Afghanistan: How can the West stop terror bases?

- Published

The West has, until now, had help from Afghan special forces in operations against insurgent groups in the country

"The UK will fight Islamic State by all means available," says Dominic Raab. The foreign secretary added that the UK would "draw on all elements of national power" to pursue the group's leaders.

So what does that mean in practice? What exactly are the tools at Britain's disposal? Or is this, as some critics would maintain, just an empty boast?

After Western defence and intelligence agencies collectively failed to foresee the speed at which Afghan National Security Forces would collapse, it seems they have since lost no time in making discreet approaches to the incoming Taliban government.

In a surprising move, the CIA Director, William Burns, reportedly flew to Kabul almost within hours of the Taliban takeover of that city, holding talks with their political chief, Mullah Baradar.

A key aim is to stop Afghanistan becoming a haven for transnational terrorism. The former chief of MI6, Sir Alex Younger, told the BBC: "I am not optimistic that the Taliban have the capability to do this, even if they had the intent."

He added: "It will be important... to persuade neighbouring states that, for all our differences, we actually have the same problem and need to find some form of co-operation."

Pakistan plays a crucial role in achieving this goal, and Richard Moore, the current chief of MI6, has held talks with its army chief to discuss just that. Pakistan's shadowy Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) have supported numerous militant Islamist groups in the region. Yet at the same time, Pakistan has suffered multiple casualties from domestic jihadist terrorism.

Intelligence officers from MI6 are also reported to have held talks with the Taliban in both Kabul and Doha with the simple message that if a Taliban-ruled Afghanistan is to have global legitimacy, then it cannot be allowed to again become a haven for terrorism.

MI6 talking to the Taliban is not new. What is new is that the entire paradigm of US-backed counter-terrorism in Afghanistan changed at a stroke on the day the Taliban walked into Kabul on August 15th.

The Taliban takeover of nearly the whole of Afghanistan means that the West - and specifically the CIA, MI6 and other intelligence agencies - no longer has a trusted, in-country security service or Afghan special forces to work with.

For the nearly 20 years that Nato and other multinational forces have been in Afghanistan, the intelligence provided by the country's National Directorate of Security has been vital in disclosing the covert activities of al-Qaeda, ISIS-K (the Afghan affiliate of Islamic State group) and other jihadist militant groups.

Afghan, US, British and other special forces were then able to swoop in, often by helicopter in the dead of night, and close down those bases before they could successfully launch any international attacks.

Hence the claim that for 20 years there has not been a single transnational attack launched from Afghanistan while Western forces were there.

So what now? What's left?

The loss of both its Afghan bases and an established network of human informants has forced the West - primarily the US and UK - to now rely on two other methods: cyber interception of messages, and "over-the-horizon" drone strikes.

