Princess Anne: The can-do will-do royal

- Published

The Princess Royal, observing her late mother's coffin

There is one great final duty that many children feel towards their parents: the duty to see them safely and peacefully to their last rest.

Almost all who take on that emotional task do so out of the public glare.

But it was always going to be different for Princess Anne amid an extraordinary moment of history.

In the last few days, it's emerged that the late Queen wished that her only daughter, officially the Princess Royal, should take the primary role in escorting her coffin - an echo of the role she herself played for her father King George VI's final journey from Sandringham in 1952.

Her wish reflects the princess's reputation for hard work and duty, and the practical burdens faced by King Charles in the first days of his reign.

Within 24 hours of Elizabeth's death, the new king's life had become a whirlwind, requiring him to balance personal grief with his duties of state.

His 72-year-old sister - younger by 21 months - was at Balmoral, preparing to escort the Queen's coffin from that private family space into the public realm.

The first stage was to accompany the coffin on its six-hour journey to the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

The long road from Balmoral: The Princess Royal's car following the hearse in Scotland

The journey would have required a degree of stoicism. By the time she had performed a deep curtsey as the coffin was carried into the Edinburgh palace, the emotion was showing.

On Monday, her duties continued. This time, she walked behind the pallbearers to St Giles' Cathedral. Later, at the lying-in-rest, the princess became the first female member of the Royal Family to take part in the traditional vigil.

Princess Anne curtseys as her mother's coffin is brought to Edinburgh

The symbolism and message of Anne, standing solemnly in her honorary Royal Navy ceremonial uniform, was clear. Here was a princess raised in the modern era: an equal to her brothers.

On Tuesday evening she accompanied the coffin, on the farewell to Scotland, escorting it all the way to Buckingham Palace, where the full protocol and formalities of a state funeral would begin.

Nobody should be surprised by the prominent role of Princess Anne. She is hardly someone to baulk at duty and service.

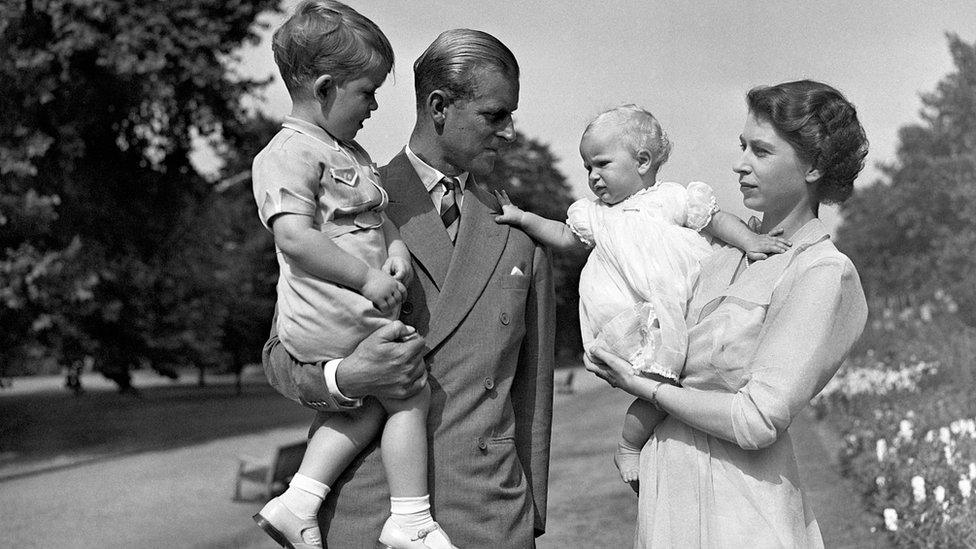

Charles and Anne, less than two years between them, with their parents

For years, she and Charles have been measured by watchers for the annual title of Most Hardworking Royal.

In 2021 she undertook 387 official engagements - two more than the then-Prince of Wales - a number that had been growing for both of them in the later years of her mother's reign.

She has completed almost 500 overseas visits - 49 to Germany alone - and is patron of a 300 charities. Her association with Save The Children dates back to 1970.

Even during the pandemic she was at work, visiting and raising the profile of a mobile testing centre.

As her public presence developed over the decades, it was clear she had inherited her late father's reputation for no-nonsense and, on occasion, blunt-speaking.

That dogged refusal to play the role of a meek fairy tale princess stood her in good stead during a botched 1974 attempt to kidnap her.

She recalled to TV chat show host Michael Parkinson her refusal to go with the kidnapper amid the shoot-out which had left her protection officer and two others wounded,

"We had a discussion about where - or where not - we were going to go," she recalled. "I was scrupulously polite because I thought it would be silly to be too rude at that stage."

An official government report available at the National Archives reports that her actual words to the assailant had been: "Not bloody likely."

Her formal title of Princess Royal is a customary honour dating from the 17th Century. Notwithstanding that tradition, its award in 1987 has long been considered a symbol of how her work was so valued within what her parents - and grandfather King George VI - called "The Firm".

That hard work has long been balanced with an independence of spirit - often difficult to achieve as a working Royal.

Competing in horse trials in 1976, the year she made the Olympic squad

In 1971, the then-21-year-old took the gold medal at the European eventing championships - and she was named BBC Sports Personality Of The Year. Five years later she made the Team GB for the Montreal Olympics.

"I certainly saw it as a way of proving that you had something that was not dependent on your family," she later said. "It was down to you to succeed or fail."

Clearly, she had that approach to life in mind when she passed her heavy goods vehicle test, allowing her to drive horse lorries without the help of a royal retinue.

As competitive equine sports receded with age, other work that brought her personal satisfaction took over - including overseeing her Gloucestershire farm.

When she guest-edited Country Life magazine for her 70th birthday, she critiqued what had gone wrong in some rural areas - calling for more to be done to provide housing for local people who are "priced out of the market".

"All of them could make the difference," she wrote, external.

When Charles, as Prince of Wales, spoke his mind, his interventions regularly raised constitutional eyebrows.

For Anne-watchers it was more a mark of a practical solutions-focused woman who has spent her life wanting to get things done - so focused on getting things done that she raised her own children without royal titles, in the hope that they could have a relatively normal life.

That can-do will-do attitude will continue to be seen in the days ahead - an attitude first seen in September 1969.

Back then, just 18-years-old, she undertook her first official engagement for Queen Elizabeth, when she opened a double-decker bus training centre near Shrewsbury.

The Birmingham Post reported she was a "most modern Miss", taking to the wheel of an Albion Viking bus and laughing that it was easier to handle than a Balmoral Land Rover.

It was the first of thousands of duties on behalf of Queen Elizabeth.

Her last duties for her late mother are now before her.

The princess herself says it has been an "honour and a privilege" to accompany her mother on her final journeys.

There is no doubt that a new chapter in her public life is about to begin as she counsels and supports the King - and carries on rolling up her sleeves and getting on with it.