What's behind the Home Office migrant backlog?

- Published

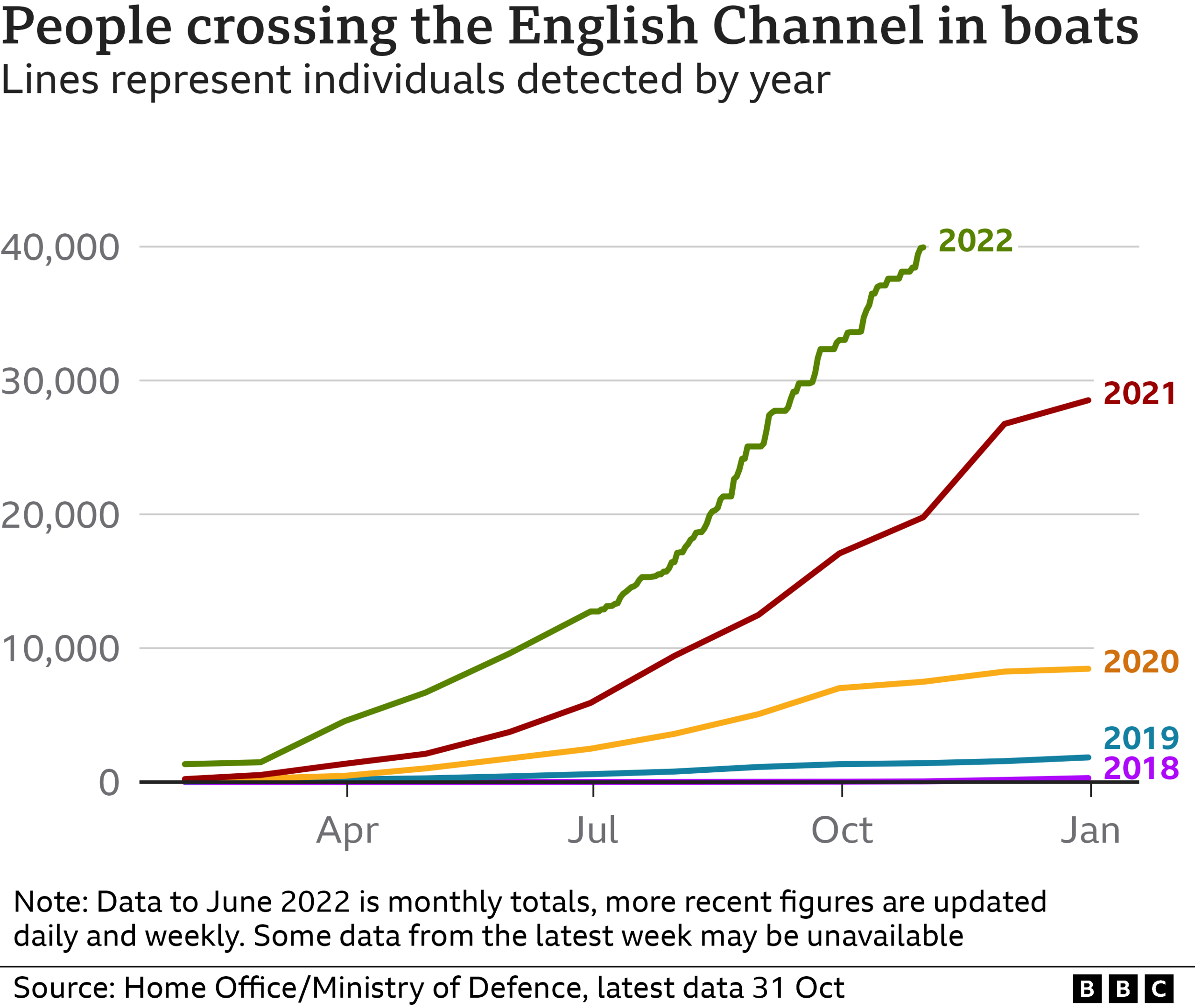

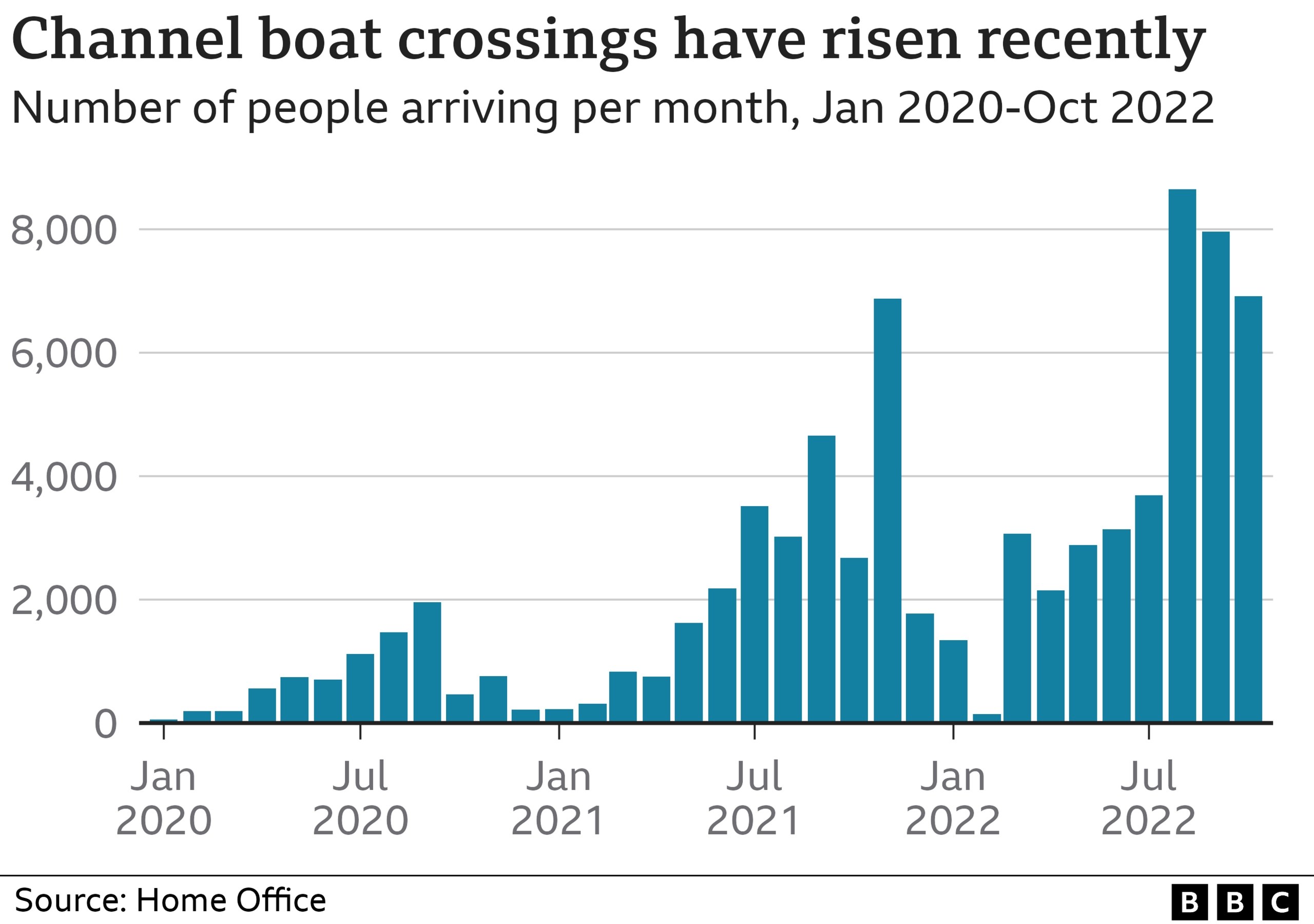

The numbers of people crossing the English Channel are now at unprecedented levels

Four years and four Secretaries of State ago, the Home Office made a pretty small technical change to how its staff should process asylum claims.

Like a Whitehall case study in chaos theory, that policy shift may have triggered a chain of events leading to the government being engulfed in a migration crisis, which critics say it cannot control.

It's now a crisis that has seen an overwhelmed asylum centre branded as wretched by a watchdog. There are community tensions and a counter-terrorism-led investigation into an attack on another migrant facility in Dover. All the while, the numbers of people crossing the English Channel are now at unprecedented levels.

Home Secretary Suella Braverman is under intense political pressure over her handling of the issue, including accusations - claims she denies - that she blocked the use of hotels to ease overcrowding at a migrant processing centre.

