Councils to be forced to take child asylum seekers

- Published

Councils across the UK are to be forced to care for some of the unaccompanied asylum seeker children who have arrived via the English Channel in small boats.

Immigration minister Kevin Foster said the decision was not taken lightly but was in the children's best interests.

Authorities will take children now being looked after by Kent and other councils on England's south coast.

More than 100 children are living in hotels because of a shortage of places in children's homes.

The change will see all 217 UK authorities with social services departments obliged to accept an allocation of the children.

The Home Office said it was taking "urgent steps" to allocate places in care for asylum-seeking children.

It has sent councils across the UK a letter giving them two weeks to present reasons why they should not accept them.

The letter says they will not need to accept more asylum-seeking children if they are already caring for a number that makes up 0.07% of their general child population.

The government will pay councils £143 per child per night under the scheme.

Speaking in the Commons on Monday, Home Secretary Priti Patel said councils around the UK needed to "play their part" in offering accommodation to asylum seekers.

The vast majority of councils have already offered places to unaccompanied children, according to Nick Forbes, chairman of the Local Government Association's asylum, refugee and migration taskforce.

But the Labour politician told the BBC he was "very disappointed" that about 15 to 30 councils - out of 217 - were yet to take any children.

Mr Forbes, who is also the leader of Newcastle City Council, said some local authorities were reluctant to volunteer due to the "chaotic asylum system" and national shortage of social workers and foster care placements.

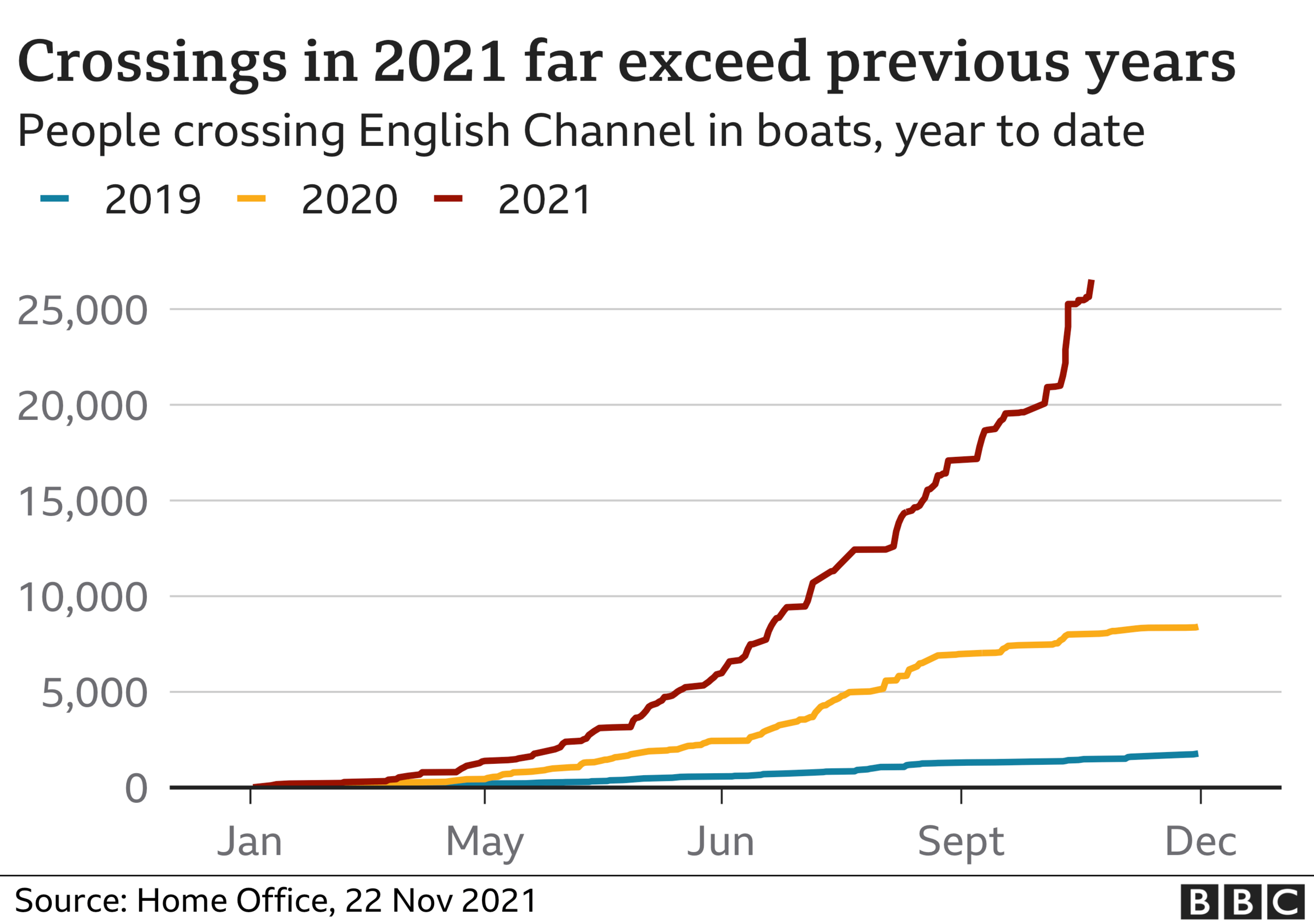

It comes as the number of migrants to have reached the UK by boat this year has risen to more than three times the 2020 total. The Home Office said 886 people arrived on Saturday, bringing the 2021 total to more than 25,700. The figure for last year was 8,469.

However, increased security and Covid restrictions have made traditional routes less viable for migrants and the overall number of people to have claimed asylum in the UK in the 12 months ending June 2021 was 31,115, a 4% year-on-year fall.

The people who cross the Channel come to the UK from the poorest and most vulnerable parts of the world - including Yemen, Eritrea, Chad, Egypt, Sudan and Iraq.

Under international law, people have the right to seek asylum in whichever country they arrive, and there is nothing to say they must seek asylum in the first safe country. It is very hard to apply to the UK for asylum unless you are already in the country.

Enver Solomon, chief executive of the Refugee Council, said the government decision to compel councils to take unaccompanied children was "important". He said it "should reduce the unacceptable delays in vulnerable children, who have often experienced great trauma, getting the vital care they need".

However, local government sources say there are concerns about the funding councils - which are already under financial pressure - will receive.

The Conservative leader of the Local Government Association, which represents councils in England, Councillor James Jamieson, said: "These new arrangements must continue to swiftly take into account existing pressures in local areas."

The home secretary criticised Scottish councils in the Commons on Monday for the numbers of children they had taken.

Kelly Parry, an SNP councillor who speaks for the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities, said they were committed to participating on a voluntary basis and were already providing a "proportionate share" of placements.

What happens to migrants in the English Channel?

If migrants are found in UK national waters, it is likely they will be brought to a British port

If they are in international waters, the UK will work with French authorities to decide where to take them

Each country has search-and-rescue zones

An EU law called Dublin III allows asylum seekers to be transferred back to the first member state they were proven to have entered but the UK is no longer part of this arrangement and has not agreed a new scheme to replace it.

Additional reporting by Alex Kleiderman and Dulcie Lee

STING - 'IS THAT MY DESTINY?': The 100 million selling artist on family and fame

IN PRISON WITH NELSON MANDELA: Fellow inmate Ahmed Kathrada speaks about being imprisoned under the Apartheid regime

- Published13 December 2023

- Published20 November 2021

- Published22 November 2021

- Published22 November 2021

- Published9 September 2021