SAS unit repeatedly killed Afghan detainees, BBC finds

- Published

SAS troops conducted night raids in Afghanistan, aiming to kill or capture Taliban targets

SAS operatives in Afghanistan repeatedly killed detainees and unarmed men in suspicious circumstances, according to a BBC investigation.

Newly obtained military reports suggest that one unit may have unlawfully killed 54 people in one six-month tour.

The BBC found evidence suggesting the former head of special forces failed to pass on evidence to a murder inquiry.

The Ministry of Defence said British troops "served with courage and professionalism in Afghanistan".

The BBC understands that General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith, the former head of UK Special Forces, was briefed about the alleged unlawful killings but did not pass on the evidence to the Royal Military Police, even after the RMP began a murder investigation into the SAS squadron.

General Carleton-Smith, who went on to become head of the Army before stepping down last month, declined to comment for this story.

BBC Panorama analysed hundreds of pages of SAS operational accounts, including reports covering more than a dozen "kill or capture" raids carried out by one SAS squadron in Helmand in 2010/11.

Individuals who served with the SAS squadron on that deployment told the BBC they witnessed the SAS operatives kill unarmed people during night raids.

They also said they saw the operatives using so-called "drop weapons" - AK-47s planted at a scene to justify the killing of an unarmed person.

SAS Death Squads Exposed: A British War Crime?

British special forces killed hundreds of people on night raids in Afghanistan, but were some of the shootings executions? BBC Panorama's Richard Bilton uncovers new evidence and tracks down eyewitnesses.

Several people who served with special forces said that SAS squadrons were competing with each other to get the most kills, and that the squadron scrutinised by the BBC was trying to achieve a higher body count than the one it had replaced.

Internal emails show that officers at the highest levels of special forces were aware there was concern over possible unlawful killings, but failed to report the suspicions to military police despite a legal obligation to do so.

The Ministry of Defence said it could not comment on specific allegations, but that declining to comment should not be taken as acceptance of the allegations' factual accuracy.

An MOD spokesperson said that British forces "served with courage and professionalism" in Afghanistan and were held to the "highest standards".

SAS killings in Afghanistan: The story of one suspicious death

A pattern of suspicious killing

In 2019, the BBC and the Sunday Times investigated one SAS raid which led to a UK court case and an order to the UK defence minister to disclose documents outlining the government's handling of the case.

