Covid debt: A baby, job loss - and now eviction

- Published

Tenants are being evicted due to rent arrears built up during the Covid pandemic, despite the government saying no-one should lose their home as a result of the crisis.

One-third of hearings monitored in England and Wales over the summer explicitly cited the pandemic as the reason for the arrears, an investigation has found. The average hearing lasted just 10 minutes.

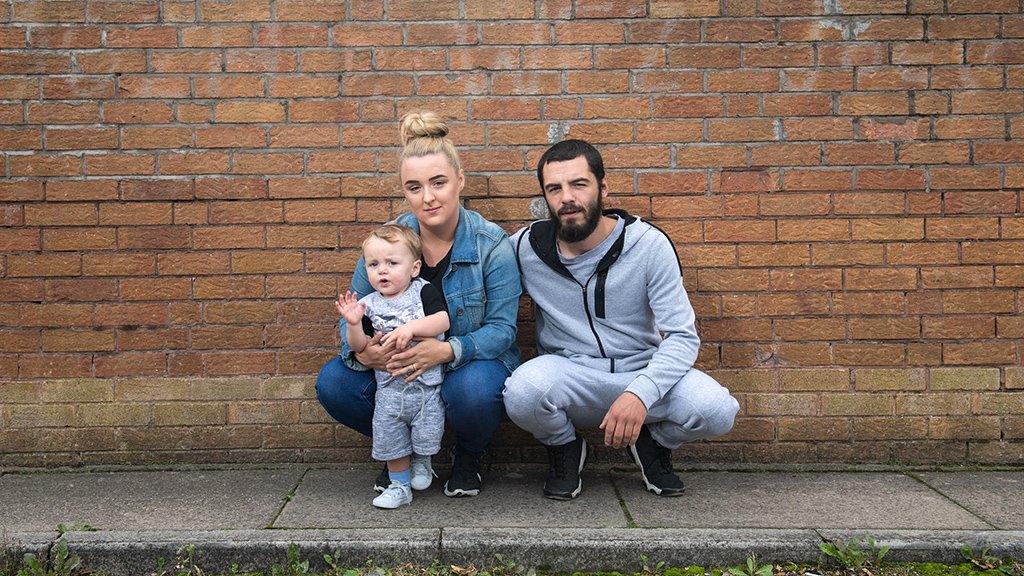

"We had a few safety nets, but they weren't enough for Covid," says Marshall Kinder-Maiss, 27.

Three weeks before the UK went into lockdown in March 2020, he and his partner Joanne thought their dreams had come true. After 18 months of trying to conceive a child, Joanne had just given birth to a baby boy, Roman. To support his growing family, Marshall, a chef, decided to leave his job at a Nando's restaurant in Liverpool to take a better-paid role with a city-centre cafe.

Marshall had a week off between his old job and his new one. And that was the week when Covid restrictions were introduced. Marshall's new job offer was withdrawn. And as he had left his former employer, he wasn't eligible for the government's furlough scheme.

The couple's income plummeted. Until their claim for Universal Credit was processed, their only money was Joanne's maternity pay of £150 a week. When the couple were both working full-time, they used to take home around £2,000 a month. Their £450-a-month rent quickly became unaffordable as overdrafts were maximised to pay for living expenses. They've struggled to pay rent ever since.

"It was not how it was supposed to be," says Joanne, 24. "It makes me feel a bit sick. We both grew up coming from poverty so we tried our best to get out of that. We've always been working people, and now I just feel like our son has been born into the exact same situation.

"All of our peers - they're not in this position. So it's a bit humiliating to be honest."

They are now £4,000 in rent arrears and have been served with an eviction notice. They must leave the house by 11 October.

In March 2020, former Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick tweeted that "no-one should lose their home as a result of the coronavirus epidemic". A ban on bailiff evictions was introduced in England and Wales. This ended in England in May this year, and in Wales the following month.

To investigate the impact of this, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) sent reporters to 30 county courts in England and Wales throughout July and August.

Of the 555 cases involving either private or social housing landlords, 270 ended in a possession order. A third of those, 88 cases, explicitly mentioned the impact that Covid had had on their finances.

Court bailiffs were "swamped" following the end of the eviction ban, lawyers told the BBC.

