Laura Kuenssberg: Putin set UK on search for new friends

- Published

If you're reading this in a cold house in the UK with a woolly hat on your head, if you've winced at the cost of filling up the car, if you've taken in Ukrainian refugees, then your life has been changed by Vladimir Putin's decision to wage war against an independent country.

As one diplomat puts it, in 2022 "foreign policy has come home to roost".

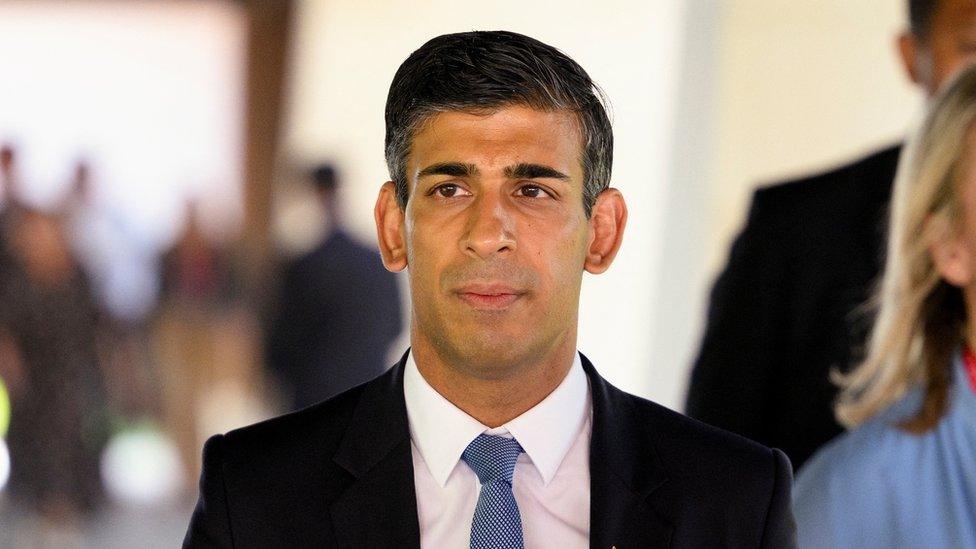

But beyond supporting Ukraine against Russia's aggression, what makes up Rishi Sunak's foreign policy? That's something to ask Foreign Secretary James Cleverly when he is on our show this Sunday.

While Mr Sunak has a ghastly set of problems to attend to at home, part of being an effective prime minister is wielding influence abroad.

But, as one senior former minister laments, there's been little sign of a grand vision, with "demoralisation left, right and centre" instead.

Like any leader, there are some things they have no choice but to do. When it comes to foreign policy, for Mr Sunak, there is the UK's commitment to Ukraine.

Unlike Boris Johnson, he's hardly likely to have Ukrainian streets named after him. But his commitment is as solid as a rock, the right thing to do and politically a no-brainer.

Despite the impact on our fuel bills, there's no sign of the public expecting anything but full-throated support for Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky.

On the programme this week is Foreign Secretary James Cleverly and Labour's shadow health secretary Wes Streeting

Also on the show is Prof Stephen Powis, medical director of NHS England

On the panel is Asda chairman and Conservative peer Stuart Rose, Royal College of Nursing general secretary Pat Cullen and historian Simon Sebag Montefiore

Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg is live on BBC One and iPlayer from 09:00 this Sunday

Follow live text and watch the show here on the BBC News website and on Twitter @BBCPolitics, external

And when it comes to the issue of people arriving in the UK in small boats, efforts are being put into repairing the relationship with France's President Emmanuel Macron.

This was "essentially broken with Boris", according to one Whitehall source, and a better relationship with Paris could bring a resolution to that problem.

There's also been a visible effort by the government to move towards a solution on the Northern Ireland protocol - the trickiest hangover from the Brexit deal minted by Mr Johnson.

Long gone is the tough talk and sabre rattling, with one EU ambassador saying Mr Sunak's government has "completely changed the mood".

The determination is to play nice, for now, but resolving the long-standing dispute over implementing extra rules for Northern Ireland, which kept closer ties with the EU than the rest of the UK, needs more than a friendly conversation, it needs one or both sides to budge.

One former diplomat warns there will be a "showdown moment" ahead of next year's 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement which brought peace to Northern Ireland.

Mr Sunak faces the same dilemma as the other post-Brexit prime ministers. He could compromise and get an agreement but risk a giant row with his party - or refuse to budge and trigger a massive fight with our biggest trading partner.

