P&O Ferries: 'We've been abandoned by the company', say sacked staff

- Published

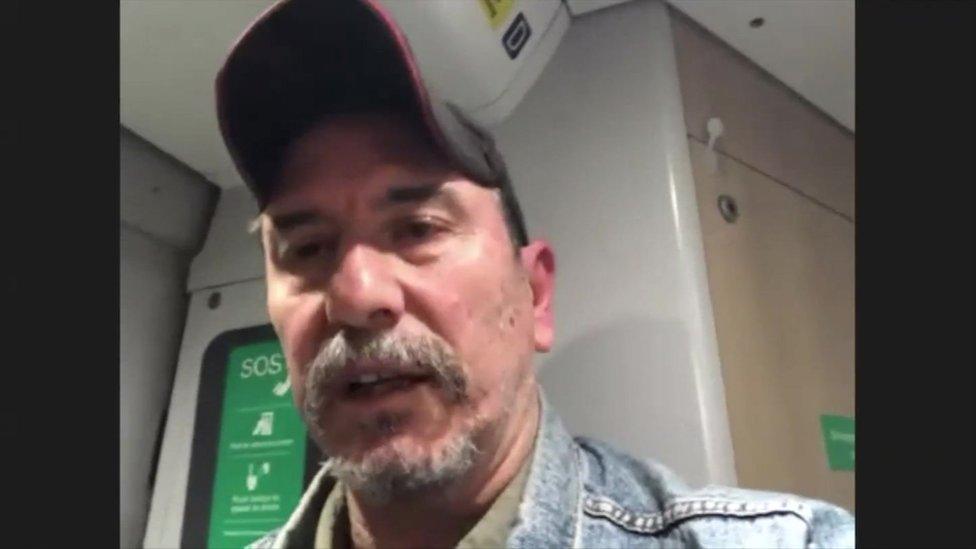

Sacked P&O employee Andrew Smith said he felt "utter dismay" at losing his job after 22 years' service

Seafaring staff at P&O Ferries were told by video message that 800 of them were being sacked immediately as their ships returned to port. The decision has sparked angry protests from staff on ship and shore.

Darren Proctor, national secretary for the RMT union, says he woke up to a flurry of messages from people worried about what the company was about to announce.

Heading down to Dover, he was told that coaches with private security guards were travelling to the P&O port on the south coast of England, as well as Hull, Larne and Cairnryan. "They had to be handcuff-trained," he says.

Then at 11:10 GMT, their worst fears were confirmed: 800 staff were told they were immediately redundant.

Mr Proctor says some staff remain on the three ships at Dover, but some have left and security staff have boarded to try and put their replacements in post.

James, a steward on board the Spirit of France ferry at Dover, was on a day off when he heard the redundancy announcement.

He was texted half an hour before the three-minute video from P&O management.

"It feels like we have been abandoned by the company, only a few days ago they were ordering new uniforms and giving us all a pay rise and now, completely out the blue, they have sacked us," he said.

James, who did not want to give his surname, said staff were told that they would be given a "generous severance package" in the video message but staff were not able to ask questions after the call and no details about redundancy pay were given.

"How they expect to run an entire fleet of ships with fresh, inexperienced crew I will never know - it won't be smooth sailing," he says.

'We felt we were traitors'

Speaking to the BBC as he took the train home, Mark Canet-Baldwin says workers hired to replace P&O staff were "appalled" by the company's plans

Mark Canet-Baldwin from Hull says he was hired a week ago to work as onboard services manager on a new ship sailing in British waters, but the agency couldn't tell him anything about the ship.

He was put up in a hotel in Glasgow and then driven at 05:30 GMT to an undisclosed location, which turned out to be the P&O dock at Cairnryan.

Their bus stopped to pick up a security detail of a dozen guards, "all in black, big handcuffs on the back of them", Mark says.

When they arrived, some agency staff knew the P&O workers as former colleagues and got in touch.

"People on board were just devastated," Mark says. "It was just horrible, we were appalled, there was just a general feeling of uneasiness on the bus and we felt we were like traitors to the cause or something."

One sacked P&O staff member had just taken out a mortgage, he says, and they had all been expecting to arrive home for two weeks of leave, not redundancy.

"I've got kids and I started thinking about them. In this day and age you've got to have morals, you've got to have ethics," Mark says.

He says he took off his hard hat and overalls and, along with three others, got off the bus and went home.

On board the Pride of Hull, staff stayed put after the shock announcement.

Gaz Jackson, an RMT officer who boarded the ship in Hull's King George Dock early on Thursday, said cheaper replacement staff were parked outside the port waiting to get on board, while another van held what he believed were security staff.

He said the captain made a "brave decision" to lift the gangway for the crew's safety, saying security guards were going to "pull us off if we weren't going to get off".

The RMT union held a protest at Dover following the mass sacking of 800 P&O staff

The protest meant other workers with no connection to the P&O dispute had also been trapped on the ship.

Keith Davis had been repairing some kitchen equipment with eight other contractors when the captain lifted the gangway. "We're being held against our will," he said.

Later on Thursday afternoon, the stern doors of the Pride of Hull were seen to open and a few vehicles came off, however.

The P&O Ferries crew told the BBC they intended to stay on board for "as long as it takes".

But after a stand-off lasting for several hours, the crew eventually disembarked at around 16:30 GMT.

Mr Jackson said they ended their protest after the company agreed to provide paperwork requested by the union.

"The crew are absolutely devastated. I've seen grown men crying on there because they don't know where they're going to go from today," he said.

'I'm fuming'

In Larne, one man who had worked for P&O Ferries for nine years said security staff came on board their ship to make sure everyone left.

He said: "We went through a lot over the last two years with the pandemic and all that kind of stuff, but didn't think it would end like this."

Dozens of workers also blocked roads at Dover in protest, with some clashing with motorists as they stood in the road with banners and flags saying: "Stop the P&O Jobs carve-up".

Some insisted they would not move until the police came to take them away.

One 54-year-old man, who has worked in ferry engine rooms since the 1980s, told the PA news agency: "I'm fuming, to be honest with you. I've known people who've been with the firm for years - this is no way to treat people.

"It was just a short message this morning saying you've all lost a job, basically - all this service for nothing."

Some staff are refusing to leave the three ships at Dover - and others at three more UK ports

The protesting members of staff want P&O Ferries to begin talks with them over their jobs, but the RMT national secretary Mr Proctor says: "This is a company that doesn't want to negotiate at all, there's been no dialogue with them whatsoever and they've obviously been organising this for a long time."

Asked if it was true, as the company suggested, that P&O management had no choice, he said it had been financially mismanaged for years.

"They've chosen to go for the jugular of UK seafaring," he says.

Now staff want support from MPs and government and they are trying to drum up international backing from workers in foreign ports.

"If they can do it here, they can do it at another site and that can't be allowed to happen," says Mr Proctor.

NORWAY'S SEED VAULT: These mysterious places are out of bounds for the general public

ENHANCE YOUR CRITICAL THINKING: Why getting it right might mean admitting you're wrong

Related topics

- Published18 March 2022

- Published17 March 2022

- Published17 March 2022