Three PMs in two months, is political chaos the UK's new normal?

- Published

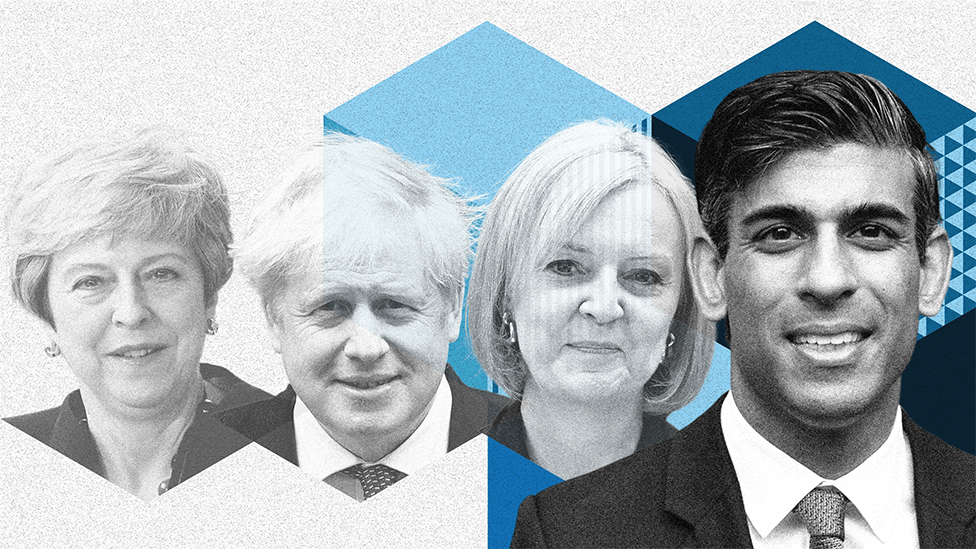

Rishi Sunak is the UK's third prime minister in less than two months - the fifth in six years. It is the fastest turnover of leaders in No 10 for nearly a century.

Since the summer of 2007, Gordon Brown, David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Mr Sunak have all held the top office. In contrast, there were just three prime ministers in the 28 years before - Margaret Thatcher, John Major and Tony Blair.

What is the cause of the revolving door at No 10? And could this trend be the new normal for British politics?

A panel of experts share their thoughts on why it appears increasingly difficult for prime ministers to remain in power.

Jill Rutter, from the think tank the Institute for Government, believes the Brexit vote in 2016 has been the number one destabilising factor in British politics over the last six years.

"We can attribute almost all of the instability to a fallout of the Brexit referendum and what it has done to the Conservative Party," she says.

"David Cameron was a long-serving prime minister. Had he not had the referendum, he could have been on track till 2018 and would have handed over to either George Osborne or Boris Johnson.

"He was derailed by calling the referendum. It was a tactical error not to go all-out for the victory and thinking victory was in the bag," she adds.

Mr Cameron's resignation after six years in office paved the way for Theresa May. She spent three years and 11 days in office, while her successor, Boris Johnson, spent three years and 44 days at the helm.

"Theresa May was clearly brought trouble by a twin combination - the disastrous election in 2017 and the fact that she and the party could not agree what Brexit meant," Ms Rutter adds.

She says the Conservative Party "thought Boris Johnson could break the Brexit deadlock, but one of the ways he did that was by not paying much attention to norms and rules".

"It was his failure to do this that brought him down. It meant his ministers could not take it anymore. They'd gone for somebody in desperation."

Liz Truss's shorter premiership at barely seven weeks was, according to Ms Rutter, a direct legacy of the referendum.

"The membership had changed quite a bit," she explains. "They were ready for the message about ignoring orthodoxy. But they discovered when they went hell for leather against conventional wisdom, they fell over in a heap."

Vernon Bogdanor, professor of government at King's College in London, agrees.

"The referendum has destabilised British politics," he says. "The difficulty has been to find the right relationship with Europe."

But is it really all about Brexit?

Tim Bale, professor of politics at Queen Mary University, believes the trend could be something that runs much deeper.

He points to what he calls the "presidentialisation" of the UK's parliamentary system, or the greater focus on party leaders, as one of the reasons that prime ministers' terms are not lasting as long.

"There is far more focus from voters and politicians on party leaders and rather less on the party as a whole - that means that the leader is often held personally responsible for anything that goes wrong," he says.

"It is now pretty much impossible for a party leader to lead his or her party [after] an election defeat," he explains, adding that former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was the notable exception to the rule in 2017.

Aged 42, Rishi Sunak is the youngest prime minister in more than 200 years. He has risen through the ranks of the Conservative Party in the space of just seven years since he was first elected as an MP in 2015.

"MPs can come into parliament and very quickly gain a name for themselves," Prof Bale says.

"That has destabilised parliamentary politics. It used to be quite hierarchical, but MPs are generally impatient to move up the ladder but also if they think things are not working they would be piling onto Twitter and the rolling news channels to say 'something needs to change - and that includes the leader'."

Some of Britain's former PMs pictured together at the accession of King Charles last month

Prof Bale believes the rise of social and digital media has also made a big difference to how voters view politicians.

In the past, "politicians were not faceless," he says, "but they were not the celebrities they are now. That feeds through to how voters view politics."

Prof Bogdanor disagrees. The governments of David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill during the two world wars, William Gladstone in the 19th century, and more recently Margaret Thatcher could all be described as "presidential," he argues.

"Governments have always been presidential," he says. "The power of the prime minister ebbs and flows really with their electoral position."

Prof Bogdanor believes Mr Sunak might now usher in a period greater stability.

"I cannot see him being overthrown in the next two years. There is going to be economic hardship, but the Conservatives have two years until the next general election."

But Patrick Dunleavy, emeritus professor of political science and public policy at the London School of Economics, believes an election will be held before the two-year deadline.

"I do not think that the two years is a credible timeline now," he says, arguing that pinch points for Mr Sunak include the local council elections next year and then his anniversary in office, depending on his opinion poll ratings.

Prof Dunleavy also sees the problem in other Westminster-style systems. Australia, which is also a parliamentary system, has had nine prime ministers in 12 years, owing in part to what are called spill elections. It has led to Australia being dubbed "coup capital of the democratic world"..

Leadership spills occur when members of the parliamentary party feel that the leader is taking them in the wrong direction, or not delivering on the promises made to those who elected them, and does not have the numbers to back their position.

"The Conservative Party has moved over to full spill election operations. They were threatening Cameron in 2016, they were used against May - she survived the first one then she had to give up - they were used against Boris and then against Truss," Prof Dunleavy says.

"Spill elections are definitely here in the UK."

Watch: Yet another PM, yet another No 10 lectern

- Published5 July 2024

- Published24 October 2022