Windrush: Hundreds with chronic and mental illness sent back to Caribbean

- Published

Hundreds of long-term sick and mentally ill people from the Windrush generation were sent back to the Caribbean in what has been described as a "historic injustice", the BBC has found.

Formerly classified documents reveal at least 411 people were sent back between the 1950s and the early 1970s, under a scheme that was meant to be voluntary.

Families say they were ripped apart and some were never reunited.

The UK government said it was committed to tackling the injustices of the era.

A spokesman said: "We recognise the campaigning of families seeking to address the historic injustice faced by their loved ones, and remain absolutely committed to righting the wrongs faced by those in the Windrush generation."

The revelations - which echo the Windrush scandal, in which hundreds of Commonwealth citizens, many from the Caribbean, were wrongly deported - have sparked calls for a public inquiry into the repatriation policy.

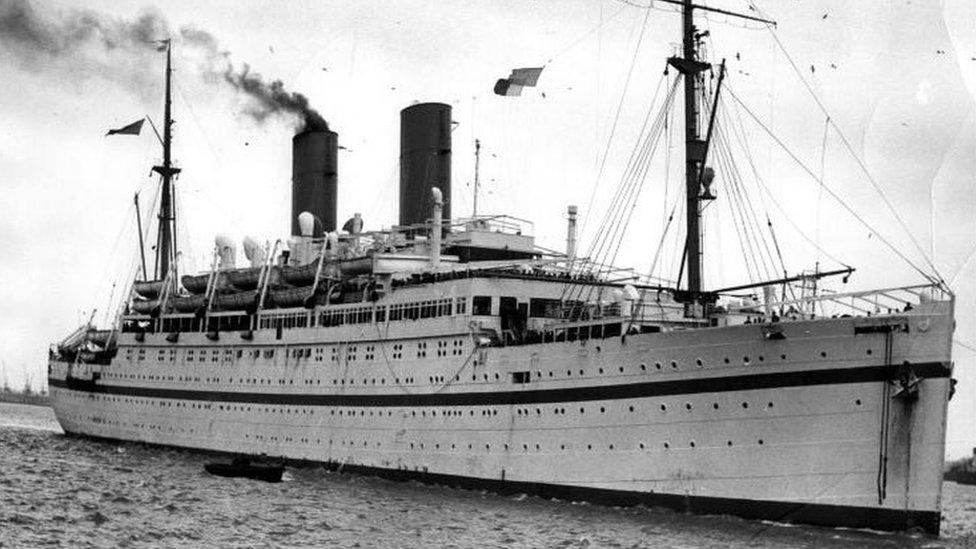

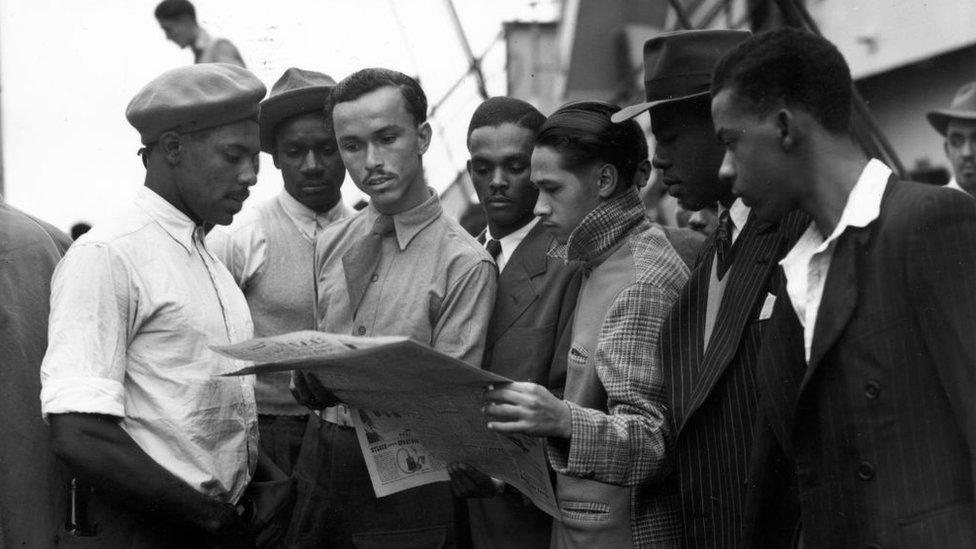

Those sent back were among thousands who moved from British colonies to the UK in the decades after World War Two. They were known as the Windrush generation, named after one of the first ships to arrive in the UK, the HMT Empire Windrush. This year will mark the 75th anniversary of the first arrivals.

BBC News has now unearthed documents in the National Archives revealing the scale of the policy. Some experts now think the scheme may have been unlawful because not all the patients had the mental capacity to agree to leave.

June Armatrading's father, Joseph, was one of those sent back.

