The 'gay tax' facing same-sex couples starting a family

- Published

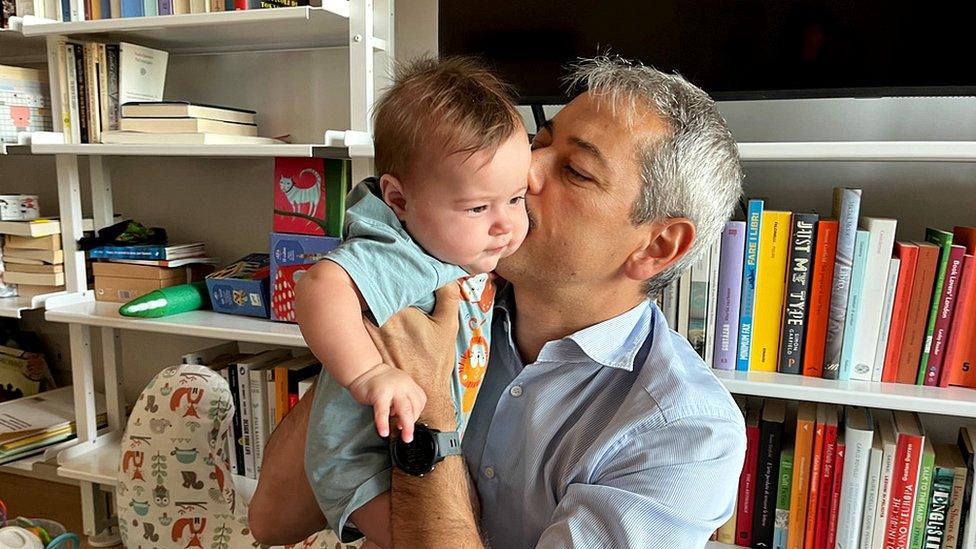

Kate and Keri Davies welcomed Luca after moving abroad, where they could save for IVF

Same-sex couples are still having to pay thousands of pounds before they can access NHS fertility treatment, BBC News has found.

In England, the NHS will fund in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) for heterosexual couples who have been trying for a baby unsuccessfully for at least two years and meet certain other criteria such as age and weight.

But same-sex couples are often expected to demonstrate their infertility before the NHS will fund IVF - and to do so must pay privately for between three and 12 rounds of artificial insemination.

Couples say they have spent more than £20,000 on the treatment.

Last year, the government promised fairer access to NHS fertility treatment for same-sex couples and single women, saying they would no longer need to privately fund rounds of artificial insemination before becoming eligible.

But after BBC News contacted all 42 Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) in England - which make the final decision about who can have NHS-funded IVF in their local area - its analysis found:

Only four offer fertility treatment to same-sex couples who have not already paid privately for artificial insemination

A further 10 are currently reviewing their policies

For those couples, same-sex and heterosexual, who qualify for IVF, the number of attempts they can access varies by location - some ICBs offer up to three cycles, others only one

Campaigners have called the need to privately fund rounds of artificial insemination a "gay tax" and urged the government to follow through on its promise to "remove financial barriers".

The Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) says there is a 10-year plan to improve how the health system listens to women and girls.

But while campaigners and policymakers wrangle over the details, there is a real-life impact for couples dreaming of starting a family.

In-vitro fertilisation (IVF) - the process during which an egg is removed from a woman's ovaries and fertilised with sperm in a laboratory. The fertilised egg, called an embryo, is then returned to the woman's womb to grow and develop

Intrauterine insemination (IUI) - a fertility treatment that involves directly inserting sperm into a woman's womb

Shauna Mansbridge, 30, has always wanted to have a baby. But when she and her partner, Faye Hawkins, went to see their GP, in Dorset, they were told they would only qualify for IVF on the NHS if they had already self-funded 12 unsuccessful cycles of artificial insemination.

The cost varies but Shauna and Faye, 33, discovered it would cost them at least £30,000 for 12 rounds of intrauterine insemination (IUI).

"It's the one time in my life I've felt discriminated against," Faye says, "and I didn't think it would be by the NHS."

Shauna and Faye have spent their life savings and still have not had a baby

Although a cycle of artificial insemination is cheaper than a cycle of IVF, the chances of success are lower and it can involve paying for tests, medication and sperm.

And most sperm banks will ship to registered fertility clinics only, leaving most same-sex couples with no choice but to have treatment there.

Given the cost of IUI, and the likely emotional toll of repeated attempts, Shauna and Faye decided their money would be better spent paying privately for IVF instead of trying to meet the criteria for NHS-funded treatment.

And the couple have now spent their life savings - £22,000, what might have been a deposit on a house or paid for a wedding - in pursuit of their dream of starting a family.

"We had to make a lot of sacrifices," Shauna says, "but this is our only route to motherhood."

