Ukrainian refugees are now living in the UK - so how is it going?

- Published

Tanya Sazanova and her daughter's hosts met them at the airport with a Ukrainian flag

Tens of thousands of Ukrainian refugees have fled the Russian invasion and are now living in the UK. But two months on, how has it been working out and are there areas of concern?

More than 60,000 people fleeing Ukraine have arrived in the UK - some with family visas and others under the Homes for Ukraine sponsorship scheme, which enables members of the public to host an individual or group. Latest figures show 115,000 visas have been issued.

But the experience of settling into life in the UK has differed wildly for many Ukrainians.

While there are many positive stories, charities have also warned of overcrowding, a lack of financial support and the risk of homelessness - particularly for people arriving on the family visa scheme that enables Ukrainians to join relatives who were already in the UK.

Family hosts are struggling

There is a "lot of pressure" among Ukrainians living in the UK to bring as many relatives over as possible, according to Kate Smart, CEO of the advice charity Settled.

She says this can lead to people saying yes to "more than they can cope with", and is something we are "most concerned" about.

"So people are ending up at the doors of local authorities needing homeless accommodation," Kate adds.

She says part of the problem is that those hosting their own relatives need more financial support.

Under the sponsorship scheme, hosts are entitled to a monthly £350 tax free payment - but people hosting family members are not.

Lack of support for some

"It's been the hardest time of our lives," says Natalia Korchevska, a Ukrainian woman in the UK who has opened her home to relatives fleeing the war.

For the past two months she has been living in a house of nine people.

Natalia and her husband welcomed her sister and family, as well as her husband's sister, to their five-bedroom house in Staffordshire.

"I know it's my family and I want to help," she says. "But I want the government to help a bit more."

"We've had no support at all," she says, from financial support to government guidance, since her relatives arrived on family visas.

A bunkbed was donated by a local group after Natalia Korchevska's family came to the UK

The communities department says people on both family and sponsorship visas have access to the same services as UK nationals, and councils are receiving £10,500 in funding for each arrival under the sponsorship scheme.

Natalia, who works for the NHS, explains that a change allowing people who have travelled on a family visa to switch to the sponsorship scheme would really help. "I'm frustrated and not happy, but it's my family so I will support them."

Rising risk of homelessness

While many relationships between hosts and refugees are positive, some Ukrainians have ended up needing homeless accommodation as a result of relationships breaking down.

Kate Smart from the Settled charity says she is "getting quite a few calls about it".

And councils are "already seeing a concerning increase in homelessness" among those who have arrived from Ukraine, says Cllr James Jamieson, chair of the Local Government Association.

In those cases, it would be best if families were "re-matched" with a new sponsor so they "can rebuild their lives in their new communities," he says.

One Ukrainian refugee who recently arrived in north-east England says she and her teenage son were left homeless after being manipulated by their hosts.

"I am fleeing the war and all of a sudden I am on the street," says the woman, 45 who fled Bucha, north of Kyiv.

The mother and her 13-year-old son - whose identities are being protected - told the BBC she thought her hosts would be kind and caring, but within weeks she "did not feel safe or secure".

More than 60,000 people have arrived in the UK from Ukraine

If there is a breakdown in relationships, re-matching should be the priority, rather than temporary homeless accommodation, agrees Sara Nathan from Refugees at Home.

More briefing before arrival, financial support to relatives hosting family members, and an awareness that hosts are not wholly responsible for their guests' wellbeing, are also among Sara's proposals.

"The hosts are doing a great thing by providing shelter, warmth, food and a listening ear, but they can't be 100% responsible."

The government says "very few" of these sponsorships are breaking down, and when they do local authorities have provided support or found a more suitable sponsor.

Difficulty choosing where to settle

Choosing a location in the UK can be "tricky" for Ukrainian refugees, according to Sara Nathan, who has hosted refugees in the past.

People coming often want to live in cities or towns to avoid feeling "isolated and lonely," she says.