Like other people from the Caribbean who travelled to the UK after the war, Joseph was British. His birthplace - St Kitts - was a British colony and still administered directly from London, and he was a British passport holder.

Joseph arrived in the UK in 1954 and lived in Nottingham with his wife and five daughters. However, he began struggling with his mental health in the 1960s and was diagnosed with paranoid psychosis. In 1966, he was returned to St Kitts. He never saw his family again.

June, who is now 65, said her mother told her and her sisters their father had "abandoned" them.

June Armatrading was told her father had left his family - but now believes he was "abandoned" by the state

She grew up always believing her father didn't love them, causing her a "massive, big heartbreak".

Yet the BBC has seen a letter, written by Joseph, asking to return to the UK so he could rejoin his family. Little is known about what happened to Joseph after this.

And in previously confidential letters, government officials admitted the procedure of repatriating Mr Armatrading had "not been correct". He had been wrongly stripped of his passport, the papers revealed.

When we showed the letters to Ms Armatrading, she was shocked.

"I'm upset. It's upsetting, it's really upsetting… how dare they?" she said. "This was a vulnerable man. You're supposed to look after your vulnerable people, and they didn't. They just left him - they abandoned him."

Marcia Fenton was taken into care as a toddler.

Her mother, Sylvia Calvert, had been sectioned and sent back to Jamaica in the late 1960s, and her father couldn't cope on his own.

Marcia Fenton says she was "robbed" when her mother, Sylvia, was sectioned and sent to Jamaica

Mother and daughter were only reunited many years later in Jamaica. Sylvia had been discharged by this point, but was still unwell. She died in 2007.

Marcia still wants to find out what happened to her mother when she arrived back in Jamaica. All she knows is she spent some time in Bellevue Hospital, in the island's capital, Kingston.

"Her being sent back to Jamaica robbed me of a mother," Marcia told the BBC.

She wants an inquiry into how and why people like her mother were sent back. "No-one should have been repatriated who was mentally ill," she said. "The British government should apologise."

How did the policy work?

BBC analysis of documents in the National Archives shows that 411 chronically sick and mentally ill patients were sent back to Commonwealth nations in the Caribbean, between 1958 and 1970.

However, government departments do not appear to have kept comprehensive records, so the number could be higher.

The National Assistance Board - the forerunner of the Department for Work and Pensions - was usually in charge of the process.

Government letters and policy documents from the archives indicate that each patient should have "expressed a wish to return". They suggest repatriation should only be carried out if it would "benefit" patients and there were "suitable arrangements" for when they returned.

However, it is questionable whether vulnerable patients could make these decisions and whether such suitable arrangements existed. One academic paper said mental health care in the Caribbean at that time lacked "trained personnel and resources".

British government officials were concerned not to give the impression they were "actively trying to offload… those Commonwealth citizens for whom Britain had little use".

The Windrush generation is named after one of the first ships to arrive in the UK, the HMT Empire Windrush

This does not seem to have convinced officials in Jamaica. In 1963, the Office of the High Commissioner wrote to the British government complaining that UK hospitals were requesting repatriations "largely on the grounds of pressure on beds, or other hospital services".

The Windrush generation, as "Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies" (CUKCs), enjoyed the same legal status as anyone born in the UK.

However, Prof James Hampshire of the University of Sussex said that from the first arrival of Commonwealth people from the Caribbean, there was a desire on the part of both Labour and Conservative governments to restrict their numbers.

"The intent and effect of legislation that was passed in that period [1960s and 70s] was to restrict some kinds of migration and not other kinds. It was primarily aimed at what was referred to at the time as 'coloured immigration'."

Prof Kris Gledhill, who has formerly sat as a tribunal judge on mental health cases, said it was questionable whether the practice of repatriating mentally ill patients was legal.

He said: "What you're doing is you're relying on a 'voluntary choice' which, were you to properly assess the capacity of the person to make that choice, you'd say they don't have capacity."

Immigration lawyer Jacqueline McKenzie, of Leigh Day, represented hundreds of victims of the 2018 Windrush scandal. About the repatriation of the sick and mentally ill, she said: "It's absolutely shocking that this was happening.

"Lives have been destroyed. The state now owes it to the descendants of people to provide them with answers and some sort of redress."

Strong regrets

Doctors who researched the impact of being sent back to the Caribbean found it had a negative impact and that many wanted to return to the UK.