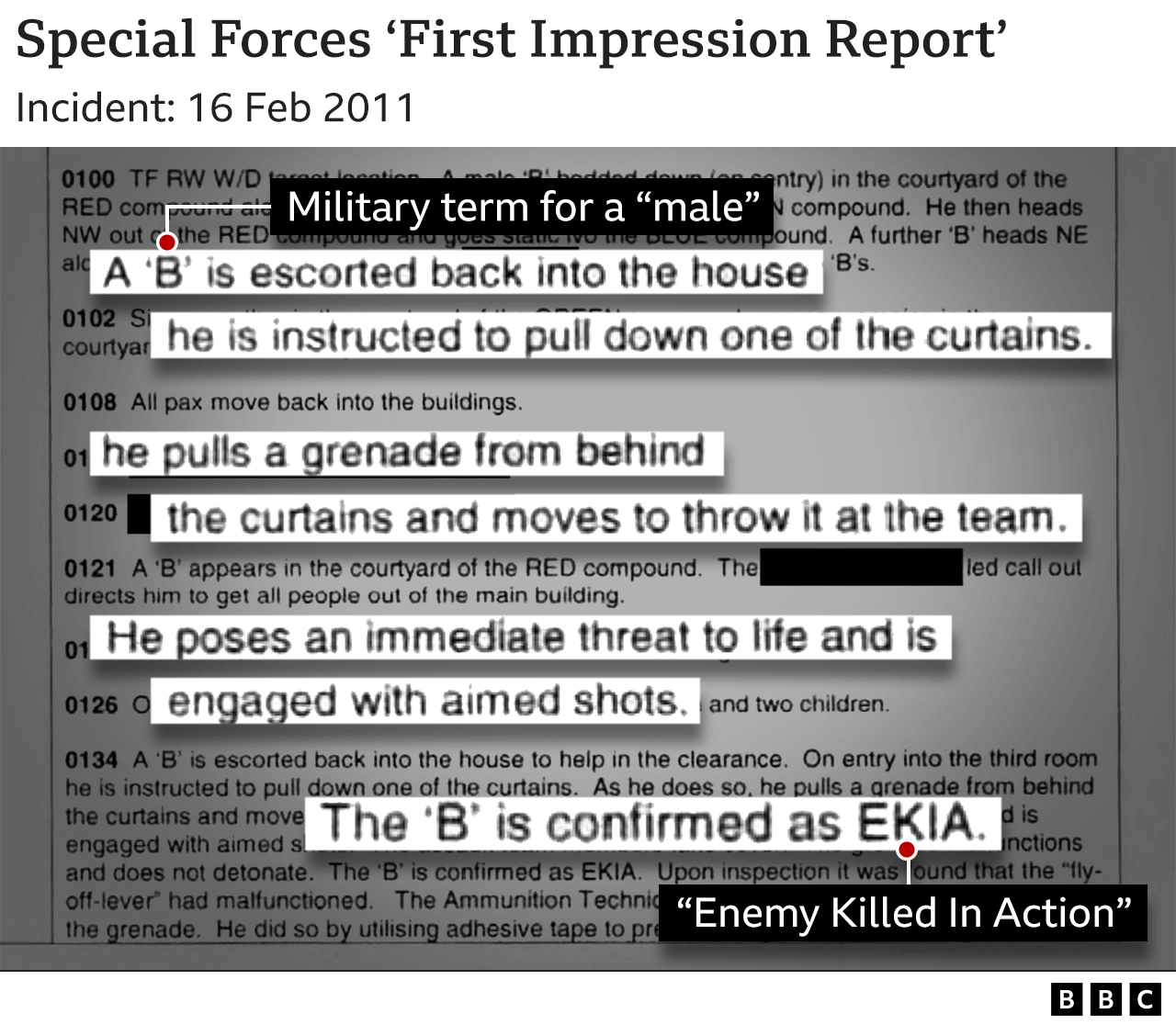

For this latest investigation, the BBC analysed newly obtained operational reports detailing the SAS's accounts of night raids. We found a pattern of strikingly similar reports of Afghan men being shot dead because they pulled AK-47 rifles or hand grenades from behind curtains or other furniture after having been detained.

On 29 November 2010, the squadron killed a man who had been detained and taken back inside a building, where he "attempted to engage the force with a grenade".

On 15 January 2011, the squadron killed a man who had been detained and taken back inside a building, where he "reached behind a mattress, pulled out a hand grenade, and attempted to throw it".

On 7 February, the squadron killed a detainee who they said had "attempted to engage the patrol with a rifle". The same justification was given for the fatal shooting of detainees on 9 February and 13 February.

On 16 February, the squadron killed two detainees after one pulled a grenade "from behind the curtains" and the other "picked up an AK-47 from behind a table".

On 1 April, the squadron killed two detainees who had been sent back inside a building after one "raised an AK-47" and the other "tried to throw a grenade".

The total death toll during the squadron's six-month tour was in the triple figures. No injuries to SAS operatives were reported across all the raids scrutinised by the BBC.

A senior officer who worked at UK Special Forces headquarters told the BBC there was "real concern" over the squadron's reports.

"Too many people were being killed on night raids and the explanations didn't make sense," he said. "Once somebody is detained, they shouldn't end up dead. For it to happen over and over again was causing alarm at HQ. It was clear at the time that something was wrong."

Internal emails from the time show that officers reacted with disbelief to the reports, describing them as "quite incredible" and referring to the squadron's "latest massacre". An operations officer emailed a colleague to say that "for what must be the 10th time in the last two weeks" the squadron had sent a detainee back into a building "and he reappeared with an AK".

"Then when they walked back in to a different A [building] with another B [fighting-age male] to open the curtains he grabbed a grenade from behind a curtain and threw it at the c/s [SAS assault team]. Fortunately, it didn't go off…. this is the 8th time this has happened... You couldn't MAKE IT UP!"

