County lines: How a child’s phones helped smash a trafficking gang

- Published

Six gang members have been jailed for trafficking a teenage drug runner. Rather than prosecute the boy, detectives pursued the adults controlling him.

This is the story of the mobile phones that unlocked the case.

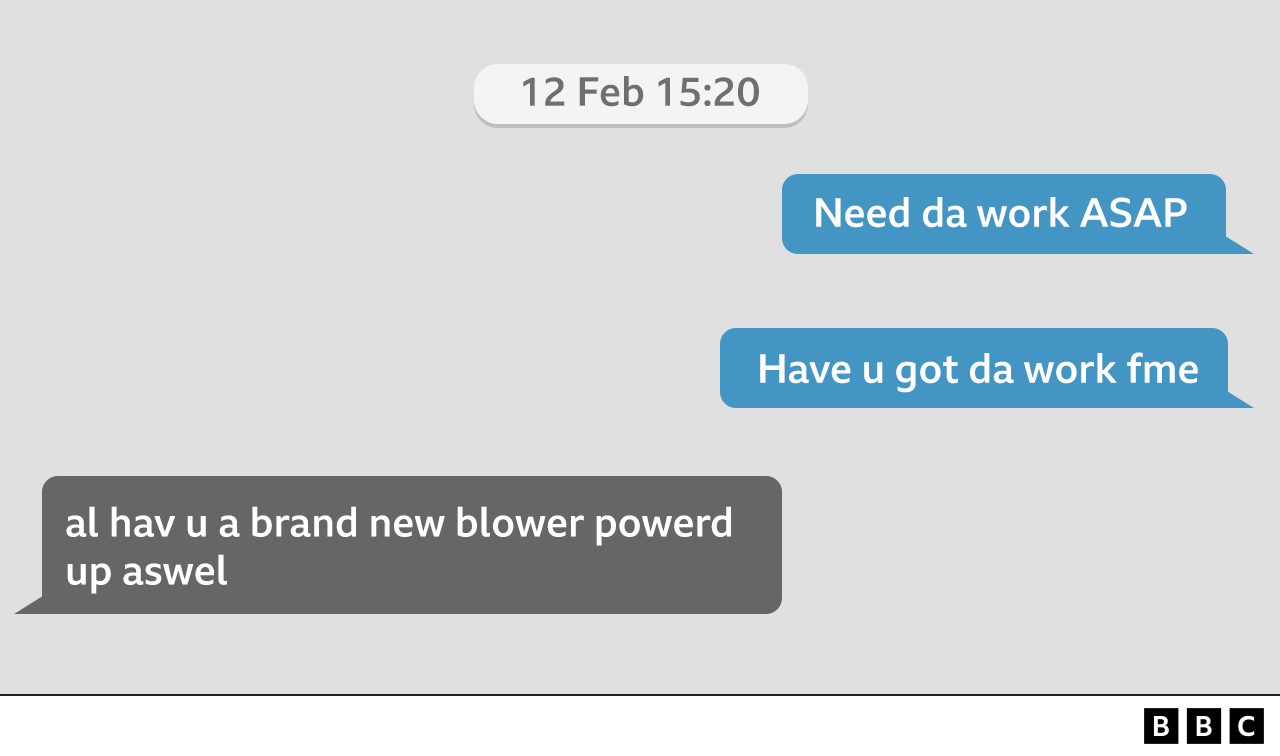

It is February 2021, and a teenage boy sends text messages to a contact he called "Main Man" asking about a job. He receives a reply almost instantly, telling him there is work - and it comes with a new phone.

It may appear to be a fairly harmless exchange - except that the job is drug dealing, and the employer Wesley Hankin, a man in his late 20s, is hundreds of miles away from the 14-year-old, in a prison cell in Dorset.

For the next two weeks, the boy would travel around the country at the beck and call of a drug-dealing gang, who used a phone number known as the "TJ Line" to contact customers.

His first trip, arranged by Hankin, was to Liverpool to pick up the brand new phone. The Nokia 105 was an early indication that the gangster life may not be as glamorous as the teenager expected.

No apps, no fancy operating system, just cheap with lots of battery life and good for texting and storing contacts.

But it would be enough to help pave the way for the largest prosecution of a county lines gang for child trafficking under the Modern Slavery Act.

Just a fortnight after starting work for the gang, the boy was arrested in north Wales for selling £20 worth of heroin and cocaine to an undercover police officer. On him, he had hundreds of wraps of heroin and crack cocaine valued at nearly £2,500.

Officers were already on to the dealers, but to put together a case that proved the gang had been trafficking, they would need to understand the boy's movements. Who was he in contact with? Who was ferrying him around and putting him up?

It would be a complicated case. Throughout, the teenager refused to answer officers' questions. So they turned to his seized phones to piece together events.

