Magistrates to get power to jail offenders for a year

- Published

Magistrates in England and Wales will have greater sentencing powers to enable them to take on more cases, under plans to clear court backlogs.

The government plans to let magistrates sentence cases where the maximum sentence is a year, rather than the current maximum of six months.

It would allow magistrates to hear cases often held in Crown Court.

But criminal lawyers warn the plan may backfire, and defendants would still have the right to go before a jury.

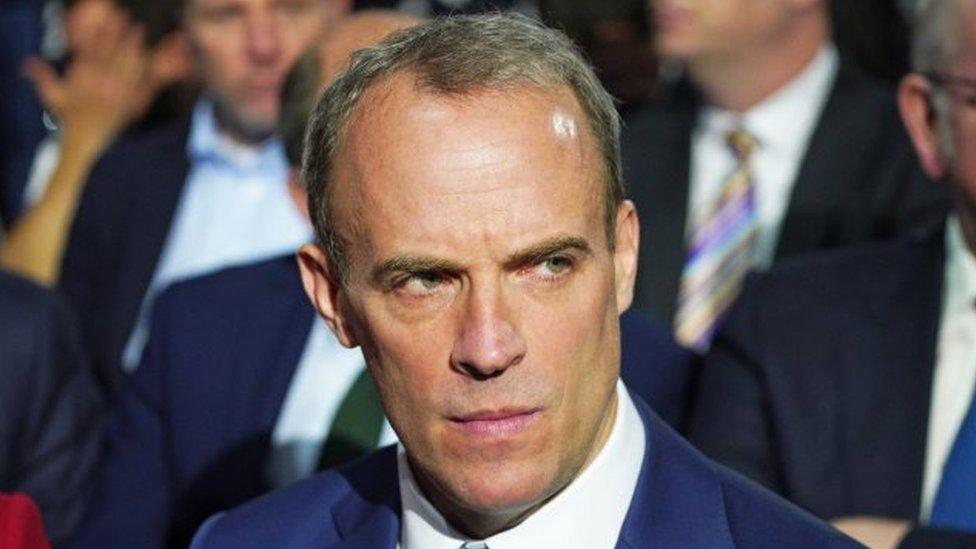

Justice Secretary Dominic Raab said he hoped the move would reduce the pressure on Crown Courts and lead to quicker justice for victims.

The move would allow magistrates - who are volunteers with no legal experience necessary - to sentence more serious cases, such as for fraud, theft and assault.

At present, crimes eligible for a jail term of more than six months have to be sent to a Crown Court for sentencing.

The Ministry of Justice thinks that by doubling magistrates' sentencing powers to a year, it could stop about 500 cases going to Crown Court - giving judges around 2,000 extra days to handle more serious crimes.