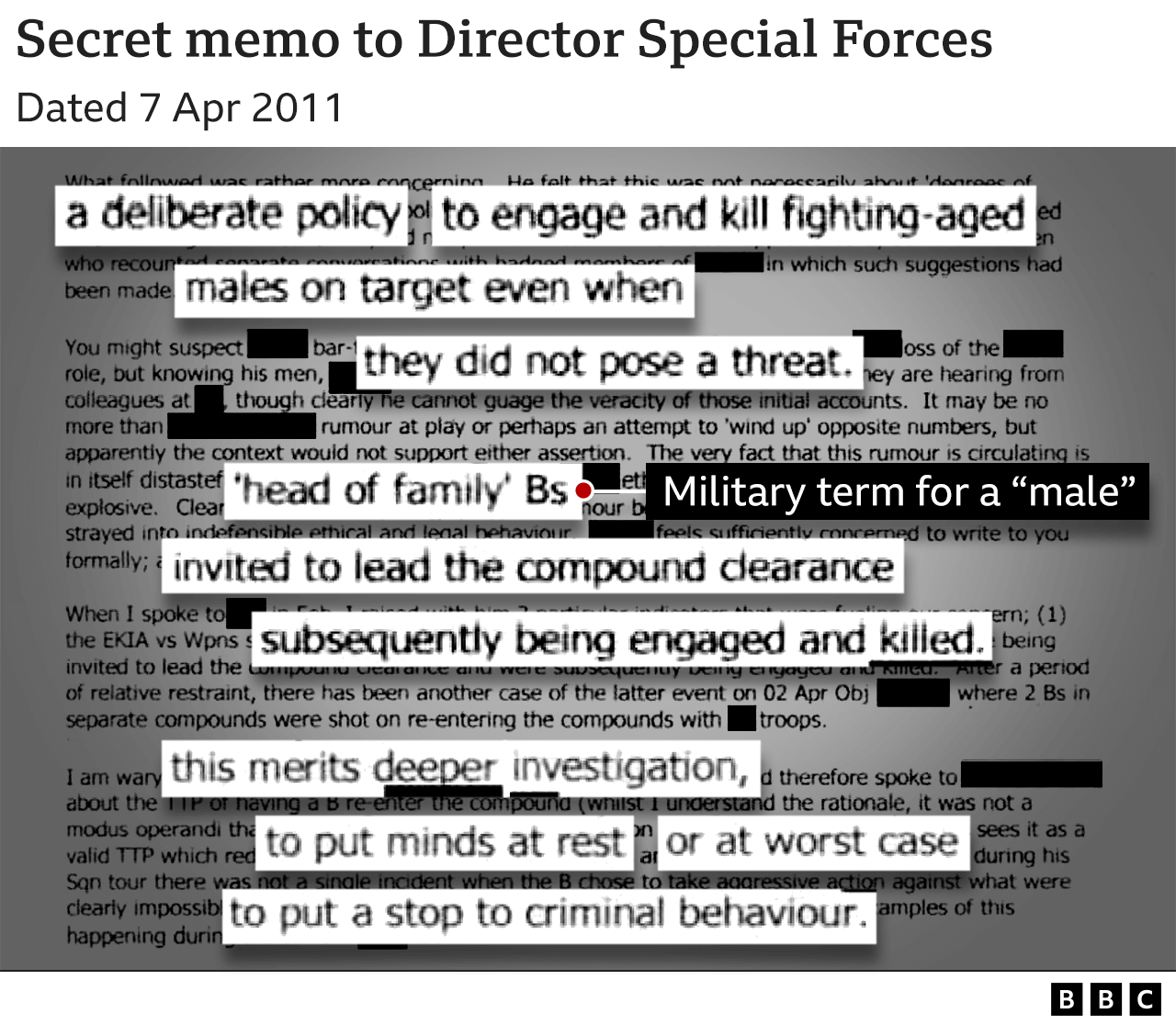

As the concerns grew, one of the highest-ranking special forces officers in the country warned in a secret memo that there could be a "deliberate policy" of unlawful killing in operation. Senior leadership became so concerned that a rare formal review was commissioned of the squadron's tactics. But when a special forces officer was deployed to Afghanistan to interview personnel from the squadron, he appeared to take the SAS version of events at face value.

The BBC understands that the officer did not visit any of the scenes of the raids or interview any witnesses outside the military. Court documents show that the final report was signed off by the commanding officer of the SAS unit responsible for the suspicious killings.

None of the evidence was passed on to military police. The BBC discovered that statements containing the concerns were instead put into a restricted-access classified file for "Anecdotal information about extrajudicial killings", accessible only to a handful of senior special forces officers.

In 2012, General Carleton-Smith was appointed head of UK special forces. The BBC understands that he was briefed about the suspicious killings, but he allowed the squadron to return to Afghanistan for another six-month tour.

When the Royal Military Police launched a murder investigation in 2013 into one of the raids conducted on that tour, General Carleton-Smith did not disclose to the RMP any of the earlier concerns over unlawful killings, or the existence of the tactical review.

Colonel Oliver Lee, who was commander of the Royal Marines in Afghanistan in 2011, told the BBC that the allegations of misconduct raised by our investigation were "incredibly shocking" and merited a public inquiry. The apparent failure by special forces leadership to disclose evidence was "completely unacceptable", he said.

General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith was head of UK Special Forces when military police investigated the SAS in 2013

Kill or capture

The BBC's investigation focused primarily on one six-month deployment by one SAS squadron that arrived in Afghanistan in November 2010.