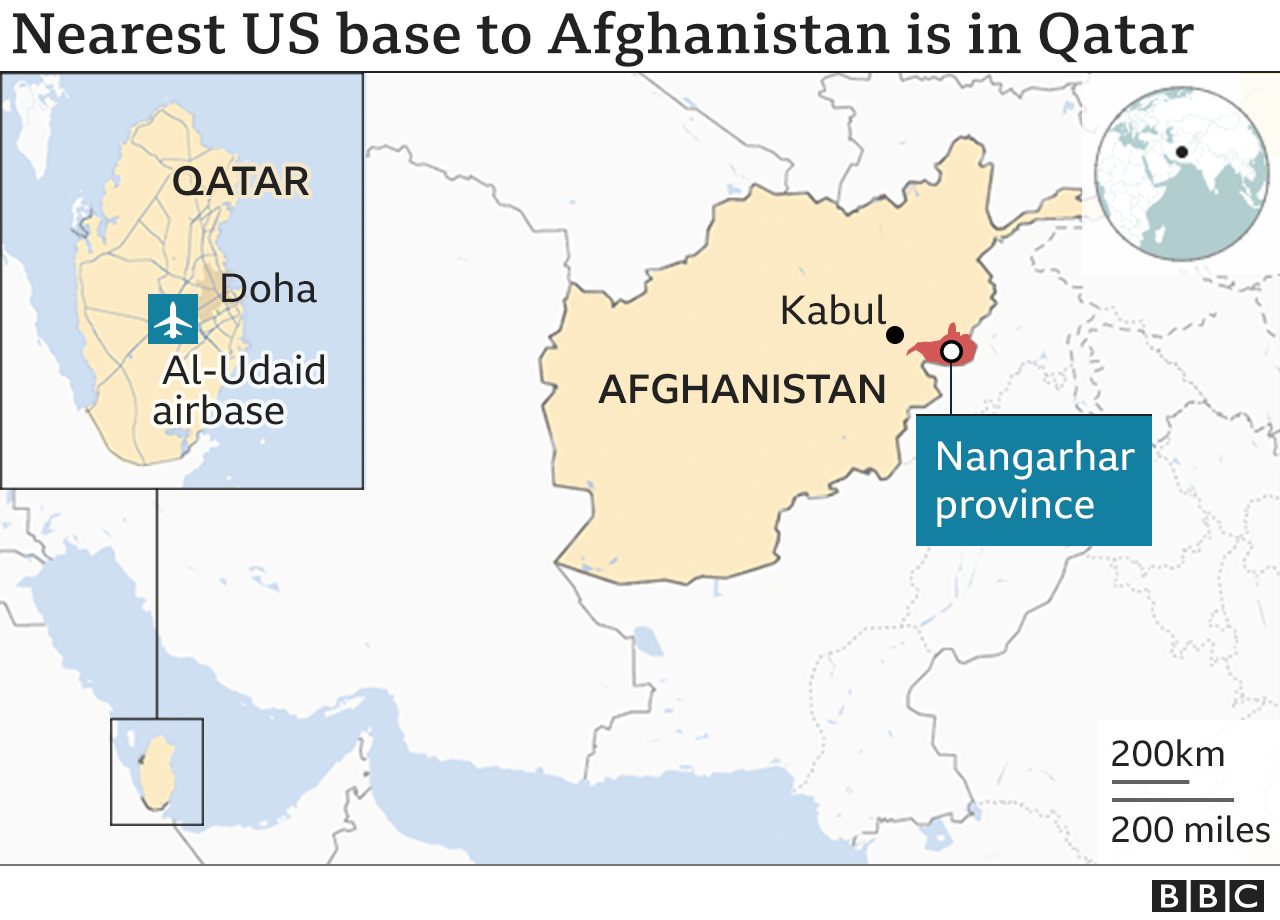

The fact that the US was able to locate and strike an ISIS-K target in Nangarhar province so soon after last Thursday's deadly bomb attack at Kabul airport shows that it still has some skin in the game - that it is not completely blind to what its adversaries are up to in the more remote corners of that country.

The US Central Command facility at Al Udeid airbase in Qatar maintains oversight of operations in Afghanistan, and when a target is identified it can call on a number of "assets" in the region to attack it, most notably missile-armed drones which are able to hover, unseen, over a location for hours on end.

But there is no getting around the fact that Afghanistan has now become a hard target for intelligence agencies. Most of those human informants who were supplying tip-offs on militant activities have either fled the country or gone into hiding.

Both MI6 and the UK government's listening station GCHQ ultimately report to the foreign secretary, so Dominic Raab will be well aware of the challenges ahead.

GCHQ, together with its US counterpart the National Security Agency, has been instrumental in locating ISIS terror cells in places like Syria and Iraq.

But for MI6 the reality is that it will need to rebuild an entire network of human informants if it is to successfully place agents "upstream" inside terrorist organisations in Afghanistan who can then give warning that an attack is being planned. And that could take years.

It is one of the bizarre oddities of the whole Afghan situation that the US and the Taliban, who have just spent the last 20 years fighting each other, now find themselves on the same page when trying to confront ISIS-K.

ISIS-K is a declared enemy of both the Taliban and al-Qaeda and is likely to become the new insurgent challenge to Afghanistan's new rulers.

But when it comes to al-Qaeda, the situation is a lot murkier.

According to a UN report published in June there remain strong ethnic and marital ties between the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

The purported return to Afghanistan this week of Osama Bin Laden's former security chief Amin ul-Haq is a worrying sign. That such a high-value individual, classified by the US as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist, should feel safe enough to return now the US has left will be deeply troubling for counter-terrorism officials in many countries.

They won't be taking their eyes off Afghanistan for many years to come.

Related topics

- Published11 October 2021

- Published31 August 2021