What can be done about Post Office scandal convictions?

- Published

Sub-postmasters and mistresses celebrated the quashing of their convictions

It's the biggest miscarriage of justice ever - and the government is under pressure to end it.

Hundreds of sub-postmasters were wrongly convicted and have been waiting years to clear their name.

There's also the question of compensation. Many sub-postmasters paid out thousands of pounds of their own money for shortfalls that were caused by the faulty Horizon software.

Justice Secretary Alex Chalk says he wants a speedy solution to the Post Office scandal, but each solution has drawbacks - and it may take longer to solve than people would like.

Option one: A one-off law exonerating all

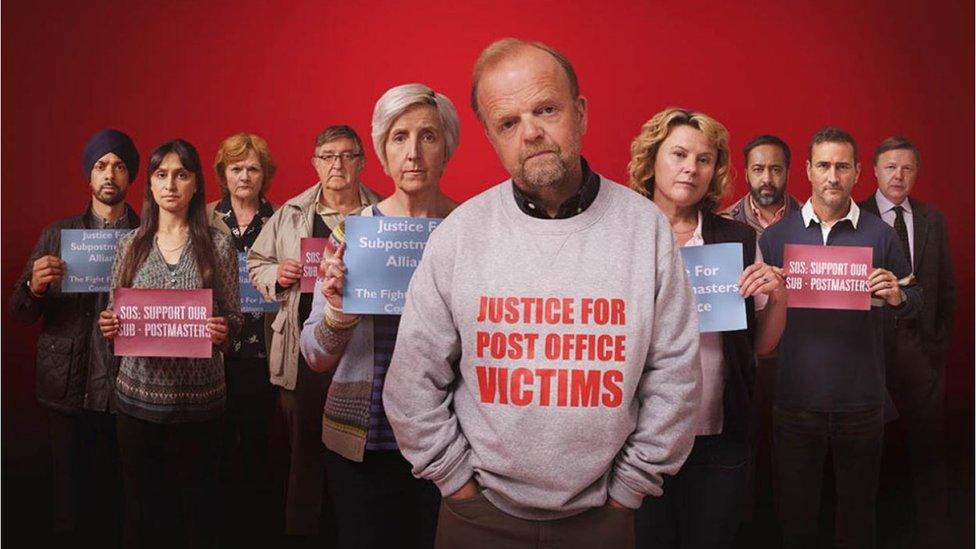

Mr Bates vs the Post Office told the story of the Post Office's Horizon IT scandal

The courts and the decisions of judges are constitutionally independent of politicians and Parliament.

That "separation of powers" makes this option difficult to do - but we know that Alex Chalk is considering whether a bill could be made to work without compromising the sensitive constitutional balance.

In a letter to the Times on Tuesday, Sir Robert Buckland, one of Mr Chalk's predecessors, argued that the convictions are so exceptional they require "an exceptional solution".

All of the miscarriages relate to the same simple allegation that the Post Office hid the truth about the Horizon system's flaws - and therefore a one-off Act of Parliament to quash all of the convictions could be justified.

More on the Post Office scandal

What's wrong with that?

It's got cross-party support but ministers have a legal duty to protect the independence of judges from political meddling.

Any bill quashing convictions, no matter how noble its aims, could fall foul of that duty. And it risks paving the way for future politicians to do it again - and perhaps next time for their pals.

"If you use Parliament in this way, it is in a sense a parliamentary interference in the judicial process of our country," says Dominic Grieve KC, the former Attorney General.

"It could be done. But it's a shortcut."

Lord Thomas, the former Lord Chief Justice, told the BBC that there would be another problem with one-size-fits-all legislation.

"One of the difficulties with pursuing the course suggested of legislation is... there must be a real chance you would be freeing people who had committed a crime [unrelated to the Horizon system]," he said. "If you are to set up a system by legislation [to quash convictions], it's unprecedented."

Option two: The royal pardon

If that sounds like a plan plucked from a dusty shelf marked "Middle Ages", you're not far wrong.

Over the centuries an appeal to the monarch for clemency was the last chance of the condemned as they faced the gallows.

The power still exists today and is reserved for truly exceptional cases that can't be easily returned to court.

David Cameron's government issued a posthumous royal pardon, external in 2013 to Alan Turing, the World War Two codebreaker.

So the government could, at a stroke of a pen, "pardon" hundreds of convicted sub-postmasters.

What's wrong with that?

It's little more than a symbolic act: It does not quash the criminal conviction. Only the Court of Appeal can do that.

In 1993, the then Home Secretary Michael (now Lord) Howard posthumously "pardoned" Derek Bentley, who had been hanged in 1953. He said the execution had been wrong.

It took five more years for the Court of Appeal to separately rule the teenager should never have been convicted of murder in the first place.

So while a pardon is recognition by the state that there has been an injustice, it does not wash away the stain of criminality. And that's why MPs supporting post office campaigners say many of the scandal's victims would not be happy with that solution.

