In her own words - Molly Russell's secret Twitter account

- Published

Unsafe online content contributed "in a more than minimal way" to the death of 14-year-old Molly Russell, an inquest found on Friday.

Early in the inquest it was revealed that Molly - who took her own life in 2017 - had a secret Twitter account which she used to express her thoughts about her worsening depression.

The BBC learnt about the account several years ago, and the Russell family hope publicising it now will help others.

After her death, Molly became a household name - a photo of her in school uniform appeared across newspaper front pages - as her father became a prominent campaigner for stronger regulation of social media.

Ian believes most of Molly's time online was spent on Instagram and Pinterest, where she viewed thousands of images concerning suicide and self harm.

Representatives of both companies gave evidence at her inquest. Molly spent much less time on Twitter, and the company was not involved in the inquest.

But nevertheless, the time she spent on the platform is significant - because we can see her own thoughts and feelings, written and composed as tweets, and how complex and nuanced a teenager's mental health can be.

This article was first published on 21 September.

Information and support

If you are suffering distress or despair, details of help and support are available here.

The Met Police forensically examined Molly's phone in preparation for the inquest. Officers handed over tens of thousands of pages of material to the Russell family's legal team, including details of the previously-unknown Twitter account.

The account revealed that for a year, Molly expressed her state of mind through a series of tweets and retweets.

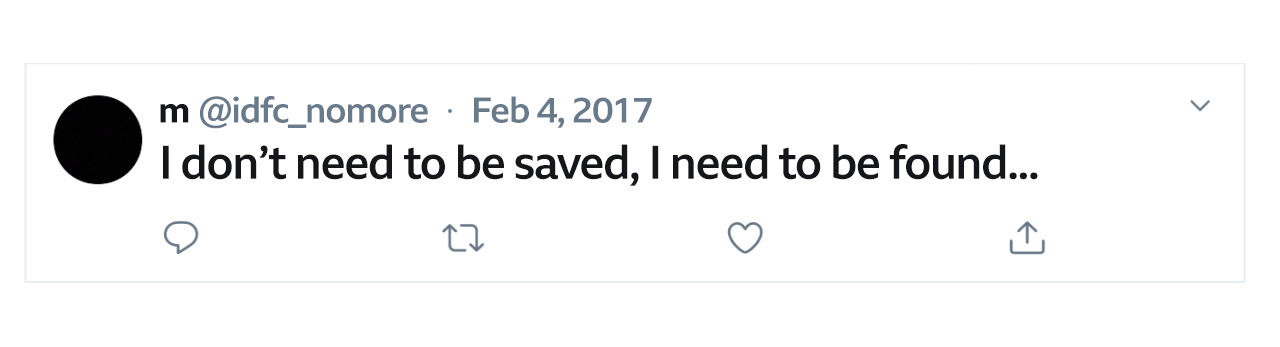

The name she chose for her Twitter handle was "Idfc_nomore," which Ian thinks meant, "I don't care no more," with an expletive in the middle.

But normal teenage interests are reflected by what she wrote in her Twitter bio - a short "about me" summary at the top of her account. It read: "Harry Potter is life."

Ian has locked the account so others cannot view Molly's tweets, but he is happy for us to quote them.