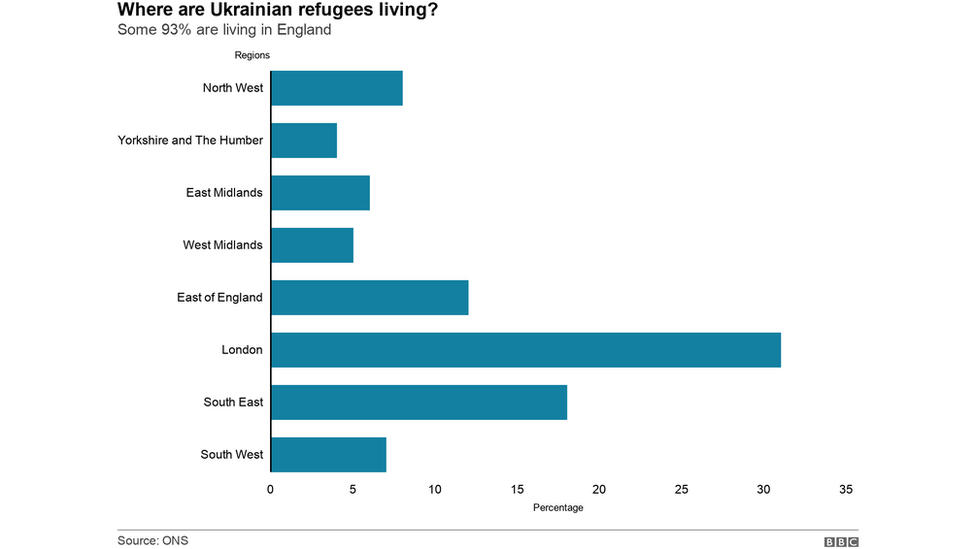

Some 93% of Ukrainian refugees are living in England and more than a third live in London, research from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows., external.

The figures, collected in April, also show that 69% would prefer to live in an urban area and 36% said London was the place in the UK they most wanted to live.

Anastasia Salnikova, who is from Ukraine and volunteers helping refugees in the UK, says she would encourage people not to go to London because it can be "a hectic and busy place" and difficult without language skills.

But people feel frightened and want a community so they "gravitate to London" she says.

A new country is scary - but you can find a warm welcome

Tanya Sazanova and her daughter Sonya visited Henley with their hosts

Tanya, a translator from Sumy in Ukraine - one of the first places targeted by the Russians, was in Kyiv for work on the day that war broke out, and ended up trapped there for a month.

She reconnected with her daughter Sonya and they travelled to Poland where she volunteered to help refugees - before applying to come to the UK through the sponsorship scheme.

Upon arrival they received lots of donations from the local community, including clothes, food parcels and a bike - and their hosts used flags to decorate their room.

"People are really lovely and kind here," says Tanya, adding they have received lots of welcoming messages from people on Facebook.

Tanya urged people coming from eastern Ukraine, "don't be afraid". "It was really scary in the first few days, but nothing like the first few days when the war started.

"I would say thank you to all the British people - from human to human, thank you."

Willing sponsors still needed

Anastasia Salnikova says it is getting more "difficult" for those wanting to come to the UK to find sponsors.

"The good thing is a lot of people… are very willing," she says, adding that Facebook posts get "lots of responses".

The first wave of people who came to the UK were generally those who escaped early and had a bit of money, but those who are only recently free from places like Bucha and Mariupol are "in a disadvantaged situation".

More than 100,000 Britons signed up as potential hosts under the Homes for Ukraine scheme on its first day, but since then the momentum has slowed down, Anastasia says.

People are planning holidays so are less available, and others have been deterred by recent "negative publicity" about relationship breakdowns with hosts, she adds.

More support networks would help

Oleg Nedava and his wife were visiting their children in the UK when the war broke out

Oleg Nedava, who fled from Donetsk to Kyiv in 2014 and is now a refugee in the UK, has called for more support to create hubs "where we can all gather together to talk".

Oleg, a former Ukrainian MP, and his wife Irina were visiting their children in the UK when Russia invaded Ukraine, and have been living with one daughter in Surrey under a family visa.

He describes the welcome he has received as "beautiful". "It's been amazing that we've been really welcomed," he says.

Problems with job checks

With Ukrainians searching for work in the UK, the issue of obtaining safeguarding checks for certain jobs has arisen.

Speaking to BBC Radio 5 Live, former MP Edwina Currie says a Ukrainian woman she is hosting applied for a job at her children's school.

"[She] was promptly told that because they couldn't check her [Disclosure and Barring Service] status… she couldn't be considered for the job."

Edwina says it "needs sorting out" so those arriving can take work opportunities in places like schools.

"Many of the people looking for work are mothers with young children, it will suit them for example to be working in school kitchens."

Some 82% of Ukrainians arriving in the UK were female and 48% reported that they had at least one dependent child to the ONS survey conducted in April.

Ukrainian refugees are able to apply for criminal records checks and guidance is offered to make the process "more accessible", the Home Office says.

Work coaches, training programmes specialising in the hospitality and agriculture sector and language courses are among the support being offered to Ukrainian refugees, the Department for Work and Pensions adds.

- Published4 July 2022

- Published21 July 2022

- Published4 May 2022