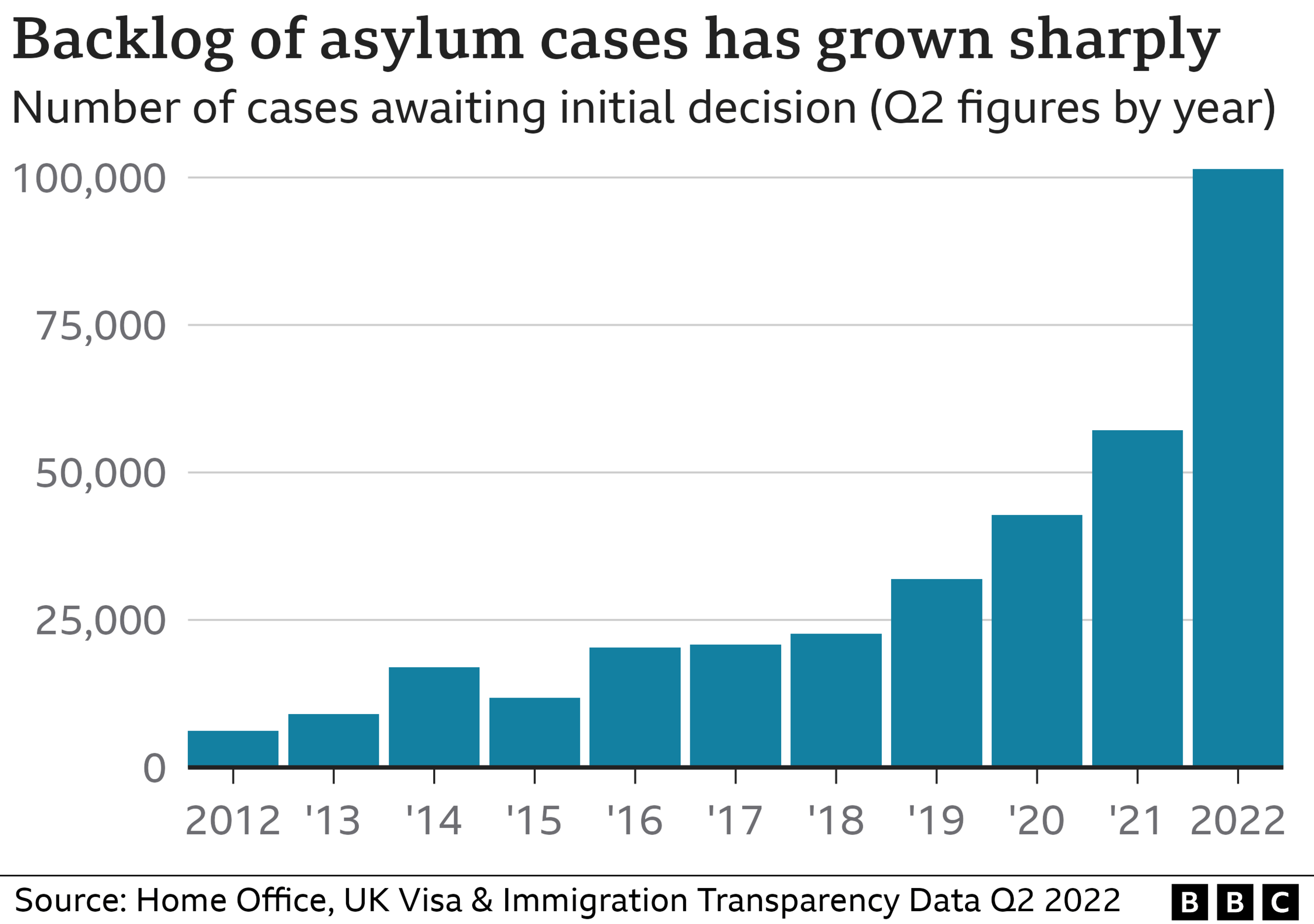

So what evidence is there that the current backlog of asylum seekers is as much about Home Office bureaucracy as it is the number of people arriving?

Graphs showing the year on year numbers crossing the channel

Let's start with a simple guide to how asylum seekers are meant to be managed.

When officials screen a newly-arrived claimant, unless there is good reason to immediately remove them from the UK, their case for protection will need to be considered. That's a lengthy process, which involves looking at their evidence and where they have come from.

If a claimant can't support themselves - which is usually the case - the Home Office then pays for a private landlord to house them.

If the Home Office later decides they have a case to stay, they're then able to work and they will leave the national accommodation system. Those who are rejected are told they must leave - subject to appeals.

As of March this year, there were 85,000 people sitting in Home Office-funded accommodation waiting for a decision on their case - pretty much what the department's experts had said it would be. Of those, around 27,000 were in hotels.

That number has grown because the speed cases have been dealt with has dropped off a cliff.

And that brings us back to that little noticed technical change.

Eight years ago, nine out of 10 asylum claims were being processed within six months. But by late 2018 - four years ago - just a quarter of claims were receiving their initial decision within that target.

In January 2019, the department scrapped the six-month "customer service standard", hoping it would ease pressure on stressed staff, allowing them time to take better decisions on complicated cases.

But instead, the delays got worse.

By June of last year, just 6% of all claims were being dealt with within a six-month window - and MPs learned last week that just 4% of people who arrived in small boats in 2021 have had a decision.

