How millions don't know they're related to royalty

- Published

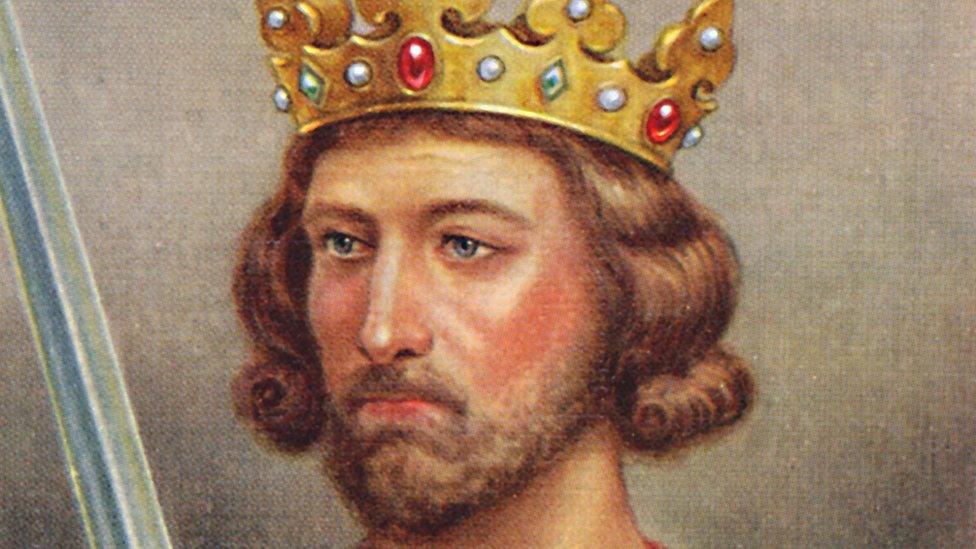

Josh Widdicombe found he was related to Edward I. But genealogists say it's much more likely than people expect

It might seem like an unlikely and rare connection. How could a modern-day comedian turn out to be related to a medieval monarch?

On a recent episode of the TV genealogy show Who Do You Think You Are? Josh Widdicombe discovered he was a descendant of Edward I, who died more than 700 years ago.

But he hasn't been the only example. Soap star Danny Dyer found on the BBC family history show he was related to Edward III, Alexander Armstrong was descended from William the Conqueror and the rower Sir Matthew Pinsent was another relative of Edward I.

So what's going on? Are the genes that put kings on thrones now producing a celebrity aristocracy? Or are these just remarkable and unusual, needle-in-a-haystack, coincidences?

What this really shows, according to genealogy experts, is that if you look back far enough a surprisingly high number of people will find a royal ancestor.

Can you prove it?

"It's not that uncommon," says Graham Holton, a tutor on a postgraduate course on genealogy at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow. And to illustrate the point, he's also another descendant of Edward I.

"Whether you can actually prove it is one of the issues. Probably lots of people who are would not be able to prove it with documentary evidence," says Mr Holton.

Using previous models of the numbers of descendants over the generations, he says as a broad estimate there could be two million people alive now related to Edward I. Because the records of most ordinary families would not stretch back that far, most people would not know about their link.

But it means that on any street or crowded bus there could be an unwitting relation of this medieval monarch.

Mr Holton wasn't necessarily delighted about his royal connection. "It was very interesting. But being a Scot and Edward I being known as the Hammer of the Scots, I wasn't absolutely over the moon."

Millions related to Richard III

Turi King, professor of genetics at the University of Leicester, has researched Richard III and says there are "literally millions" of people alive now who are related to the immediate family of this 15th-Century sovereign.

It was living descendants of one of his sisters that enabled researchers to use DNA to help identify the bones of Richard III found in Leicester.

Prof King, a presenter on BBC Two's DNA Family Secrets, says that it's often not understood how much family trees are likely to overlap when you go back so many generations.

"I always say to people we are all related to each other. It's just a question of degree."

Genetics professor Turi King says we are all much more interrelated than might be recognised

It's partly the sheer numbers. By the time you go back more than 20 generations or so, based on the average reproduction rate, everyone will have millions of ancestors. Rather than separate trees, she says family links become like interwoven thickets.

The idea of royalty is wrapped in ideas of being special and apart - but Prof King says the genetic reality is that we're all the product of centuries of mixing and merging, migration, social rises and falls, interrelated in many ways.

Many of us will have shared ancestors. And if someone has ancestry in Britain going back to the Middle Ages, Prof King says it's actually more likely than not they will be related to a branch of one of the royals.

But when a TV show focuses on such a link to a monarch, she has to "try not to shout at the telly" about the huge number of other less glamorous ancestors who are being ignored on the way.

Once you go even further back, a few thousand years or so, the genetics professor says there are even bigger patterns of common ancestry, not just within Britain, but shared between people living in different countries and continents.

"We're all part of a giant family," says Prof King.

Being able to navigate a path back to an identifiable medieval relative often depends on finding a "gateway ancestor", says Else Churchill, a genealogist at the Society of Genealogists in London.

Edward I could have a descendant in any street, with millions of his family alive now

This would be someone rich, famous or perhaps infamous enough to be well documented and provide a trail for a family historian. And if someone has such a pathway, she says it's "fairly likely" they will bump into a royal relative.

She says a genealogy study suggested that a child born in England in the middle of the 20th Century, who could trace their ancestry back to England in the early 13th Century, would have 80% of the population of the time in their family tree.

"We're reliant on the survival of records," she says. "We've all got the same number of ancestors, we just don't always know their names," she says. And many of us will have "lineage going straight back to a bunch of peasants".

Unexpected DNA result

Else Churchill found a surprise in her own DNA results

People are increasingly turning to DNA for family links. And Ms Churchill found her own unexpected history. But it wasn't about being related to a medieval king.

"I've discovered through DNA that my father is not my father.

"So I've been researching the Churchills for 40 years, so that came as a bit of a shock. I had no inkling," she says.

"I do know people who have been rocked by finding something like that. Personally I wasn't, but it did make me start thinking about identity."

Ms Churchill, whose parents are no longer alive, says it made her realise that she hadn't lost any sense of identity by finding out this lack of a genetic connection to her father or the ancestors she had researched for so long.

It didn't change her sense of family relationships, and it also didn't dampen her enthusiasm for the detective work of genealogy.

"I don't get my identity by thinking that back in 1630 there was a guy called Thomas Churchill who's my ancestor. He's interesting historically, but he's not really me.

"Family is not necessarily genes, and family isn't necessarily ancestry," she says.