Watch: Rishi Sunak meets President Zelensky in Kyiv for the first time as prime minister

The tone of government policy is different, but as one ambassador tells me: "The big question is do we see any willingness to make a deal?"

There's been unavoidable pressure too on the prime minister to turn up the heat on China - not least because of the noisy demands from his backbenches - as President Xi Jinping's increasingly hard-line tactics have become more obvious.

Mr Sunak stepped along a careful line in his white tie and tails speech at the Lord Mayor's banquet. "Not as soft and squishy" as David Cameron was on China, one former diplomat said, "but not quite as hawkish as Liz Truss".

Governments can't ignore China if they want to solve issues like climate change, but they cannot also cut themselves off from an evolving mega power.

It is hard so far to see how Mr Sunak's government will manage these unavoidable problems differently.

Yet this week we may see the foreign secretary fill in some of the blanks in Mr Sunak's foreign policy.

On Monday, Mr Cleverly will make his pitch to focus on new friends - "future partnerships" around the world - essentially building better relationships with countries who are neither the global bad guys nor Britain's traditional allies.

Mr Cleverly will argue for closer ties with countries like Indonesia, South Africa and Brazil whose influence is growing.

The idea is to lengthen the UK's list of global friends - it's described as the "really smart and obvious thing to do".

But one senior Conservative MP worries the government's foreign policy will be "devoid of any meaningful depth but heavy on flirtation with cameras", adding that it's time to spell out its objectives and "show some grit when it comes to threats from autocratic states".

Mr Sunak said foreign policy would go through an "evolutionary leap". But when you look down the list of challenges it's hard to see, so far, anything that matches that grand language.

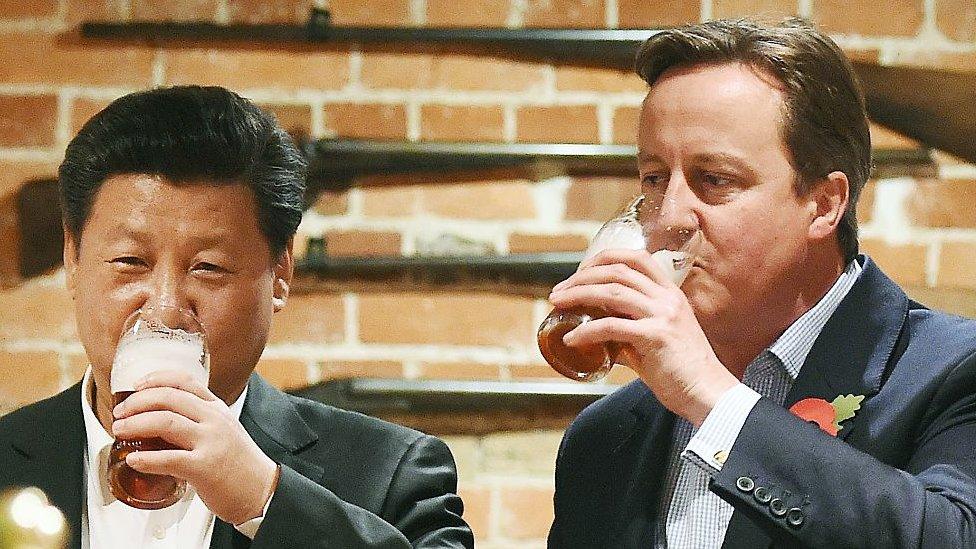

Don't expect Mr Sunak's China policy to include a pint with President Xi Jinping

It's not Theresa May's "Global Britain", David Cameron's "golden era" with China or Tony Blair's "ethical foreign policy" - much maligned though they all came to be.

And on the world stage, as one former senior official says, Mr Sunak "is the junior guy at the table" and world leaders are not sure after years of the Tories knocking lumps out of each other whether he has control or they should be working out what Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer would do instead.

Mr Sunak is a pragmatist prime minister - not a foreign philosopher. His backers would argue that's exactly what's required right now.

But he is boxed in by an unhappy party which disagrees with itself on policy towards China or the EU.

And his detractors claim his political personality is dwarfed by the scale of the challenge.

"The more he talks, the less he says," a Labour source tells me.

"Both at home and abroad he is in danger of being the Incredible Shrinking Prime Minister - the man who got smaller in office."

The world stage can provide huge opportunities for prime ministers, but Mr Sunak's chance of turning things round for his struggling party starts with confronting problems at home.

- Published29 November 2022

- Published19 November 2022

- Published16 November 2022

- Published15 November 2022