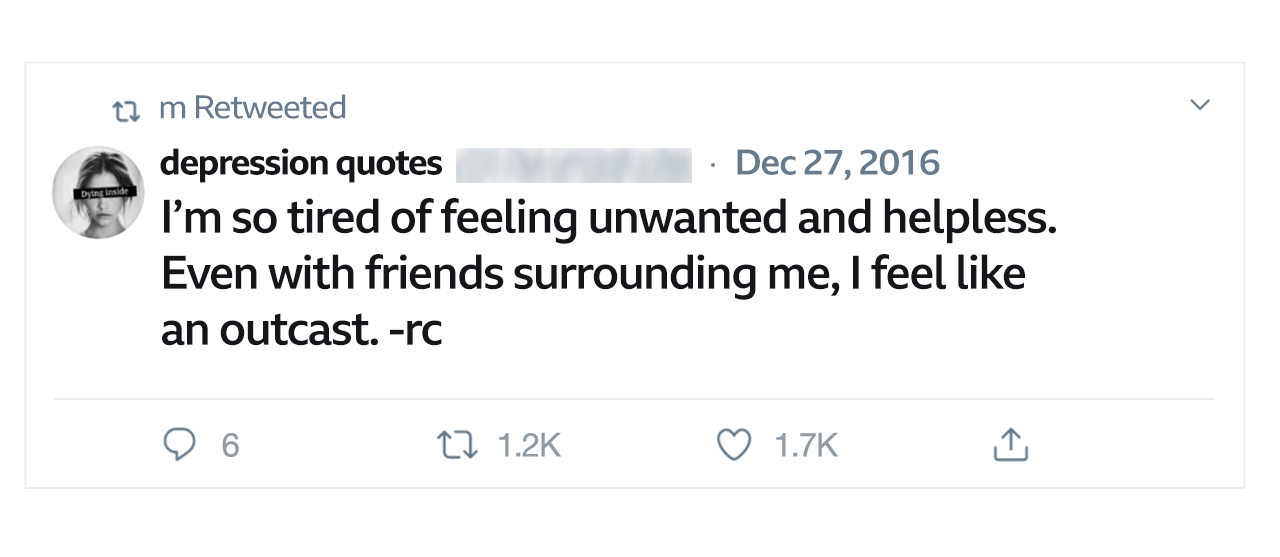

She first tweeted in December 2016, sharing a post by an account dedicated to tweeting quotes about depression.

That account has been on Twitter for years, with more than 200,000 followers. It appears to belong to an American teenage boy who has struggled with depression, self-harm and anxiety - a US suicide hotline number is "pinned" to the top of the account, so people will see it before starting to scroll down.

Like many similar accounts, its bio contains the term, "Trigger Warning - proceed with caution".

When Molly followed this account, Twitter's algorithms would have recommended similar ones - the more you interact with content on a particular subject, the more of that kind of content is suggested to you.

Twitter told us its number one priority was the safety of people who used its service. A spokesman said it has forged partnerships with UK mental health authorities to offer vulnerable people a support service called #ThereIsHelp, which provides mental health resources.

"As a result of this partnership, when someone searches for terms associated with suicide or self harm, the top search result is a notification encouraging them to reach out for help," he added.

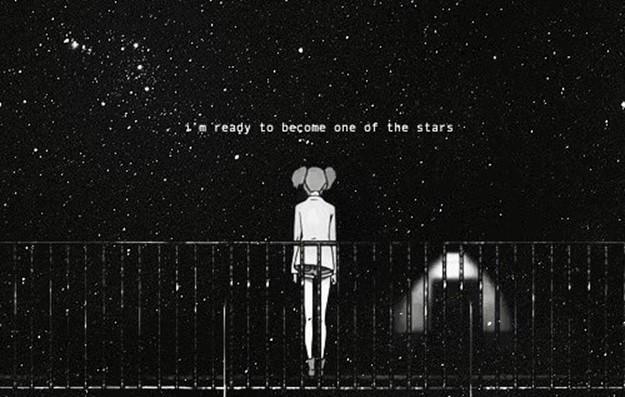

The first picture Molly retweeted using her secret account was a hand-drawn image of a teenage girl staring at the night sky, saying, "I'm ready to become one of the stars".

The first image tweeted by Molly

Teenagers may search for such content because they are feeling troubled and want to reach out to others. We are conscious of not wanting to direct vulnerable teenagers toward content of this kind, but they already follow these accounts in their tens of thousands - which Ian believes is incredibly dangerous.

Ian says such images dress up suicide, and the grief it causes, in a way that makes it almost acceptable.