The devices were a window into the bleak world of a child drug dealer - controlled and exploited by adult criminals.

Phone data revealed large numbers of taxi bookings as the boy moved around Wigan dealing - while the notes section of the Nokia recorded his takings, his debts and how many drugs he still had to sell.

In the past, the teenager - who we can't name for legal reasons - would have been prosecuted for drugs offences and no doubt have been quickly replaced by another willing foot soldier for the gang.

But police and prosecutors opted for the more difficult, and perhaps more controversial, route to treat him as a victim and to go after those who had been controlling him.

"This was a young boy who had been trafficked across the north west," says Det Supt Simon Williams of North Wales Police.

"He was probably at more risk than he understood himself. So, in my eyes, certainly a victim not a perpetrator."

Det Supt Simon Williams said he views the use of young drug runners as "child abuse"

In cases like this involving young people, police and prosecutors are encouraged to try to understand the child's own account of events. This is known as the "voice of the child".

But as the boy wouldn't cooperate, says DSI Williams, the phones would serve as the child's voice.

"Once we got early indications of the sorts of things that we were seeing on the phone, and the level of exploitation, it became obvious that we were dealing with a vulnerable young child," he says.

Officers discovered that in February 2021 the boy - who was living in care - had posted on a social media site his availability to be a drug dealer.

He was then contacted by a man telling him to use the phone app Snapchat, where messages are automatically deleted once read.

Soon afterwards, Wesley Hankin got in touch. A career criminal, he was serving time in HMP Prison Portland on the south coast after having been convicted of conspiring to supply heroin and cocaine, and wounding. He was texting from a mobile smuggled into his cell.

Hankin was not charged with trafficking, as police found no evidence he knew he was directing a child

That same day, the teenager ran away from home and ended up in Wigan. There, he spent a week in different addresses - so-called trap houses - properties used for stashing and dealing drugs.

Videos on his own phone appear to show him glorifying the lifestyle in which he had found himself. In one, he waves a long knife with a serrated edge and a baton. In another, he is handling £10 and £20 notes - the proceeds of his dealing. He zooms in to dozens of wraps of heroin and cocaine.

The boy recorded video on his own phone

When he ran out of drugs, evidence from the Nokia shows he was sent back to Liverpool to pick up more, directed again by Hankin from his prison cell. By now, the inmate was using a second illicit mobile. The first had been found on the floor of his cell after the prison authorities had detected a phone signal.

Vicky Bannister was jailed for 18 months for her role in trafficking the boy

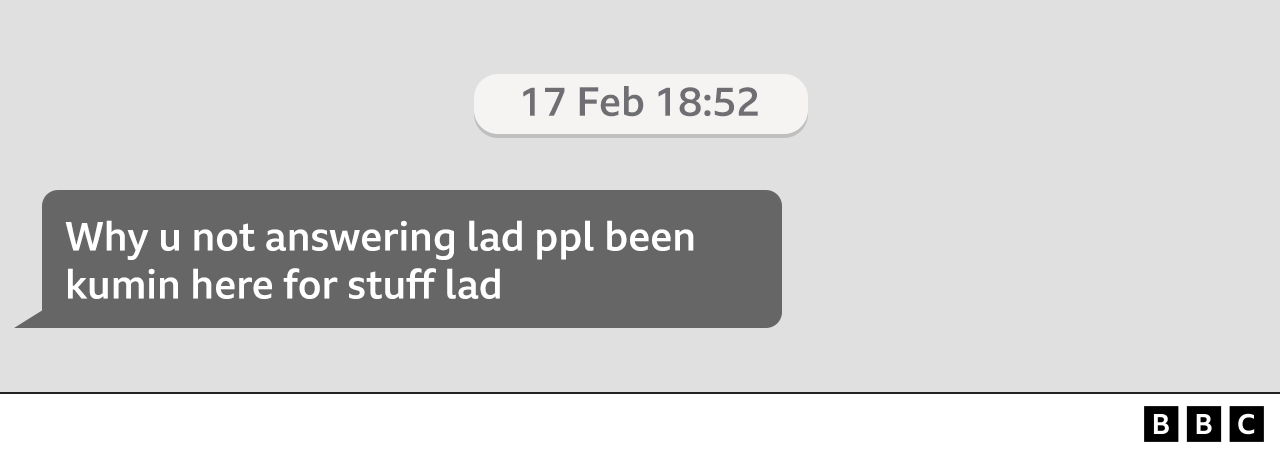

Other evidence from the boy's Nokia shows how one of the gang, Vicky Bannister - who lived at one of the Wigan trap houses - sent him texts. The 34-year-old repeatedly referred to her young charge as "lad" in the messages - and in one, she complained that he wasn't around for customers.

