just gives the place a bad name," sighs Hugh Evans, leader of Denbighshire County Council.

"That's probably been one of the key barriers we have had to address in terms of getting the private sector and getting confidence in the town of Rhyl.

"We forgot about Rhyl at a crucial time, late 80's, early 90's," he says.

He regards it as a collective failure by local and national leaders but points to millions of pounds of investment by the council, the Welsh government and the EU in recent years, especially along the seafront, and believes levelling up money from the UK government will also help.

'Bottled up frustration'

"After the first lockdown we observed a spike in both violent and acquisitive crime in areas of high poverty," says Prof Tom Kirchmaier from the London School of Economics.

Prof Kirchmaier and colleagues at the LSE's policing and crime research group helped the BBC collect data identifying areas across England and Wales with high rates of violent crime.

He fears another increase in the short term.

"There is a lot of bottled up frustration especially in poor areas so you will see a lot of aggression and disorder."

The work of the police is not futile, he says but "domestic abuse will need to be tackled fundamentally differently to county lines".

And he cautions: "The bobby on the beat, while being the public's favourite crime solution, will also be the least likely to actually be successful."

'Saving our community'

Down a decaying backstreet, students at John Lynn's Black Belt Karate Academy are training in self-defence, perfecting a highly choreographed move called the kata.

Black belt Ioan Beating, 16, explains how he often hears about "drug selling, sometimes stabbings" in Rhyl, prompting concerns "for my friends' safety and everyone else's safety".

His teacher, John Lynn was converted to karate after watching Bruce Lee films nearly 40 years ago and today uses it to "get the youngsters off the street".

"We stop them from having peer pressure, we give them confidence so they can say no to drugs and we try to teach them to be respectful and disciplined," he says.

Mr Lynn, is proud of the hundreds of teenagers he has helped train in Rhyl over decades.

He hopes levelling up will drive out the drug gangs but, in the meantime, says: "We are doing our little bit".

"We're trying to save our community one student at a time."

Additional reporting by Michael Buchanan.