"There's a sort of stylistic, artistic, creative way that says, 'join this, join this club,'" he says.

The charity Papyrus specialises in suicide prevention for young people. It estimates four children aged five to 18 end their own lives in the UK each week.

Calls to its helpline surged when Molly's story hit the headlines, with more than 30 families saying they felt social media had played a role in their child's death.

Its chief executive, Ged Flynn, says struggling with suicidal thoughts over a long period of time is not unusual.

"They will go over and over their thoughts, ruminate and cogitate sometimes for weeks and months," he says. "Many young people do that online - exercising their uncertainty, trying to work it out, asking, 'Am I the only one to feel like this?'

"People don't wear a big sign around their neck that they need help. They will drop hints and Molly was doing that online."

Advice for parents, carers and guardians

Talking to your child about suicidal thoughts can be difficult and feel very daunting, says the charity Papyrus, external, but starting the conversation is the most important thing.

It suggests these simple steps may help you discuss the issue with your child:

Ask directly

Use the word suicide

Practice asking first if this helps - it may give you more confidence

Stay calm - this is important as your child may be looking at how you react before deciding how much they should tell you

Be clear and direct

Look them in the eye and ask: "Are you thinking about suicide?"

For months, if not years, it seemed Molly was able to hide her depression from those who knew her.

Ian remembers a time when she had not quite been herself. During a car journey he spoke to her about it and made her promise to tell him if there was ever something she needed to talk about. She agreed.

But Molly chose Twitter and Instagram instead.

She wrote on Twitter for the first time on 4 February 2017: "I don't need to be saved, I need to be found." This came from a poem by the model and actress Cara Delevingne, about her own struggle with depression.

A day later, Molly tweeted this, apparently a screenshot from her own Pinterest account:

"It just shows the depth of despair she must have been feeling, which none of us had any idea," Ian says. "I think she thought she was coping, she was finding a way through it. And then, slowly over those months, it all grew - and it swamped, consumed her. But she kept this secret."

In between her growing depression, Molly also shared the interests of an ordinary teenager on her Twitter account. She stayed up late waiting for a video to drop from US rapper Phora. She watched the American TV drama Riverdale. She retweeted Ariana Grande around the time of the Manchester terror attack.

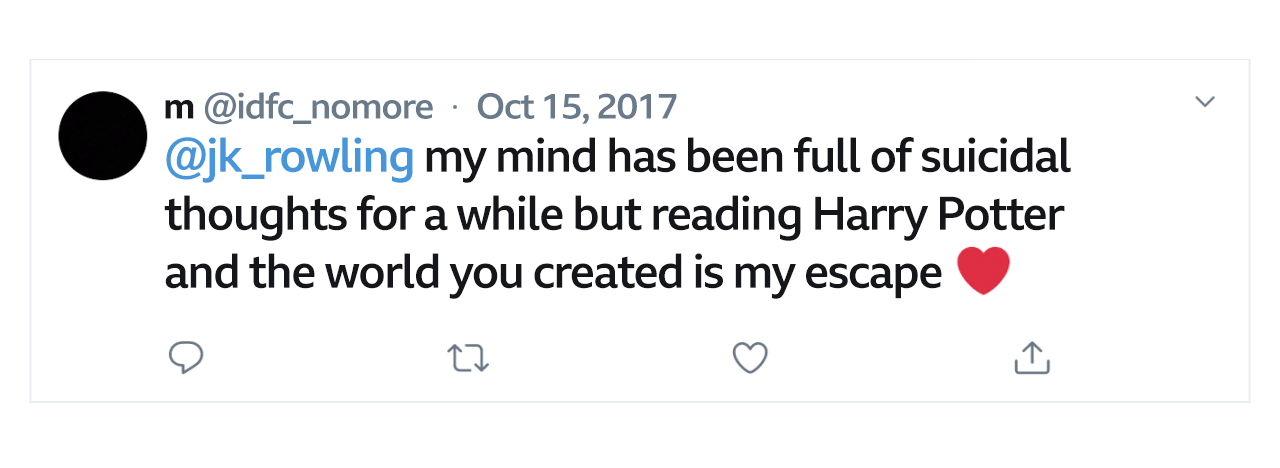

But, at the same time, Molly sent a tweet to JK Rowling saying her mind was full of suicidal thoughts. She didn't get a reply, but that is not surprising given the author has 13.9 million followers and must receive countless mentions and messages.

