National Archives: Thatcher was desperate to stop Spycatcher publication

- Published

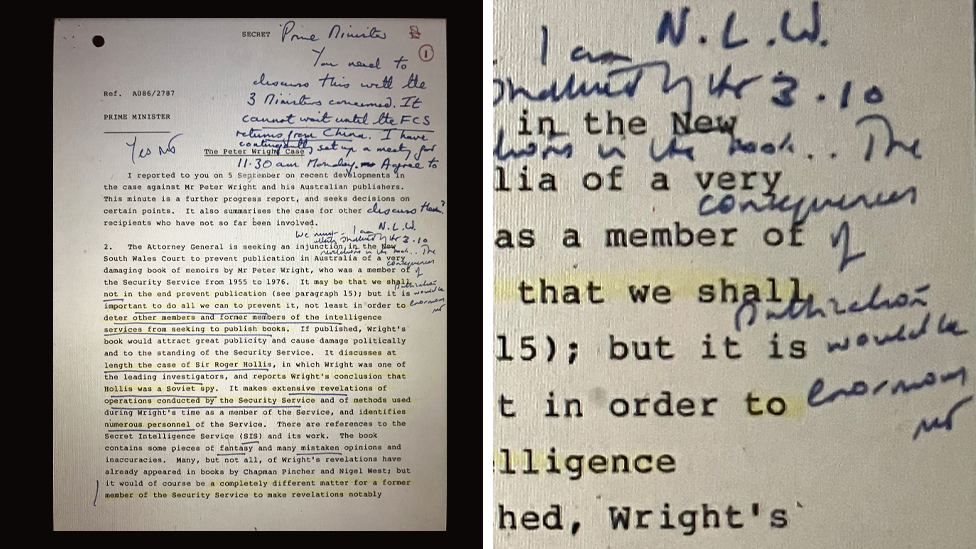

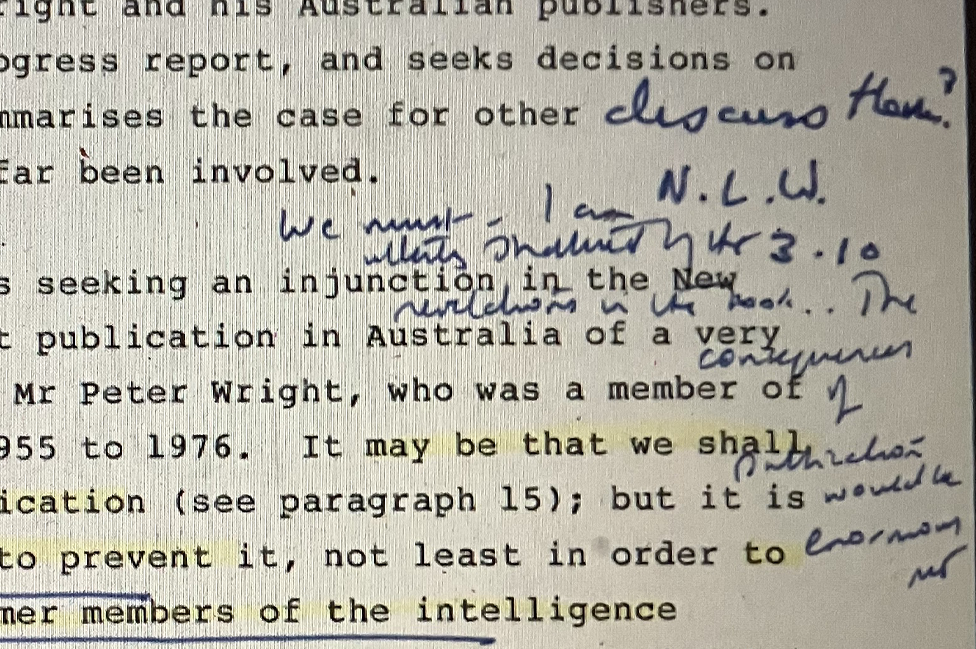

The handwritten note by Mrs Thatcher annotating a briefing document about Peter Wright's memoir

A former spy's memoir in the 1980s left then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher "shattered", according to newly released files.

Spycatcher, by ex-MI5 officer Peter Wright, made explosive claims about UK espionage operations. The government tried to stop its publication.

The files show the extent of the panic over the memoir's threatened release.

"The consequences of publication would be enormous," Thatcher scribbled on a briefing note by her cabinet secretary.

The former prime minister's files on international bestseller Spycatcher have been hotly awaited - they were due to be released 10 years ago, but were judged too sensitive by the National Archives, in Kew, south-west London, at the time. Some papers have been retained.