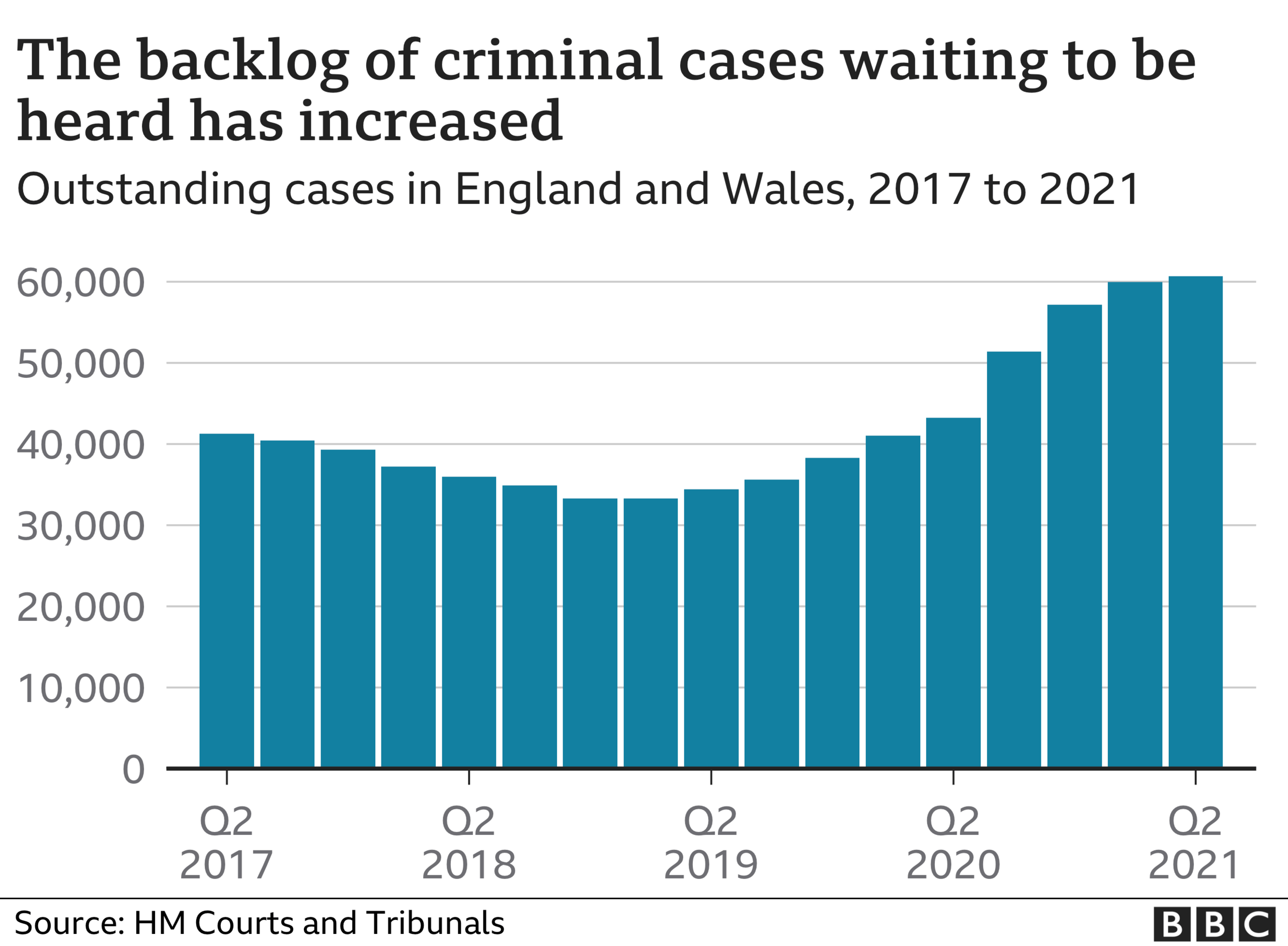

The courts system is facing unprecedented delays - and as of June last year there was a record high of more than 60,000 Crown Court trials waiting to be heard.

Many serious cases are being pushed back until late 2023 - with alleged victims saying they are struggling to cope as they wait for their cases to be heard.

The changes will only apply to so-called either-way offences - cases that can be dealt with either by magistrates or by judges at a Crown Court. A defendant charged with an either-way offence can insist on the case being heard by a jury in a Crown Court if they wish.

The prime minister said it would "help tackle the backlog of cases in the Crown Courts - speeding up justice for victims, punishing those guilty of serious crimes and building back stronger and safer from the pandemic".

He said increasing magistrates' sentencing powers would mean that cases came to court quicker meaning "greater justice for victims" and "more criminals seeing justice quicker".

Mr Raab said the move would help provide additional capacity to drive down the backlog of cases, alongside measures such as the temporary Nightingale courts.

Like Nightingale hospitals, these courts are temporary courtrooms - such as in hotels - that have been set up across England and Wales to try to deal with more cases.

The announcement comes as the trial of Wales manager Ryan Giggs was delayed until August due to a lack of court space. The former Manchester United player, 48, was due to go on trial at Manchester Crown Court on Monday accused of coercive behaviour and assault against his ex-girlfriend and her sister.

However, a hearing was told there was nowhere available in the building.

Judge Hilary Manley said: "Due to the large backlog of court cases, which has been exacerbated by the pandemic and the need for social distancing, this is a situation which is a daily reality for the criminal courts."

