Grenfell Tower: Official admits he could have prevented fire

- Published

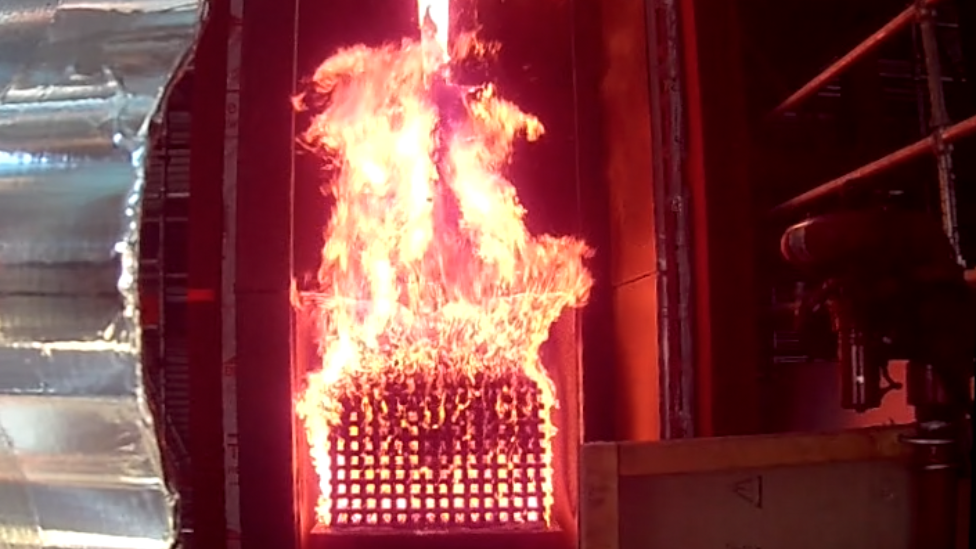

Flammable cladding panels have been blamed for the rapid spread of the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire, which led to 72 deaths

A civil servant has admitted he could have potentially prevented the Grenfell Tower fire on a number of occasions.

Brian Martin, the head of technical policy for building regulation, told the public inquiry that he found it hard to express how sorry he was.

Mr Martin was questioned about warnings he was given that the building industry, confused by government guidance, was using dangerous cladding.

He admitted not realising the severity of the risk at the time.

Mr Martin, said "over the last few months I've been looking through evidence and documents and when you line them in the way we've done in the last seven days [at the inquiry] it became clear to me that there were a number of occasions where I could have potentially prevented this happening".

But Mr Martin also pointed to government policies deregulating the industry that left him as "a single point of failure" in an under-resourced department.

Brian Martin was told about fire tests on cladding panels which caused a "raging inferno" in 2001

In 2001, he was told about fire tests on cladding panels which caused a "raging inferno" but he failed to realise the significance of the results. He told the inquiry "it just got missed".

The test results were kept largely confidential.

He was also warned about a number of fires involving cladding on tall buildings abroad, but reassured other government officials that it should not happen in Britain because of building regulations here that banned the use of combustible insulation.

But they did not specifically ban combustible cladding.

Mr Martin admitted becoming "entrenched in a position" where he focused on his role of improving the government guidance for which he was responsible but "didn't realise just how big the problem was".

'Under the radar'

It was only in 2006 that a section was added to government guidance, by Mr Martin, which prevented the use of flammable "filler" materials being used on tall buildings.

The inquiry heard this was done without consultation, and at the last minute, "under the radar".

Mr Martin gave evidence that he intended this to cover cladding, but had not been specific. The government did not want to stifle the building industry's ability to be innovative.

He faced repeated questions about the use of the word "filler" rather than more specific language, because it led to widespread misinterpretation of the guidance within the cladding industry.

The government responded to Grenfell by banning combustible cladding a year after the disaster, on the strength of new tests carried out after the fire

Another section of the same government guidance appeared to allow the use of the most common form of aluminium and plastic cladding.

A series of industry bodies told him the guidance was not clear but he didn't change it, despite being in charge of the building regulations.

Mr Martin insists that an advice note put out by one industry association was enough to inform architects and builders what the true meaning of the guidance was.

But in 2014 he left early from a meeting with industry figures to discuss the "numerous inquiries" there had been from cladding firms about the issue.

In 2016 combustible cladding was chosen by the Grenfell Tower refurbishment project, added to the sides of the building by an installation firm, and signed off by building control inspectors.

At no point was it suggested the combustible panels might not comply with the building regulations.

Mr Martin told the inquiry in his closing statement that if he'd realised the scale of the problem: "I would have escalated the issue and perhaps we'd have done something to prevent what happened to the people of Grenfell Tower."

However he also attacked the policy of several governments which pushed for the deregulation of safety in the building industry.

From 2010 onwards the Coalition government had a policy of cutting red tape to allow more freedom for construction firms.

This meant that instead of fire brigades or a building regulator having control over safety, companies and building owners were left to regulate themselves, with the main requirement being to ensure that building design and materials could not spread flames.

'Professionally reckless'

Ministers will face tough questions in the next few weeks about the policy of deregulation.

On Wednesday, the first government minister to give evidence at the public inquiry defended his decision not to increase the regulation of fire safety despite warnings.

Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis MP was responsible for fire safety in the years before Grenfell.

Mr Lewis decided the fire safety industry should regulate itself and told the inquiry he had ideological and practical concerns about increasing the role of government.

"Our entire ethos was about devolving power from central government rather than bringing it in," he said.

The government at the time had an explicit policy of getting rid of 'red tape', including health and safety requirements.

The inquiry has heard that from 2005 there were growing signs that the housing industry was using "cowboys" without formal qualifications to assess buildings.

The assessor who inspected Grenfell Tower was described as "professionally reckless" by an expert witness because he signed off the building's cladding as safe, without evidence.

The role of the government in the Grenfell fire is now the prime focus of the long-running public inquiry, which is in its final stages.

Government lawyers have already apologised for "past failures in relation to the oversight of the system that regulated safety in the construction and refurbishment of high rise buildings."

A series of ministers will give evidence in the next few weeks.

You can follow the latest developments from the public inquiry on The Grenfell Tower Inquiry Podcast.

Related topics

- Published15 February 2022

- Published7 February 2022

- Published14 June 2020

- Published30 March 2020