Some of Molly's activity suggests she was looking for help, but did not quite know where to find it.

One of the stars of Riverdale, Lili Reinhart, has publicly struggled with depression. During mental health awareness month in 2017, Reinhart, who has more than three million followers, tweeted urging them to have strength.

"When I'm feeling depressed or sad, I remind myself how far I've come," she wrote, "and how I didn't let depression consume me."

Molly retweeted the posts but also messaged Reinhart directly, saying: "I can't take it no more, I need someone but I can't reach out to anyone I love I just can't take it."

She did not receive a reply. Like JK Rowling, Reinhart has millions of followers and must equally be inundated with messages.

Molly would later tweet a link to an online TED talk from California Highway Patrol Officer, Kevin Briggs. In it, he shared his experiences of trying to talk to people in moments of personal crisis, when they were about to jump from bridges.

It is clear from her tweets that Molly was struggling. She was depressed and, it seems, increasingly focused on taking her own life.

On 19 July, she posted words of despair on Twitter:

But instead of talking to her family or friends, Molly discovered a Californian influencer who most people in the UK will probably never have heard of.

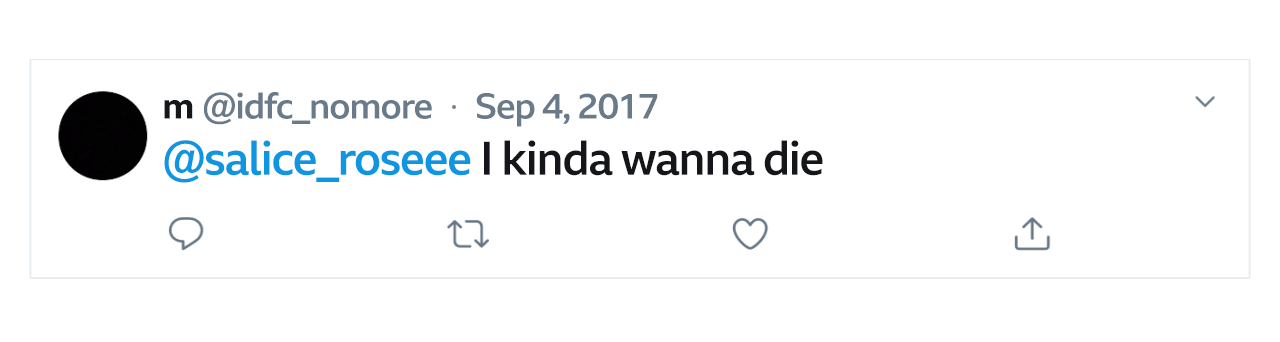

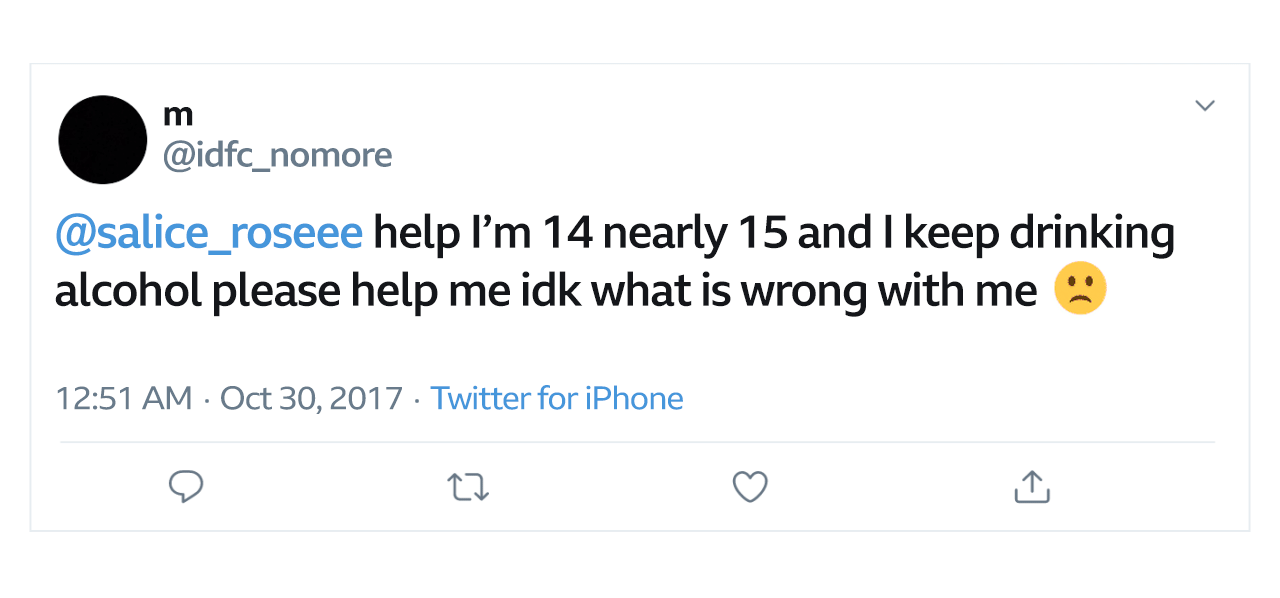

Salice Rose has a fanbase of millions on Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and more recently TikTok. Molly messaged her repeatedly.

Despite outwardly appearing confident and full of life, Rose has publicly struggled with her own depression and anxiety.

Was this what drew a teenager from Harrow, in north-west London, to her?

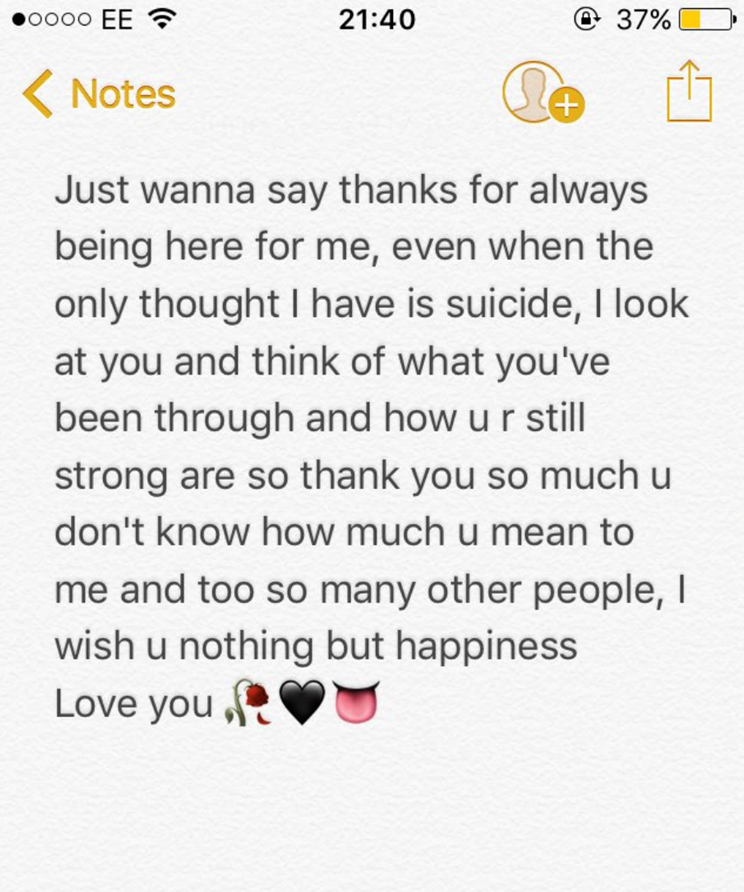

On her phone, it appears as though Molly had composed a note to the influencer thousands of miles away:

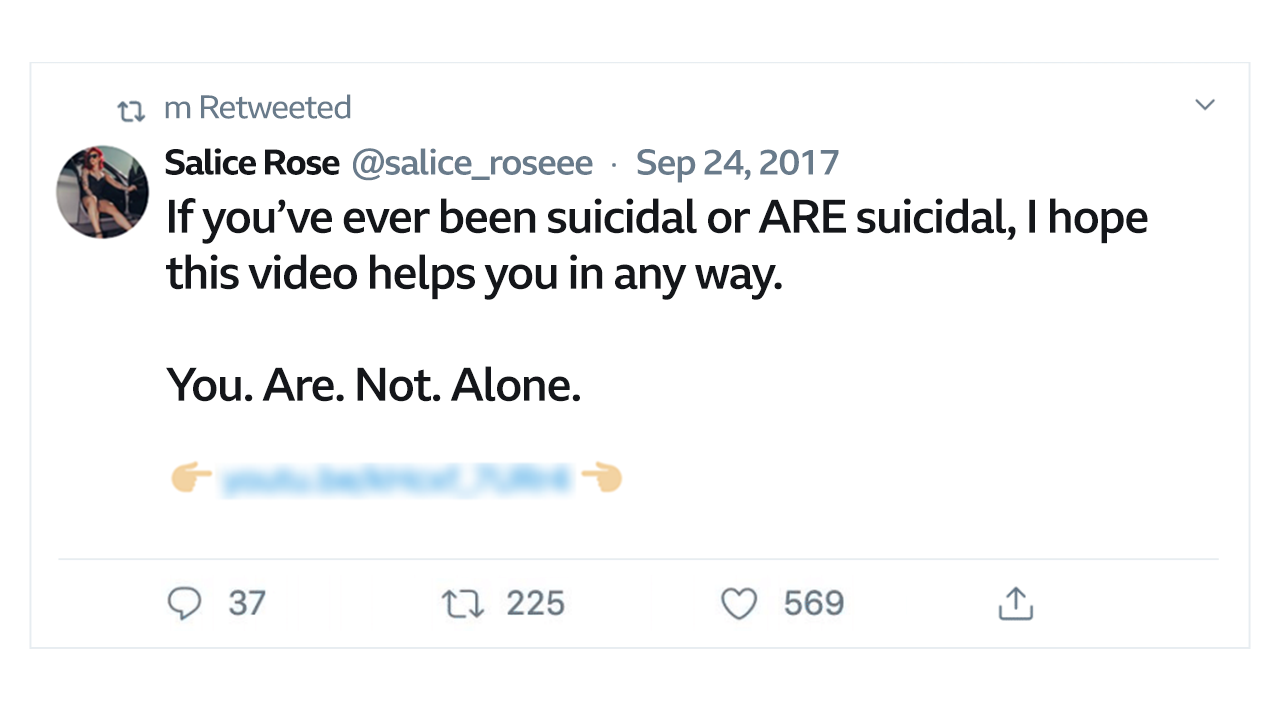

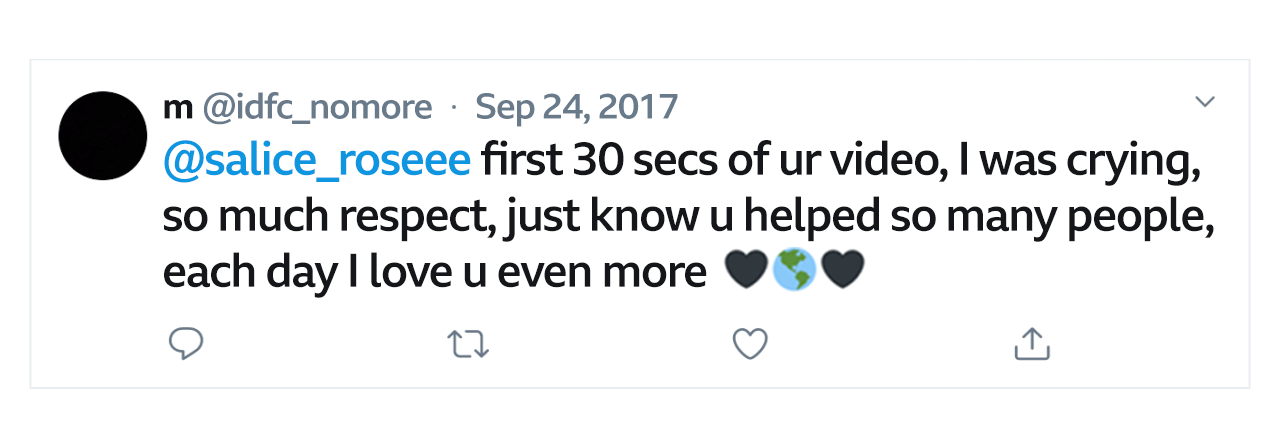

And Molly was clearly moved when Salice Rose posted a dramatic video advising how to overcome suicidal thoughts.

She repeatedly tweeted Rose asking for help, but did not receive a reply.

Ged Flynn from Papyrus says celebrities must be socially responsible. He says it is important to share and normalise the fact that life is difficult, but they must balance this by showing that help is available and where to get it.

"If I send you an email I may expect a response. For a young person like Molly, that expectation may be heightened. They've seen someone putting out their pain and they want to connect with that person," he says.

Molly's father Ian thinks his daughter believed Salice had been reading and answering messages more than would have been physically possible. "By being able to shout into the vast world of the internet, Molly had the false impression that she was being listened to when, in effect, she was just shouting into the wind," he says.

Salice Rose sent a video statement to the BBC saying she was upset that she did not know who Molly was, because if she did she could have called her and told her not to end her life.

"It's a feeling of guilt, knowing that one of my followers ended their life because in that moment, I could have helped… and I'm trying my hardest not to cry, because this isn't about me, it's about Molly. It's super sad and she will always be in my prayers," she said.

For Ian, Molly's tweets make hard reading. One showed his daughter was on her phone at 01:00, talking about drinking alcohol.

He says Molly's entire family wishes every day that they had realised how she had been feeling and had done something different.

