Who needs to 'step up' to keep kids safe online?

- Published

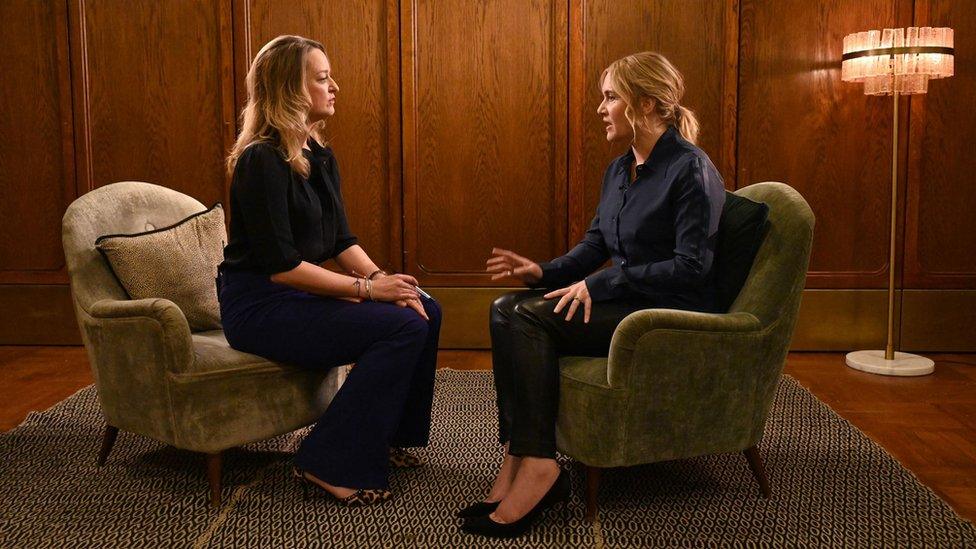

Kate Winslet tells Laura Kuenssberg there should be age blocks for social media sites

"My God, I don't know what I'm supposed to do at all." That's not an admission that you expect to hear from a movie megastar.

But that's how Kate Winslet described some moments of being a mum in the 21st Century, with parents "rendered utterly powerless" as their kids spend more and more time online.

Winslet's new film confronts that dilemma head on. She tells the story of a mother desperately trying to help her daughter, whose mental health has been shattered as she's sucked deeper and deeper into social media.

The drama - I am Ruth - is hard to watch, but hard to look away from. Without giving a terrible spoiler, it does also in the end offer hope.

It's all the more powerful because Winslet's on-screen child is played by her own daughter - Mia Threapleton.

But the Oscar winner hopes the film will prompt a wider conversation about how vulnerable children are.

She suggests some online platforms should be banned for kids and accuses the government and tech firms of "shirking responsibility". You can read the full story here.

"Whoever those people are, they know who they are, they should just step up and do better," she told me.

The UK was going to be the first country in the world to try and solve this problem but there have been so many delays the EU got there first.

The government has again cranked up its plan to regulate what happens online and the Online Safety Bill will be back in the Commons on Monday.

It is a massive piece of law and ministers are worried they might run out of time to get it done.

That said - its coming into force will be a genuine landmark moment.

For years, governments around the world more or less assumed that the exciting tech companies they used to like having photo opportunities with could basically regulate themselves.

That climate soured some time ago. As one senior tech executive described it: "After tech euphoria now the pendulum has swung completely the other way."

And governments, at least in the UK, have concluded platforms that hold so much power cannot be left to supervise themselves.

See Laura Kuenssberg's interview with Kate Winslet in full this Sunday, 4 December

Also on the show is cabinet minister Nadhim Zahawi and Labour's shadow education secretary Bridget Phillipson

On the panel are Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, film-maker Beeban Kidron and Currys plc chief executive Alex Baldock

Watch Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg on BBC One and on BBC iPlayer from 09:00 GMT

Follow live here on the BBC News website from 08:00 and on Twitter @BBCPolitics, external

The communications watchdog Ofcom - which currently looks after TV, radio and phones - will be given the job of setting standards for tech platforms and checking they follow them.

Crucially they'll have the power to impose hefty fines on the companies if they fall short. Alongside that there'll be new criminal offences for things like encouraging self harm.

These are big changes but some of the government's plans to confront the darkest corners of the internet have disappeared.

And to understand what's gone on, we need for a moment to look at what exactly has changed.

Neither ministers nor Ofcom were ever going to instruct Facebook, Instagram, TikTok or any other platform to take down specific content if it didn't break the law.

What they were going to do was define the kind of material that could have caused harm to people.

Companies would then have taken those definitions of racism or misogyny, for example, into account in their own terms and conditions.

The regulator could then hold them to account for if they didn't follow their own rules.

Now that's changed. The government is not going to define what is "legal but harmful" - leaving it up to companies to decide whether to specify those harms in their terms and conditions, if at all.

And if they don't, well, the regulator doesn't have a rule to enforce.

Ministers deny the plan has been watered down but it's hard not to conclude that the tech companies are more able to set the terms as a result of this change.

There'll be a filter for users to get rid of content they don't like - but that puts the responsibility onto the individual rather than the platform.

You may recoil at the idea of the government defining what's right and wrong - or be frustrated that it hasn't gone far enough to tame the tech giants.

What you may well end up though is confused, because this system means different platforms will make different decisions.

And as long as content is not illegal, one former Facebook executive says that for example "if one platform wants to get rid of Tommy Robinson it can, if another platform wants to keep them all on because they are not illegal, they can keep them all on".

The government wants under-18s to be protected from "legal but harmful" online content

But the political truth is that ministers ran into concerns on the Conservative Party's right.

Even with the "legal but harmful" part of the bill scrapped for everyone but under-18s, the legislation overall is still seen by some as a "censors' charter".

And while the idea of giving tech firms the right to scan encrypted messages to track down illegal activity may seem noble, there are genuine fears an important protection of privacy could be fundamentally undermined.

For many people, what happens online is still bewildering. For many parents - Hollywood megastars or not - what happens on teenagers' phones is desperately worrying and these changes can't remove that fear.

The proposed laws won't mean that all harmful material will disappear. And as the former Facebook executive told me: "The big discussion we need to have is at what age should kids go online."

The government has tried to provide at least some solutions to these profound problems.

But as technology advances, the dilemmas may only become more complex over the coming years for parents, the public and the politicians.

I am Ruth can be seen on Thursday 8 December at 21:00 GMT on Channel 4