Option Three: Speed up existing appeals

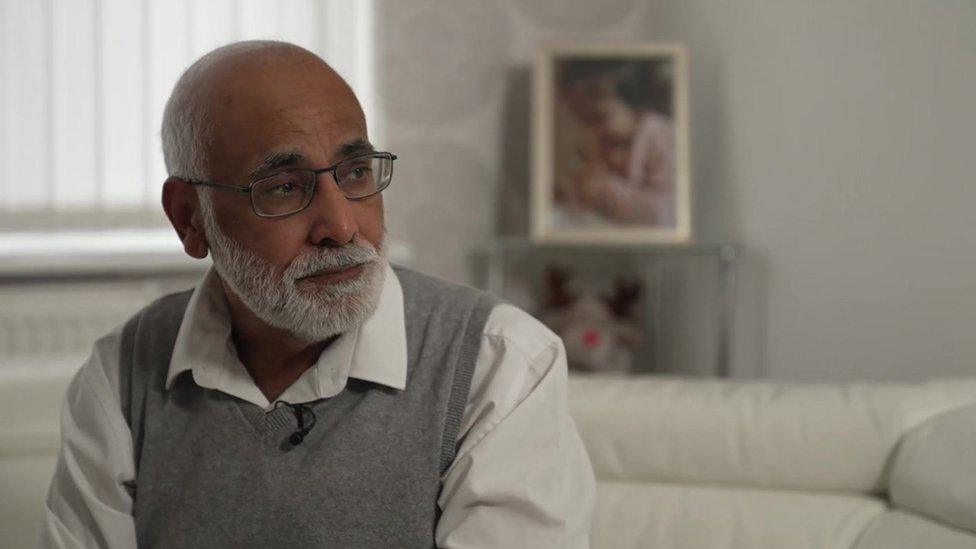

Postmaster Parmod Kalia was sentenced to six months in prison after being falsely accused of stealing £22,000. His conviction was quashed but he is still waiting for compensation

The Criminal Cases Review Commission sent 42 Post Office cases to judges after an earlier ruling had finally shown the Horizon system was flawed. The Court of Appeal exonerated 39 people in one go.

Professor Graham Zellick, the CCRC's former chair, says this is the solution.

"Given the necessary resources, the CCRC could do this job very quickly, and the Court of Appeal could respond with equal expedition," he told the BBC.

"[The cases] have a common feature, and it isn't very difficult to identify what that common feature is. It is that the prosecution case depended largely, if not exclusively, on evidence obtained from the computer system.

"Once you identify that, the conviction is clearly, manifestly, unsafe, and has to be quashed. And that's why the Court of Appeal can deal with these cases very quickly once they're brought before them."

What's wrong with that?

Of the 157 Post Office cases the CCRC has looked at, it has rejected 50 applicants. The CCRC applies a controversial and strict legal test which essentially tries to guess what the Court of Appeal will rule - and so its critics say it too often rejects pleas for help.

Another problem is the Post Office itself. Many victims want it removed from the appeals process.

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has the power to take over the cases in England and Wales - but that could mean months of more work as its lawyers read into hundreds of cases.

However, a top CPS team could select a small basket of cases for the Court of Appeal's judges to consider so they could set clear rules for how to deal with all the others more quickly.

Lord Thomas told the BBC he did not understand why it had taken so long for cases to come back before judges - but they would be entirely capable of handling all of the cases, if everyone worked together.

"We've got a system of independent judges whose duty it is to ensure justice is done and speedily," he said.

What about Scotland and Northern Ireland?

Deirdre Connolly says she had to repay £16,000 after being wrongly accused of stealing from her post office in County Tyrone

Scotland has its own criminal law system. The Post Office did not prosecute cases there as it had no power to do so. It handed its evidence over to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service - which then charged and prosecuted the suspects.

Similarly, in Northern Ireland, the police investigated and the Public Prosecution Service (PPS) pressed charges.

In 2020 the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) wrote to to 73 potential victims. So far, only 16 people have come forward and only two convictions have been finally overturned.

So while the CPS could be presented as an "independent arbiter" in England and Wales, there could be a real confidence issue in Scotland and Northern Ireland if the victims of the scandal are being asked to trust some of the same people who they blame for destroying their lives in the first place.

What about compensation?

Alan Bates was one of the main claimants who brought a case against the Post Office and says victims should be compensated quickly as "people need to get on with their lives".

Some sub-postmasters were never prosecuted - they can claim compensation covering the money they were forced to pay the Post Office when Horizon's errors led to accusations they had lost thousands of pounds. Many of their cases are unresolved.

Some of that group sued the Post Office - and their damages pay-outs are being dealt with separately.

It more complicated for people who were convicted of a crime. Quashing their conviction is the key to unlocking an offer of £600,000 no-questions-asked compensation - and that's why time is of the essence.

Critics of the UK's miscarriages procedures say the entire system is deeply flawed, making it very difficult for any victim of a wrongful conviction to be truly compensated.

BBC iPlayer - Panorama - The Post Office Scandal

This Panorama special tells the story of those whose lives were utterly devastated, reveals the damning evidence that was kept from them and investigates how and why the Post Office, a multinational tech company and the government covered up the truth for so long. (UK only)

Related topics

- Published9 January 2024