Sudan: How do countries evacuate people from a war zone?

- Published

More than 1,000 EU citizens have now been evacuated - with German soldiers pictured here in Jordan, before their military evacuation operation

The British government has evacuated diplomats and their families from Sudan, in a swift operation that saw staff and their families flown out of the country on Sunday.

It comes after a military power struggle erupted in the country last week between two opposing forces, causing deadly shooting and shelling in capital city Khartoum. Hundreds of people have been killed, including five aid workers.

Thousands of British citizens remain in Sudan, with many saying they feel abandoned by the UK government following the evacuation. Other countries including France and Germany have begun evacuating their nationals. The government says it is still in touch with stuck Britons and is "looking at every single possible option" for extracting them.

In a fraught and rapidly changing environment, how does a government bring its diplomats to safety, especially if they are being targeted?

BBC News asked Philip Ingram, who served in the British army for more than 26 years and has worked as a military planner and intelligence officer.

Stage one: Planning and preparation

Military personnel constantly rehearse and fine-tune these types of operations, says Mr Ingram, with Ministry of Defence and Foreign Office staff also regularly visiting British embassies around the world to discuss their evacuation plans.

The risks of using military personnel to extract people from war zones "cannot be understated", Mr Ingram says, explaining that an evacuation operation is a "last resort".

An operation like this one should not be conducted without consulting other allied countries that may also be looking to evacuate their staff from the place, he adds.

The US and UK announced on Sunday they had flown diplomats out of the country, while France, Germany, Italy and Spain have also been evacuating diplomats and citizens.

Countries will often work together in what's known as a non-combatant evacuation operation (NEO) co-ordination group to execute an evacuation together.

If one country extracts its staff without consulting international partners, it can put other diplomats at greater risk of being targeted, he explains.

A sudden evacuation by one country can cause a "domino effect", he says, meaning that warring factions could see those who remain as targets or "potential hostages".

Stage two: The element of surprise

Once an evacuation is planned, military liaison staff arrive at the embassy very quickly, says Mr Ingram. This can include military leaders, special forces and personnel from the Chief of Joint Operations planning team, based in the British Armed Forces' Northwood Headquarters in Hertfordshire and whose job is to plan and execute overseas operations.

Meanwhile, evacuation plans will be kept under wraps to avoid any of the warring sides taking hostages or shooting the escaping convoy in order to blame this attack on an opposing faction.

"When ministers are asked exactly what's going on, they turn around [and] they don't brief the detail," Mr Ingram explains.

"One of the critical pieces of this is surprise: to get in and get out quickly before any of the warring factions can react properly. So that's why we heard nothing."

Stage three: Getting in

The personnel, aircraft and logistics needed for this kind of operation would have been "forward based", says Mr Ingram, meaning that they would have been put in place nearer Sudan in advance.

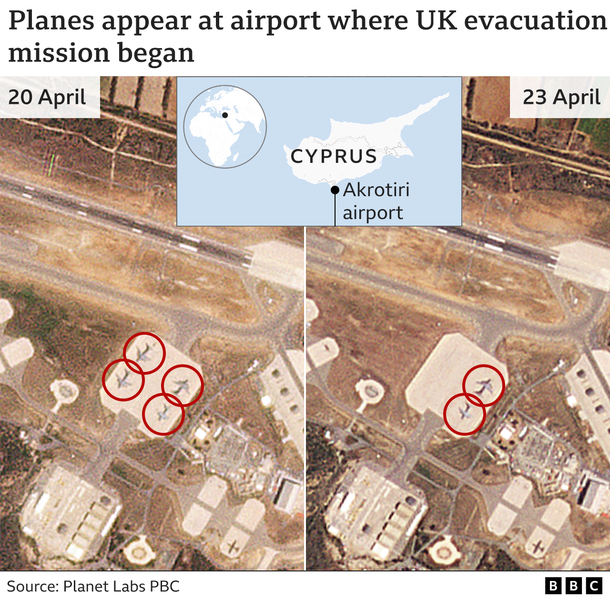

In this case, he says, they were stationed at RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus, which is a permanent UK military base in close flying distance of Sudan. Based here were a number of transport aircraft, he explains, including Airbus A400Ms and at least one Lockheed C-130J Hercules.

A satellite image taken at the airbase shows two planes which appear to match A400Ms disappearing from view on Sunday.

Images of the airfield show four planes on 20 April, with only two remaining there on 23 April. On all other visible images of the airfield in April there are no planes in this area.

Foreign Office Minister Andrew Mitchell told the Commons on Monday that the "highly complex" operation had involved more than 1,200 British military personnel.

When the evacuation began, Mr Ingram says it is likely that French, British and US forces worked together to get to Khartoum, with American troops using Chinook helicopters.

"They will have [then] met up with the representatives, the planning and liaison individuals that will have been in the embassies who will source vehicles and other bits and pieces for them from within embassy resources," he says.

Stage four: Getting out

When military forces arrived, evacuees would have been called into the embassy or another central location, Mr Ingram explains.

Once all gathered together, they would be put into vehicles and taken to the "extraction point" in secret, he continues. In this case, he says this was "executed almost perfectly".

The BBC understands that UK diplomats and their families were flown in military aircraft from Wadi Seidna air base in Sudan - in an SAS-led evacuation mission on Sunday.

Satellite images from the airport north of Khartoum show a plane on the runway which appears to match one of the planes used in the mission - an A400M military aircraft.

The above image was taken of the airport at 11:35 GMT, shortly before the evacuation flight is thought to have left Wadi Seidna around midday on Sunday.

The grey aircraft pictured appeared on the airstrip on Sunday, and wasn't there in the days prior to the mission. Aviation experts we spoke to confirmed that its wing style and dimensions were consistent with the A400M.

Ministers have emphasised how dangerous these evacuation operations are. Mr Mitchell said when the French military was evacuating its diplomats, they were "shot at as they came out through the embassy gateway" and that one of their special forces personnel was now "gravely ill".

The UK's Armed Forces Minister James Heappey praised the British mission, saying "it went without a hitch, which we're very pleased with."

French soldiers evacuate French citizens as part of their operation on Sunday

But he added: "Of course the job isn't done".

"Work is under way and has been all weekend, and all the back end of last week, to give the prime minister and Cobra options for what else could be done to support the wider community of British nationals in Sudan."

Additional reporting by Jake Horton, Erwen Rivault and Tom Spencer

- Published24 April 2023