Mr Giggs has pleaded not guilty to the charges.

What do barristers think of the change?

This change in sentencing powers for the lowest criminal courts was put into law almost 20 years ago but never used at the time.

The government is clear it's pulling the lever now because it reckons it will create some breathing space for the Crown Courts.

Barristers say it will make little difference and the real solution can only be found in urgently needed cash to reverse years of cuts.

They say that while the Crown Court backlogs are at record levels, that's not because there's more crime, but a lack of resources in the system to deliver justice efficiently.

Criminal barristers are actively talking about staging some form of strike or work-to-rule if the government does not act swiftly on recommendations last year for a significant increase in legal aid funding.

If that materialises in the coming months the Crown Courts could grind to a halt.

Ministers plan to monitor how the extra powers for magistrates are used - but many lawyers predict it will backfire.

They say more defendants may appeal against sentences given by magistrates, many of whom have no legal qualifications - or there could be a spike in the prison population, further stretching the government's budget.

The Bar Council, representing all barristers in England and Wales, also warned that more defendants may exercise their right to go before a jury - adding to the already enormous pressures in the system.

And the chairman of the Criminal Bar Association (CBA), Jo Sidhu, said "fiddling with magistrates' sentencing powers is a betrayal of victims of crime".

Kirsty Brimelow, vice-chair of the CBA, told Radio 4's Today that the increase of sentencing powers for magistrates would cause more defendants to choose to go to the Crown Court as the lower sentence was one of the attractions of staying in the lower court.

"Sadly the stats do show that you are more likely to get imprisonment within the magistrates' court than you are in the Crown Court," she said.

Ms Brimelow said increasing magistrates' powers could lead to more appeals which would take up magistrates' time.

"The issue of the backlog, which was there before the pandemic, is not really about sentencing powers, that is just rearranging the deck chairs, it is about lack of investment," she said.

She said there was a "huge attrition" of barristers leaving the profession and warned that 96.5% of the CBA's members were willing to take action if there was not a substantial increase in fees into legal aid.

Mr Raab said that the one thing that would hold back the court system's recovery from the pandemic would be if the CBA went on strike, which he said he did not think other parts of the justice system or the public would support.

Stuart Matthews, partner at criminal defence firm Reeds Solicitors, also warned people to "be afraid" - describing magistrates as largely "untrained volunteers, many of whom do not understand even the most basic of legal principles".

WATCH: Two young lawyers share their concerns about the profession

Labour's shadow courts and sentencing minister Alex Cunningham also criticised the move, calling it "another sticking plaster" solution.

"Ministers must give assurances that greater powers for magistrates won't inflict even more burden on Crown Courts - with increased numbers of appeals overloading a diminishing number of criminal advocates left in the system."

How do you become a magistrate?

Magistrates are volunteers who hear cases in criminal and family courts, aided by a legal adviser

To become a magistrate you do not need qualifications but must be aged between 18 and 65 and of good character - among other qualities

Around 21 hours of training is required to become a magistrate and you must be able to sit in court for at least 13 days a year

They are unpaid but some employers allow their employees time off paid and you can claim an allowance if you miss out on pay

Source: UK Government, external

But magistrates say they are delighted.

The Magistrates' Association - which had campaigned for sentencing powers to be extended - said magistrates would take up the new responsibility with pride and professionalism, and would "strive to deliver the highest quality of justice".

The changes are expected to be brought in in the coming months.

The government said training would be provided by the Judicial College to make sure the powers are used "consistently and appropriately" - and the government will have powers to reverse the change if needed.

Last year, the spending watchdog the National Audit Office said the Crown Court backlog could remain a problem for years - and there could still be significant delays in 2024.

And in October, Mr Raab told the BBC he did not know when the backlog would drop below pre-pandemic levels.

WHAT IS AN 'ANTI-DIET'? The food movement that could change your attitude towards exercising

FOR THE NHS, THE FIGHT GOES ON: How is the health service coping two years into the pandemic?

Related topics

- Published16 December 2021

- Published22 October 2021

- Published14 October 2021

- Published16 December 2021