"Part of learning to process the grief that comes with a death by suicide is also learning to deal with that guilt. Many nice people say you can't blame yourself but that's an impossibility.

"Some days are worse than others. But I don't think there will be a day in the rest of my life where I won't blame myself."

Looking at her tweets, it is clear that, at the end of September 2017, Molly's mood was darkening again. She messaged the US rapper Phora, who has 380,000 followers.

Unfortunately, says Ged Flynn, Molly was looking for help in the wrong places. "At its simplest, that a person is still alive and tweeting is an opportunity for someone to step in. We need young people to sometimes look for adult help, expert help and most importantly safe help."

Ian agrees. "If you're in a horrible low place where you actually want to end your life, please reach out to those people you love."

To Molly's parents, everything appeared normal. They had no idea that anything was wrong.

In the week before her death, Molly won a part in a school play and appeared to be looking forward to rehearsals. There was also a family celebration for her sisters' birthdays coming up.

On Monday 20 November, she completed her homework, packed her school bag and watched TV with her family. Ian remembers that evening well - they were watching the new series of "I'm a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here".

Sitting next to him on the sofa, Molly was on Twitter on her phone. She wished Salice Rose a happy birthday - these are her last words on the platform:

Everything appeared normal. Yet, for a reason only she will ever know, Molly took her own life in the early hours of the following morning.