They have undergone two IVF cycles and the process is taking its toll on them.

"There's all these stages [of treatment] - and you get to one stage and you're disappointed, you get to another stage, you're a little bit more disappointed, and you just don't have control over the outcomes," Shauna says. "It's tough on both of us."

Contacted about Faye and Shauna's case, NHS Dorset told BBC News it would consider couples who had had six rounds of IUI. But BBC News has seen a letter from the NHS that incorrectly states Faye and Shauna would need 12.

Scotland is the only place in the UK that provides donor insemination to same-sex couples without requiring them to have private treatments first.

Northern Ireland and Wales have similar requirements to England - and access varies by locality.

Surrogacy, which is one of the ways same-sex couples can have children, is not available on the NHS.

No way we could make it work in UK

Kate Davies gave birth to Luca earlier this year, after she and her wife, Keri, spent more than £17,000 on artificial insemination and IVF.

The couple, both teachers, moved to China and worked there for a couple of years to save more money for their future.

Kate says current policies are pricing lesbians out of having children.

Kate and Keri Davies moved abroad, where they were able to save for IVF

"There's no way we would have been able to make it work in the UK," she says. "We've got friends who are having to get loans to try and start a family. And then if that's not successful, you're left with a big loan and no baby. It's a vicious cycle and it's devastating."

They would have expected to pay something towards treatment, they say, but the existing rules are like a "gay tax".

Kerri says: "We've chosen to start a family - but we didn't choose to be gay."

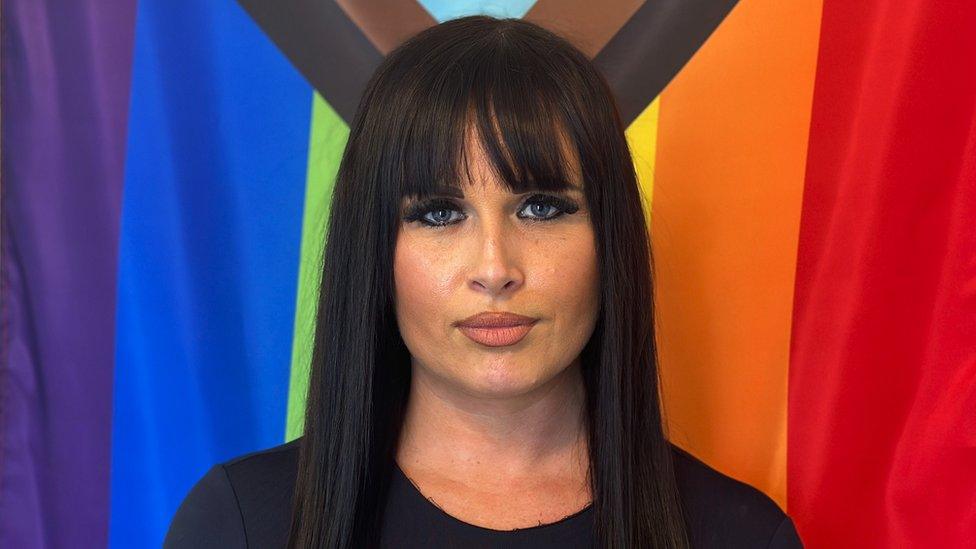

Laura-Rose Thorogood founded LGBT Mummies after she and her wife discovered how complicated it was to find out what fertility support was available and how much it cost.

She says existing policies are leading some LGBT people to put themselves at risk obtaining sperm from a "known donor", someone they are friends with or related to - or have met online.

"Home insemination has really worked for some people - and they have a great relationship with their donor, which is wonderful, but for others it can be dangerous," Laura-Rose says. "Some who don't get access to fertility funding are going down alternative routes where they're having some donors online saying, 'We'll donate to you if you do it in the natural way, if you have intercourse with me.'"

LGBT Mummies founder Laura-Rose Thorogood warns some people feel forced down dangerous routes to become parents

As well as health risks, external, if people do not use registered banks or clinics to obtain sperm, there is also the possibility a donor could later try to claim parental rights over a child.

Laura-Rose says she receives hundreds of enquiries from people who are "despairing" and do not have 10 years to wait for the rules to change.

"Having a family and a child, we feel, is a human right," she says. "And that human right has been taken away from people in our community,"

The Department of Health says it expects the variations in NHS-funded fertility services to start improving this year.

"Our Women's Health Strategy for England sets out our 10-year ambitions for boosting health and wellbeing and improving how the health and care system listens to women and girls," it said.

An NHS official said: "While these decisions are legally for local health commissioners, it is absolutely right that they provide equal access to services according to the needs of people within their areas - and the NHS nationally is supporting them to do this."

- Published22 July 2023

- Published23 September 2023

- Published15 September 2023

- Published29 September 2023