Terri White: How I fear for the 'ghost children' missing from school

- Published

More than 140,000 schoolchildren in England were officially "severely absent" in the summer term of 2022, according to official Department of Education figures - and the number of these pupils, missing at least 50% of classes, is growing.

They are away from school for a variety of reasons - including anxiety and mental health, special educational needs and disabilities. But, like me when I was growing up, some of the children are likely to be extremely vulnerable.

Many of them stopped attending school during the pandemic - to never return. And now, they are not really on anyone's radar.

I know how important school becomes when home isn't safe, because I was that vulnerable kid. My childhood was something to survive, with abuse the consistent feature of my early years.

I grew up in a Derbyshire village called Inkersall, and I still remember how it felt to walk through the doors of my small primary school each morning.

My body would unfurl - shoulders loosening, chin emerging, fists opening.

From 08:45 to 15:25, I could press pause on the violence and chaos at home. A weight would lift and - while it was temporary, lasting only until the bell rang - I gobbled up those seven hours of relief.

Back at home, I worried and panicked constantly. I wet the bed, wet my pants.

What did the tone and tenor of his voice mean for me? What did it mean for my mum? Could we protect our dog - Sweep - from his boots? Would I vomit?

And here's what happens when you don't have to worry about these things - when you're fed, looked after, and encouraged - you simply get to learn.

Terri White: Finding Britain's Ghost Children - from BBC Radio 5 Live

School saved journalist Terri White - she wants to know why so many children are missing from the classroom.

What would have happened to me if I'd been stopped from going to school? If I had risked being around too much, triggering a temper. That the men who hurt us and threatened to do us serious harm - my mum's partners - could have done something way worse.

As I moved into adulthood, I was able to build a different life for myself.

I went to university. I became a journalist. I eventually ended up editing magazines. But without school, absolutely none of this would've been possible.

Education gave me everything I now have.

I thought about this a lot when schools closed indefinitely as part of the first Covid-19 lockdown.

Vulnerable children could still attend school, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in March 2020, but I immediately feared that many wouldn't, and that some would be withheld from school.

Now, there are 134% more "ghost children" than before the pandemic, according to analysis of the government figures by the centre-right think tank, the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ). The number of severely absent children in autumn 2019 - the last full term before lockdown - was 60,244. The latest figure, from summer 2022, was 140,843.

I needed to investigate what was happening to kids today and why school wasn't the salvation for some of them, like it had been for me.

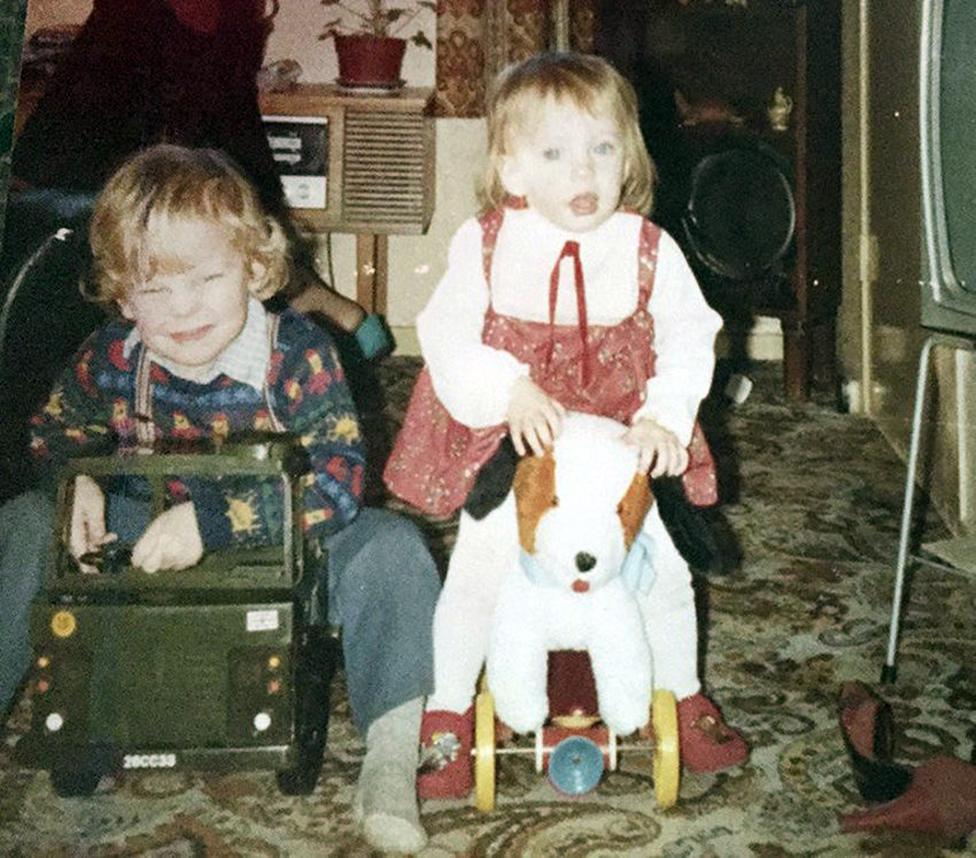

Family photo of young Terri on a toy dog

In the Radio 5 Live and BBC Sounds podcast series, Terri White: Finding Britain's Ghost Children, I travel across the country to find out where these kids are, why they're absent and what is being done to address the issue.

