Chronic backlog of serious-crime cases hits courts

- Published

Leicester Crown Court: Created courtroom "99" - on paper - to manage its backlog

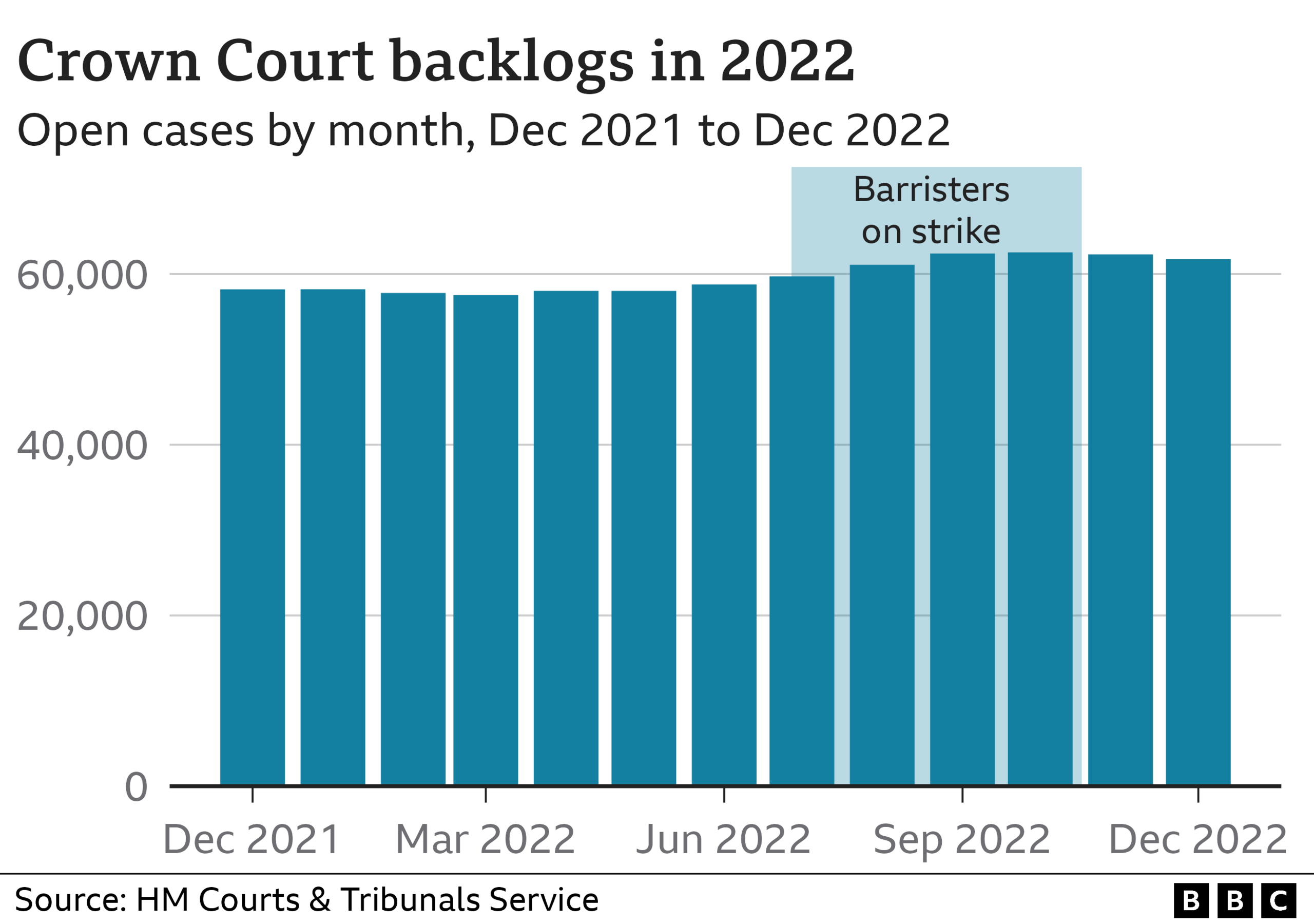

The Crown Courts in England and Wales ended 2022 with chronic and near-record backlogs, despite more than a year of attempts to speed up justice.