The squadron was operating largely in Helmand province, one of the most dangerous places in Afghanistan, where Taliban ambushes and roadside bombs were common and Army losses were high.

The squadron's primary role was carrying out deliberate detention operations (DDOs) - also known as "kill or capture" raids - designed to detain Taliban commanders and disrupt bomb-making networks.

Read more: SAS killings: How a scandal was uncovered

Watch Panorama: SAS Death Squads Exposed: A British War Crime?

Watch the investigation from 2019: War Crimes Scandal Exposed

Several sources who were involved in selecting targets for special forces operations told the BBC that there were grave problems with the intelligence behind the selection process, meaning civilians could easily end up on a target list.

According to a British representative who was present during target selection in Helmand in 2011, "Intelligence guys were coming up with lists of people that they figured were Taliban. It would be put through a short process of discussion. That was then passed onto special forces who would be given a kill or capture order."

According to the source, the targeting was pressured and rushed. "It didn't necessarily translate into let's kill them all, but certainly there was a pressure to up the game, which basically meant passing out judgements on these people quickly," he said.

Sources told the BBC that the targeting process for night raids was often rushed and could mislabel innocent civilians

During the raids, the SAS squadron used a recognised tactic in which they called everyone from inside a building out, searched and restrained them with cable-tie handcuffs, then took one male back inside to assist special forces operatives with a search.

But senior officers became concerned by the frequency with which the squadron's own accounts described detainees being taken back inside buildings and then grabbing for hidden weapons - an enemy tactic not reported by other British military forces operating in Afghanistan.

There were also concerns among officers that on a significant number of raids, there were more people killed than weapons reportedly recovered from the scene - suggesting the SAS was shooting unarmed people - and that SAS operatives might be falsifying evidence by dropping weapons at scenes after killing people.

After similar concerns were raised in Australia, a judge-led inquiry was commissioned and found "credible evidence" members of Australian Special Forces were responsible for the unlawful killing 39 people, and used 'drop weapons' in an attempt to justify shootings.

By April 2011, the concerns were so great in the UK that a senior special forces officer wrote to the director of special forces warning that there was evidence of "deliberate killing of individuals after they have been restrained" and "fabrication of evidence to suggest a lawful killing in self-defence".

Two days later, the UK Special Forces assistant chief of staff warned the director that the SAS could be operating a policy to "kill fighting-aged males on target even when they did not pose a threat."

If the suspicions were true, he wrote, the SAS squadron had "strayed into indefensible ethical and legal behaviour".

The SAS squadron operated in some of the most dangerous areas in southern Afghanistan, often raiding residential compounds in villages