270ended in an outright possession order

88possession orders mentioned Covid

10minutes average case time

£6,500average (median) tenant arrears

Marshall and Joanne have decided not to go to Liverpool County Court to challenge their landlord's legal action. They have been advised by their legal representative that it would be "pointless".

They have been served with a Section Eight order, used when a tenant breaks the terms of the rental agreement. This acts as a mandatory ground for repossession if the landlord can prove that the tenant has arrears of at least two months.

Last year, MPs on the Housing, Communities and Local Government committee recommended changes in the law to give judges discretion in deciding each individual case. The government chose to ignore the recommendation.

On Monday, the BBC visited Wandsworth County Court - a crumbling three-storey building in south London - to witness possession orders being rapidly handed down, some within just five minutes.

The individuals or families in question will be forced out of their homes in just two weeks' time.

Only one tenant appeared in person during the session. She told the court she had been unable, during the pandemic, to find her usual agency work as an executive PA. This left her unable to afford the £1,600 a month rent on her one-bedroom flat in Hammersmith, west London.

She had racked up £24,000 in rent arrears. The court ordered her to leave her property by 4 October. In addition to her rent arrears, she must pay £604 in interest, and the landlord's £3,000 legal costs.

The woman, who did not want to be named, told the BBC she would stay with a friend for the first two weeks. She has no idea where she will live after that.

"I don't know what to do. I've found a job, but my credit history is so bad, I doubt I'll find a place," she said.

Marshall and Joanne say they have the same problem.

Marshall found a new job three months ago, working for a food delivery firm, and is now looking for a second job to supplement his wage. But they don't have any savings to pay a deposit, and their credit rating is now poor.

And they face fierce competition for a new home, says Joanne.

"They're really sought after because there are a lot of evictions, so people are desperate to get a house."

Marshall says he phones the council an average of once a week to enquire about social housing, but has been told there are others whose need is greater.

The couple say they definitely plan to pay back their arrears once they are able to.

The average tenant in the cases analysed by the TBIJ had £6,500 worth of rent arrears. But a judge at another London court told the BBC he had come across one set of tenants with arrears of £190,000 in recent weeks. Some tenants had "undoubtedly taken advantage" of the evictions ban, he said, in effect to live rent-free.

Landlady Michelle Dighton, 41, believes this is the case with a tenant in one of her rental properties.

She is owed more than £25,000 in rent arrears as she says her tenant - in Croydon, south London - hasn't paid rent since October 2019. She says that she delayed serving an eviction notice, hoping to resolve the situation amicably.

But when the government introduced the eviction ban, Michelle found herself stuck. Legal delays have further prevented the mother-of-two from sending round the bailiffs.

"I have to pay a mortgage and service fee for the flat, but I'm not getting any income from it."

Advice for tenants from the Citizen's Advice Bureau:

You can only be evicted if your landlord has followed the proper steps, external

Talk to an adviser as soon as possible, external if you are served papers or visited by bailiffs

You may be eligible for emergency housing or a hostel if you need immediate help, external

Michelle says, as a tenant herself, she understands why the government introduced the eviction ban, "but the courts can't distinguish between those who can't pay and those who won't pay".

"My tenant's arrears have nothing to do with Covid," she thinks.

Although the majority of tenants whose cases were monitored by TBIJ were served a Section Eight eviction notice, a fifth were served a Section 21 notice. Section 21 is a controversial part of the 1988 Housing Act which allows landlords to evict people without giving a specific reason. Often called "no fault" or "revenge" evictions, the Conservatives promised to scrap them in their 2019 manifesto.

Ministers said they will outline their proposals "in due course".

In a statement, the new Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities said: "Our £352bn support package has helped renters throughout the pandemic, and prevented a build-up of rent arrears. We also took unprecedented action to help keep people in their homes by extending notice periods and pausing evictions at the height of the pandemic.

"As the economy re-opens, it is right that these measures are now being lifted and we are delivering a fairer and more effective private rental sector that works for both landlords and tenants."

A Welsh government spokesperson said: "Here in Wales, we have made significant additional help available for tenants, including additional funding for Discretionary Housing Payments and grants to clear Covid-related rent arrears. This support goes far beyond any support UK government have provided."