Peter Wright served for 21 years in MI5 before leaving in 1976. His memoir Spycatcher, the unpublished manuscript of which Mrs Thatcher read in 1986, detailed operations, alleged a former MI5 director general had been a Soviet spy, and claimed MI5 officers had plotted in the mid-1970s against the then-Prime Minister Harold Wilson. All these claims were dismissed by the government.

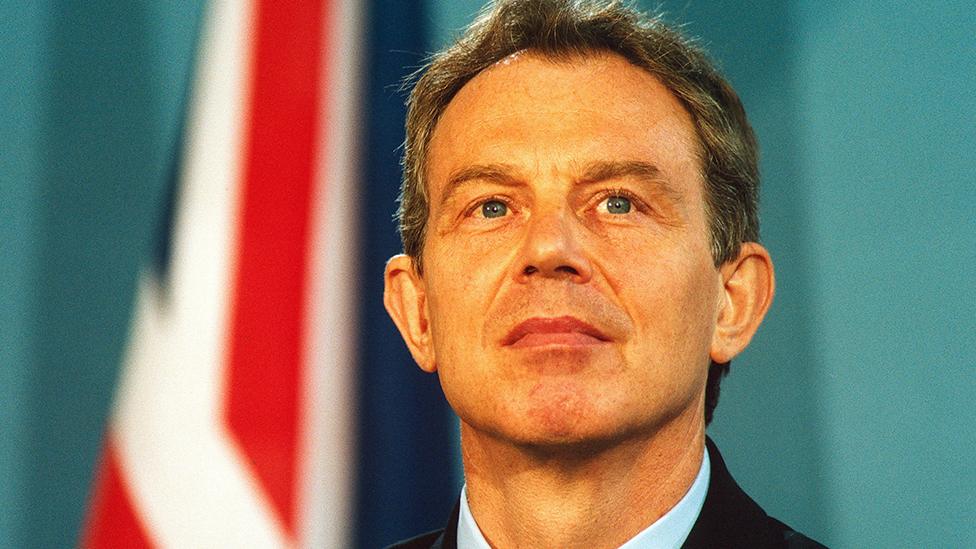

Peter Wright in Sydney, 1988

The most explosive claims had already been revealed in Their Trade is Treachery, by Harry Chapman Pincher, published five years earlier, with Peter Wright as its main - anonymous - source.

But it was the notion that an MI5 officer could publish a detailed memoir under his own name which alarmed the prime minister. Mrs Thatcher and her advisors believed this would set a dangerous precedent.

"The consequences would be enormous" writes Margaret Thatcher

Government ministers managed to block its publication in the UK but failed to stop its subsequent publication in Australia, despite a high profile and - for the UK - embarrassing court case.

The publicity, and the book, fuelled speculation about MI5's activities and the actions of its personnel.

The newly released National Archive files show this led to the public acknowledgment of the Security Service for the first time.

MI5 had become a "constant target for public comment and scrutiny", wrote then-Home Secretary Douglas Hurd to Mrs Thatcher on 30 March 1988.

It had made it difficult for MI5 to do its work, he said.

"The publicity has started to make it harder for the Service to get co-operation from people on whom they rely for information and help," he wrote. Operations were affected and valuable information lost.

He added that the director general of MI5 feared the "public criticism could eventually reduce the willingness of our Allies to share their secrets".

Mr Hurd said the director general supported legislation that would place MI5 on a statutory basis for the first time and it would "form part of an effective response to Wright".

The prime minister initially appeared reluctant.

"The case for legislation prevails," he wrote. The prime minister responded: "If it can be limited."

Discussion of the new bill took place amongst a tiny group with all correspondence marked Top Secret.

Meanwhile, Peter Wright's revelations continued to have an impact. He had spoken to the journalist David Leigh, who had written a book called The Wilson Plot which alleged that MI5 officers in the 1970s had conspired to undermine Harold Wilson.

Mr Wilson wrote to Mrs Thatcher on 21 July 1988. "I am very troubled indeed," he said. "I do not know what, if anything, can be done." He hoped that the government might try to block publication, as it had with Spycatcher.

But the government lost in October 1988 and both books were published internationally.

The very next month the government introduced the Security Service Act to "bolster public confidence and support" in the service, according to a note sent to Conservative MPs.

"The Spycatcher scandal contributed more than anything to bring the spies out of the cold," according to the specialist historian Calder Walton.

"It laid bare how incompatible it was to have intelligence services operating in a secret constitutional never-never land and allowed them to become publicly accountable."

After the Security Services Act, the government publicly acknowledged the Secret Intelligence Service [SIS] - commonly known as MI6 - and UK intelligence agency GCHQ. Later, the Intelligence and Security Committee was set up in Parliament to have statutory oversight of UK intelligence.

Today, MI5 has its own Instagram account and its boss gives interviews to the media.

Related topics

- Published29 December 2023