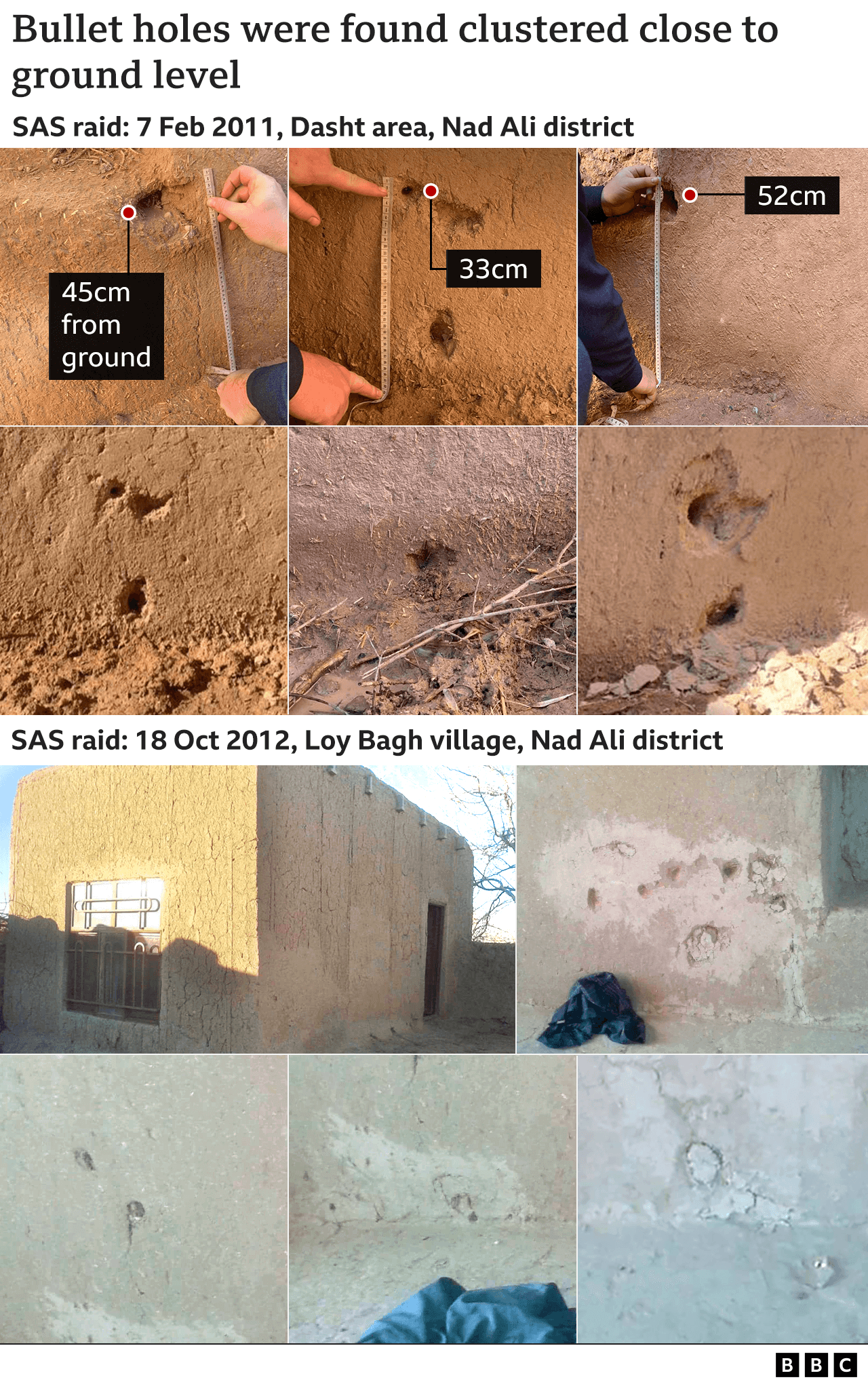

The BBC visited several of the homes raided by the SAS squadron in 2010/11. At one, in a small village in Nad Ali in Helmand, there was a bricked up guesthouse where nine Afghan men including a teenager were killed in the early hours of 7 February 2011.

The SAS operatives arrived in helicopters under the cover of darkness and approached the house from a nearby field. According to their account, insurgents opened fire at them, prompting them to shoot back and kill everyone in the guesthouse.

Only three AK-47s were recovered, according to the SAS account - one of at least six raids by the squadron on which the reported number of enemy weapons was fewer than the number of people killed.

Inside the guesthouse, what appeared to be bullet holes from the raid were clustered together on the walls low to the ground. The BBC showed photographs from the scene to ballistics experts, who said that the clusters suggested multiple rounds had been fired downward from above, and did not appear indicative of a firefight.

Leigh Neville, an expert on weapons used by UK Special Forces, said the bullet patterns suggested that "targets were low to the ground, either prone or in a sitting or crouching position close to the wall - an unusual position if they were actively involved in a firefight".

The same pattern was visible at two other locations examined by the BBC. Ballistics experts who reviewed images said the bullet holes were suggestive of execution-style killings rather than firefights.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, an RMP investigator confirmed to the BBC that they had seen photographs from the scenes and that the bullet mark patterns had raised alarm.

"You can see why we were concerned," the investigator said. "Bullet marks on the walls so low to the ground appeared to undermine the special forces' version of events."

In 2014, the RMP launched Operation Northmoor, a wide-ranging investigation into more than 600 alleged offences by British forces in Afghanistan, including a number of killings by the SAS squadron. But RMP investigators told the BBC that they were obstructed by British military in their efforts to gather evidence.

Operation Northmoor was wound down in 2017 and eventually closed in 2019. The Ministry of Defence has said that no evidence of criminality was found. Members of the investigations team told the BBC they dispute that conclusion.

The Ministry of Defence said British troops were held to the highest standards. "No new evidence has been presented, but the Service Police will consider any allegations should new evidence come to light," a spokesperson said.

In a further statement, the MoD said it believed Panorama had jumped to "unjustified conclusions from allegations that have already been fully investigated".

It said: "We have provided a detailed and comprehensive statement to Panorama, highlighting unequivocally how two Service Police operations carried out extensive and independent investigation into allegations about the conduct of UK forces in Afghanistan.

"Neither investigation found sufficient evidence to prosecute. Insinuating otherwise is irresponsible, incorrect and puts our brave Armed Forces personnel at risk both in the field and reputationally.

"The Ministry of Defence of course stands open to considering any new evidence, there would be no obstruction. But in the absence of this, we strongly object to this subjective reporting."

- Published12 July 2022

- Published12 July 2022

- Published1 August 2020