Once the teenager finished his dealing in Wigan, he was moved again. In a 10-day period, he was driven to Liverpool, then to Bedford and back to Liverpool, before being deployed to north Wales.

He ended up in the resort town of Rhyl, which has been repeatedly targeted by out-of-town drug gangs preying on vulnerable people.

The boy was again being directed by adults working the TJ Line.

But police were on to them and had already made several arrests.

Police arresting a gang member - Gareth Mark Jones

Officers were monitoring the activities of the phone line, and an undercover officer posed as a customer.

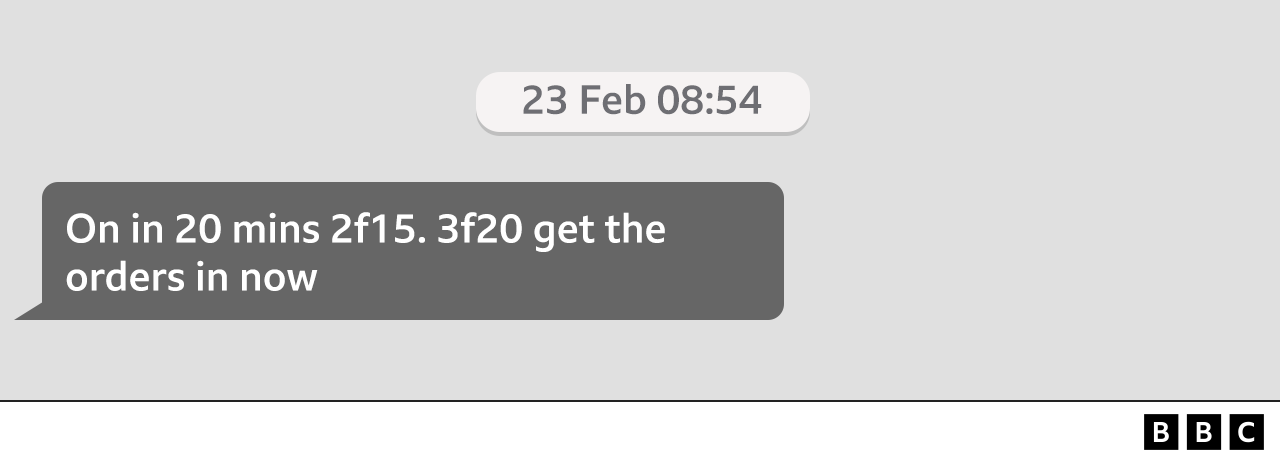

Gang member Michael Hill, one of the boy's handlers, sent the officer and hundreds of other customers a text advertising the price and availability of Class A drugs.

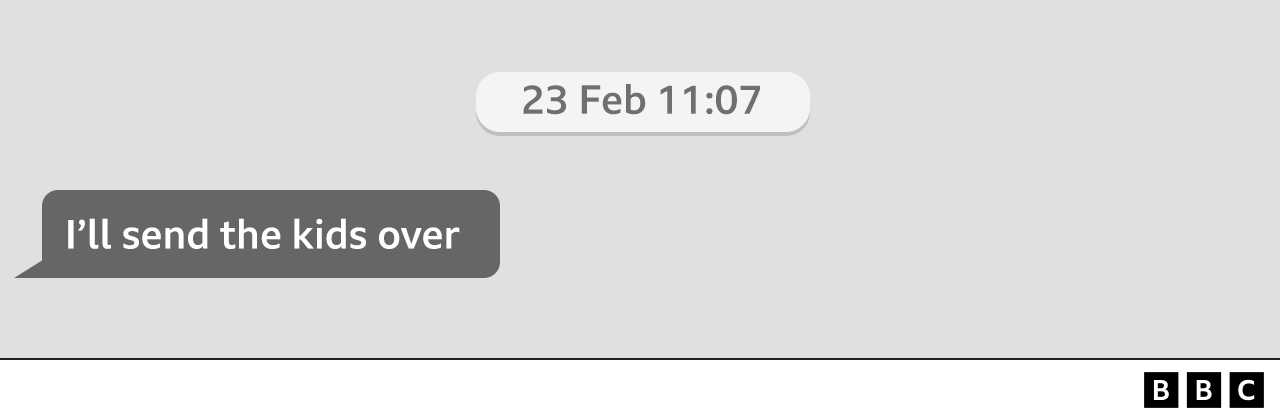

When the officer rang Hill with her order, he replied:

The transaction was carried out in a hut on the promenade in Rhyl by the boy and another teenager.