"We struggle to understand why the decision-making process slowed down so dramatically," says Rob McNeill, of Oxford University's Migration Observatory, a specialist research body.

"Why the Home Office chose to [abandon the target] is unclear, but the impact - particularly at a time of increasing arrivals of asylum seekers - has been to create a very large backlog, which has huge impacts all the way through the system - and which is very expensive for the government."

So why does that matter?

Well, quite simply, it has meant that the amount of housing and hotel accommodation available to the Home Office has been filling up because the rate of people going out the other end to a new life has been dropping. And if there is a lack of an exit, then the pressures are going to build and build at the entry point: the Kent coast.

So far this year, there have been almost 40,000 arrivals in Kent. But the number of people waiting for their claim to be processed has climbed higher and faster - leading to today's massive in-tray of 101,000 outstanding cases.

Why is it so bad?

David Neal, the borders watchdog, reported last year that there had been real problems with retention of staff - but officials told MPs last month that a major recruitment boost had been successful - there are 1,000 staff now working on decisions.

He also found that the Home Office's decision-making was incredibly slow. It relied on unmanageable computer systems and massive spreadsheets: it could take each case worker up to 40 minutes just to carry out the simple task of booking an asylum seeker in for an interview.

The mechanisms for dealing with claims of trafficking and modern-day slavery created barriers and simple human errors could grind a case file to a halt.

And while all this was going on - growing backlogs, slowing decisions and housing filling up - the small boats arriving began to rise.

Former Home Secretary Priti Patel made ending English Channel crossings a priority and launched a range of initiatives, including the £120m Rwanda removals plan which is mired in the courts.

But that plan was preceded by one that has had a significant impact on the system - a post-Brexit rule change that has added to the numbers in accommodation.

That new rule declared that people coming from the EU could be blocked from making an asylum claim and sent back to the safe country they had come from.

But there is a problem; the UK has no returns agreement with the EU.

Of the more than 17,000 potential returnees identified under that rule as of last June, only 21 had left our shores. Some have now been allowed to make asylum claims - but it appears more than 9,000 are in a limbo: housed by the Home Office, yet blocked from applying to legally stay and get a job.

And so, when the number of crossings spiked in September, the Home Office had little room to manoeuvre.

Accommodation and hotels around the country were full up - with each additional hotel, according to evidence given to MPs, taking two months to bring into operation.

A spring plan for reception camps on Ministry of Defence bases was scrapped in August amid opposition from both future prime ministers, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak.

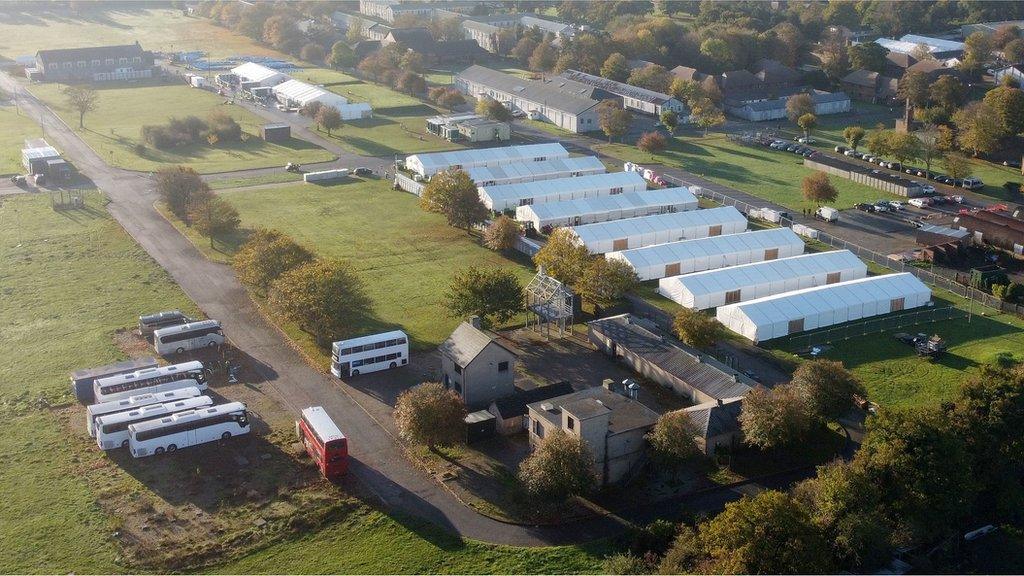

And so the only new facility - the temporary marquees at Manston - largely built as a place to dry out and recover from crossing a dangerous sea - was quickly overwhelmed.

- Published13 December 2023

- Published21 December 2022