I also went back to my hometown, hoping that a journey into my past may shed some light on what kids face in the present.

Unlike some kids, the classroom wasn't a place I was desperate to escape every day. Instead, the piles of books, stacks of paper and pots of pens were my escape. They were a portal to another world. Another life.

I have long wondered what would have happened to me if I hadn't had school.

The worst-case scenario was something I'd considered - especially when it came to the years spent under the same roof as the most violent man. The one we escaped by fleeing to a refuge for six weeks.

That worst-case scenario came true for a child during that first lockdown - Arthur Labinjo-Hughes. The six-year-old from Solihull who loved school but was kept at home when classroom doors started to reopen across England in June 2020. Arthur's father, Thomas Hughes, gave teachers a series of excuses for the boy's absence.

Arthur Labinjo-Hughes died in June 2020

What the father didn't want the school to know was that his son was being tortured and abused - and had been for months. Nine days after the boy should have returned to classes, Arthur died. He had been assaulted by his father's partner, Emma Tustin.

School made me believe that not only was I protected within its grounds - but also that I was worth something, I could be something, I could be someone.

I was lucky. I was supported by wonderful teachers - none more so than Mrs Webley, my teacher in junior school.

I was in her class when me and my mum ran to the refuge. And it was Mrs Webley who called in social services one day when something was clearly awry at home.

I'd always known that she'd had a hugely positive part to play in my life as a schoolkid, but when I reunited with her on my trip home, I realised quite how protected I had felt in her classroom.

Before my visit, she'd sent me a letter.

Terri was reunited with her junior school teacher Mrs Webley

"You seemed to know that the only way out of poverty for a woman was education," she wrote.

And somehow, I did.

I think that knowledge could only have come from her. The knowledge that life could not just be different, but safer. And that her classroom, if I worked hard, was the portal to that place.

It's knowledge - rather than just a gut instinct - that tells those of us born into disadvantaged circumstances that we have a mountain to climb to get anywhere close to parity of opportunity.

Today, disadvantaged kids are significantly over-represented in school absence figures. The CSJ analysis reveals that children who receive free school meals or have special educational needs are three times more likely to be "ghost children" - while those with an education, health and care plan are five times more likely.

The Children's Commissioner for England, Dame Rachel de Souza, speaking at the Education Select Committee hearing into absence in schools on 7 March, rightly called school absence "one of the issues of our age".

But there is hope. There can be change.

I saw it for myself when I travelled to Barrow in Cumbria to meet Caroline Walker, headteacher of Parkside Academy, a school in a deprived area that had long struggled with absence.

Ms Walker told me she had spent the morning rounding up the kids who'd not turned up for school. Literally climbing through a window to rouse the parent of one absent boy - before getting the child to school, and his dad smartened and sobered up.

The headteacher runs breakfast clubs so kids can eat, helps parents with employment, and works to understand every family dynamic playing out in her school.

She's part teacher, part social worker, part superhero.

But we need more than remarkable individuals going above and beyond.

A family photo of Terri as a little girl

The recently abandoned School's Bill for England presented a great opportunity - particularly around the creation of a national register that would help track all children, including those not on a school roll.

Dame Rachel De Souza has also called for real-time data, so that problems with absence can be recognised and dealt with immediately - as opposed to the current situation where there's a significant lag with figures.

But these are first steps. Once we know where all of our children are, those who aren't receiving a proper education at home and should be in school need to be helped to re-join the education system.

In the absence of the Bill, backbench MPs are now looking at how they can progress certain individual elements, including - according to a CSJ source - legislation for a Children Not in School Register.

The vast majority of children are in school and learning, says a Department for Education spokesperson.

"We work closely with schools, trusts, governing bodies, and local authorities to identify pupils who are at risk of becoming, or who are persistently absent… working together to support those children to return to regular and consistent education."

The spokesperson did not specifically address severely absent children - those missing at least 50% of school.

There really is no more time to waste. As each year passes, that's another year of education a vulnerable child is losing - that thousands of children are losing.

And perhaps most crucially, children whose lives could be saved by the simple act of walking through those gates and going to school every day.

Shoulders loosening, chin emerging, fists opening.

- Published7 December 2022