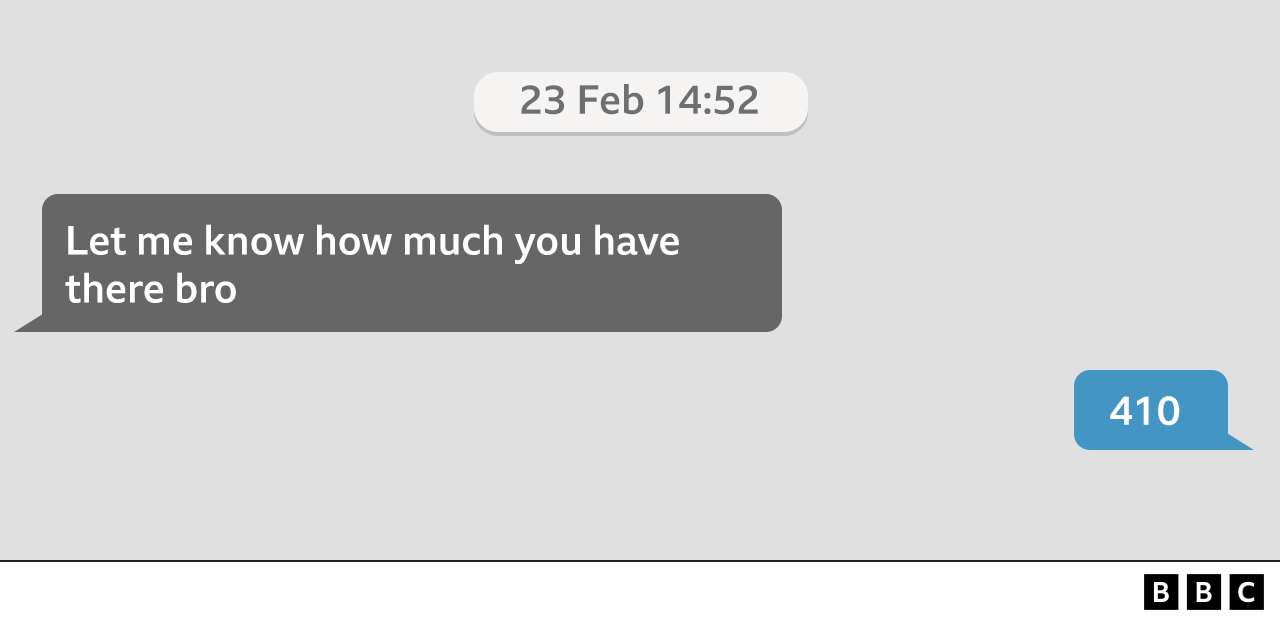

Later that day, the boy's minder Hill enquired about the day's takings:

Two days later, the boy was sent to the Cob nature reserve on the edge of Rhyl. After selling more drugs to the undercover police officer, he was arrested.

'We see it as child abuse'

Even though the boy had been eager to get involved and was arrested with Class A drugs, the police defend their decision to treat him as a victim.

"It was more important that we safeguarded him as a victim, and went after those that were profiting from that criminality," says DSI Williams. "We see it as child abuse."

As the evidence mounted, seven gang members admitted their guilt - including Michael Hill who pleaded guilty to conspiracy to traffic, and supplying cocaine and heroin. Hill was jailed for seven years and two months at Caernarfon Crown Court on Friday.

The prisoner, Wesley Hankin, admitted the drugs offences but was not charged with trafficking because there was no evidence he knew he was directing a child. Judge Nicola Saffman told him: "You let him run up a debt in your organisation" and sent "menacing" text messages.

In one, Hankin falsely accused the boy of "working with the feds" (police) which, said the judge, "would have been terrifying for him".

Hankin was jailed for 10 years and two months. He was also served with a 15-year slavery and trafficking risk order which is a criminal offence if breached, and places limits on him.

Three others, including trap house owner Vicky Bannister, were convicted at the trial - which senior police officers hope will lead to more prosecutions for modern slavery. Bannister was jailed for 18 months.

The focus should be on "those who are causing the most harm to our communities," says DCI Lindsey Billany from the National County Lines Coordination Centre, which gathers together experts from across law enforcement.

She acknowledges that police forces don't always take a consistent approach. Some still prefer the easier task of pressing drug charges instead of trafficking.

The latter "does take a bit longer" says DCI Billany but "we have to take that time to understand who the perpetrators are and who are the victims, otherwise we'll continue seeing more victims."

When the boy was arrested, police alerted the Home Office through the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) that he was a potential victim of modern slavery. He was one of 1,729 children that year who were flagged as suspected of being exploited by county lines gangs.

Although he avoided prosecution, DSI Williams says "he will need ongoing safeguarding. I wouldn't sit here and say that he's completely sorted now in terms of his vulnerabilities."

What about his long-term prospects?

"I'd like to think that deep down he is supportive of the action we've taken," he says. He adds that he hopes the boy will eventually be "able to put this type of activity behind him and lead a safe, normal life".