There were 61,737 outstanding serious-crime cases - the highest year-end figure so far, although down from a peak in the autumn.

Some centres even created a fictional courtroom to better manage their cases.

The government has a target of cutting the backlog to 53,000 - essentially, the pre-pandemic level - by March 2025.

But the challenges involved loom large for ministers, policymakers and the judiciary.

Social distancing

The backlog began to grow in 2019, when the government capped the number of days judges could sit to hear cases - partly because of predictions about falling crime rates but also to save money. Courtrooms were locked up, despite work that needed doing.

Courts then closed during lockdown - and even after they reopened, individual courtrooms too small to safely implement social distancing stayed shut.

By December 2020, the Crown Court backlog hit a record of more than 57,000 cases. By December 2021, it had grown to 58,204. And that year, the average time taken to deal with cases hit a record 708 days.

Since the pandemic, the Ministry of Justice has funded "Nightingale courts" - temporary additional rooms around the country, often in conference centres or hotels. And last week, officials told MPs in the Justice Committee in Parliament the system was operating at capacity.

But the latest figures suggest there may be a bigger problem - a lack of available lawyers and judges.

Ministers have blamed last year's strike over pay by defence barristers, which added to the pile of unresolved prosecutions.

But the profession says too many lawyers have drifted away from criminal work, because they can earn a better living elsewhere, leaving, the Criminal Bar Association says, a shortage of defence counsel - and prosecutors.

Last year's strike by barristers in England and Wales added to backlogs but was not the sole factor

In the first nine months of last year, 235 Crown Court trials were put off on the day they were due to start, because there was no prosecutor available. In 2019, just 19 cases were adjourned for the same reason.

The government has just agreed to up prosecutors' pay - to match the deal that led defence barristers to suspend their strike. But what about judges?

In the year to September 2022, 127 trials were put off, again on the day, because there was no judge available.

And even though the Ministry of Justice says there is no longer a cap on sitting days for judges, there is real concern at the Royal Courts of Justice.

The last recruitment round for new Crown Court judges fell short by 16 appointments - a "significant shortfall", Lord Chief Justice Lord Burnett says, representing 3,200 days of court time every year.

His team have been:

trying to persuade more senior lawyers to sit as part-time judges

bringing more recently retired judges back

allowing experienced district judges from magistrates' courts to deal with more serious crimes

But they cannot control the rate of cases coming into court - and that could be about to soar.

The Home Office could soon hit a target to recruit 20,000 additional police officers, returning the workforce to near its 2010 level. And that should lead to more criminals being charged and prosecuted. That may then collide with a lack of time, space, judges and lawyers in court. So how can the courts manage?

As new defendants come into the system, they cannot be left in limbo. They have a right to know when their case will be heard and there are legal limits on how long someone can be left in a cell when they have not been convicted of a crime.

So to help manage the cases that can't be immediately dealt with, some courts have been quite literally imaginative.

They've created courtrooms that do not actually exist, so the staff can administratively allocate a defendant a date in the system - and reschedule their case to another day, if it cannot be fit in to a real courtroom.

Leicester Crown Court's "Court 99" is one example. It exists only on paper to help staff temporarily manage the cases they cannot progress before a judge on a particular day.

On Thursday, 9 February, 31 cases were on Court 99's public list - with notes next to them indicating they would in all likelihood all be put off for another day because of lack of time.

The government is convinced its target of cutting the backlog to 53,000 by March 2025 is achievable. MPs have asked for milestones along the way - but the Ministry of Justice has not provided any.

A spokesman for the MoJ said: "The number of outstanding cases in the Crown Court is continuing to fall, dropping by almost 800 cases in two months now that courts are able to run at full capacity.

"We are doing all we can to ensure this number continues to fall. Measures such as lifting the cap on the number of days courts can sit, and recruiting more judges are helping restore the swift access to justice that victims deserve."

What counts as swift, however, is a matter of debate. There is a long road ahead - and for many victims and defendants, there will still be a long wait for justice.