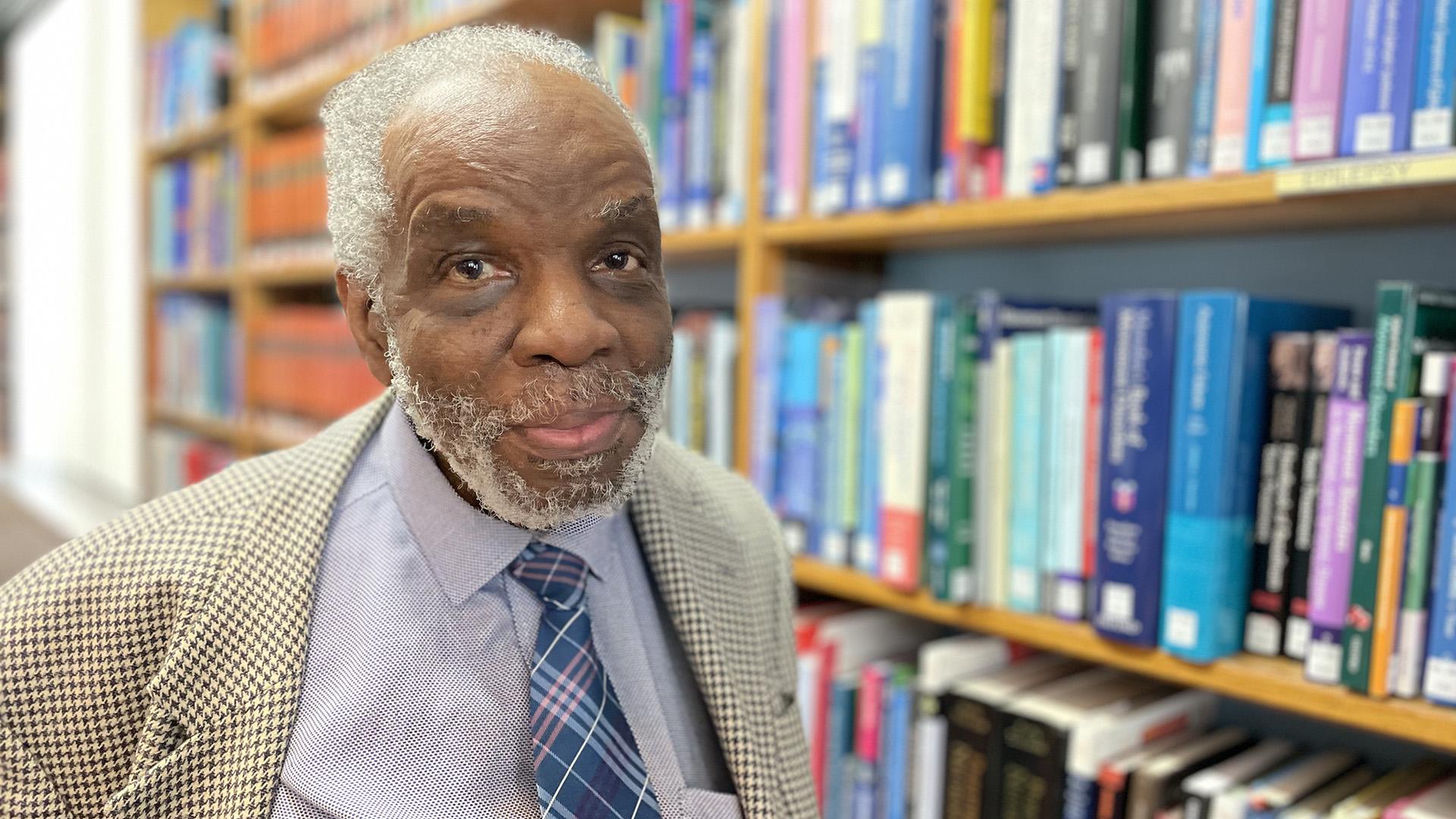

In the early 1970s, Dr Aggrey Burke - the UK's first black NHS consultant psychiatrist - concluded it had not been in the best interests of patients with severe mental illness to send them from the UK to Jamaica's Bellevue Hospital.

He now says there was a lack of curiosity about what happened to the patients: "No one seemed to have an interest in 'what then?' The next stage."

Dr Aggrey Burke concluded that it was not in the best interests of patients to have been sent back to Jamaica

Another psychiatrist in the 1970s, Dr George Mahy in Barbados, reviewed the cases of about 200 patients with psychiatric illnesses originally from the Caribbean.

He found that nearly 52% had been advised to return from the UK and in many cases they were given financial aid from the UK government. He said that many of these patients had strong regrets and wanted to return to England.

Responding to the BBC, a government spokesperson said: "The wellbeing of patients in hospital detained under the Mental Health Act is paramount. The law has changed since the time of these cases - now an independent tribunal has to agree that any repatriation would be in the best interests of the patient."

No photos survive of Joseph Armatrading. At her home in Nottingham, his daughter June says she remembers seeing one of him with her and her sisters, but at some point over the years it was mislaid.

However, she is determined that her father's story is not forgotten.

"The government still needs to answer these questions as to what happened to my dad, what happened to Joseph Armatrading? They've left us lost."

If you feel this may have happened to someone you know you can share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

- Published26 January 2023

- Published24 November 2021