The chilling sound that signalled death for IRA 'informers'

- Published

Claire Dignam's husband Johnny was killed by the IRA for being a suspected informer

Of all the sounds that still echo in my memory from 50 years of covering the conflict in Northern Ireland, one above all still haunts me.

It's not the sound of bombs and bullets but the banging of a pan.

On recordings made by the IRA's notorious Internal Security Unit (ISU), that noise was the signal for suspected informers to begin confessing they had been working for the "Brits".

The tapes were delivered to families as alleged proof of their betrayal. The penalty for the informers was - as Martin McGuinness, the IRA leader at the time, told me - "death, certainly".

These chilling recordings are crucial evidence in a seven-year police investigation known as Operation Kenova, external. Its interim findings will be published later this week.

Kenova's focus is the activities of the British agent codenamed "Stakeknife" - real name Freddie Scappaticci - the army's most highly placed source at the top of the IRA.

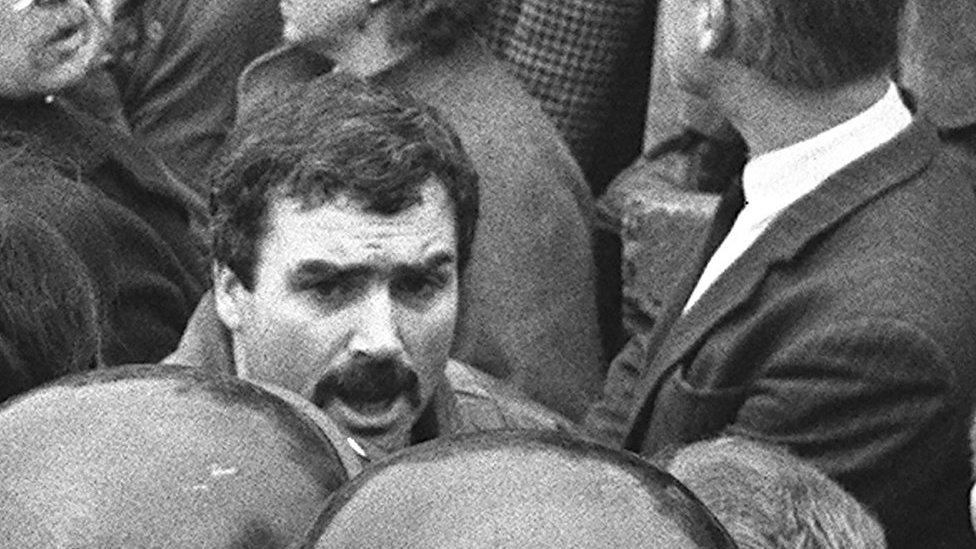

Freddie Scappaticci pictured at an IRA funeral in 1987

Scappaticci, who died last year, was the personification of the dirty war secretly fought between Britain's intelligence agencies and the IRA.

In addition to spying for the British army, he was also the ISU's chief interrogator, in which role he is believed to have been involved in 17 murders.

Kenova is also examining the legacy of Stakeknife and the ISU - the dozens of grieving families whose loved ones were interrogated as suspected informers and then brutally murdered by the IRA.

"This investigation now gives those victims, those family members, the opportunity to tell their story," said Jon Boutcher, the former Chief Constable of Bedfordshire and now head of Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), who oversaw Kenova for seven years. He has been succeeded by the former head of Police Scotland, Sir Iain Livingstone.

Our Dirty War: The British State and the IRA

Secret killer and super-spy: the Stakeknife inquiry leads Peter Taylor to revisit the brutal covert war between Britain and the IRA. Chilling tapes and victims reflect the horror.

Watch on BBC iPlayer (UK only) or BBC One Northern Ireland at 22:40 on Tuesday 5 March.

It will also be shown across the UK on BBC Two at 23:15 on Thursday 7 March.

The most egregious example of this undercover war came to light on 1 July 1992 with the discovery of three naked bodies, covered in bin bags, dumped on lonely border lanes in what was known as the bandit country of south Armagh. They had been interrogated for nine days, confessed to being informers and then been shot through the head. This was why the ISU became known as "the nutting squad".

When I learned about the bodies at the time, I knew I had to hear, and if possible, get hold of the tapes of their so-called confessions to try to piece together the jigsaw of the dirty war. It took several months of tense and secret negotiations before the IRA was prepared to let me listen to them.

I was hidden under a blanket in the back of a car and driven to an abandoned cottage in south Armagh, where masked and armed IRA men played me sections of the tapes. I had no doubt they were genuine and carefully edited to excise the interrogators' voices.

One of the three suspected informers was Johnny Dignam, a 32-year-old IRA member and former Republican prisoner from Portadown. Shortly after his murder, I went to see his wife, Claire, who was pregnant with the daughter he would never see. She could not believe her husband was an informer.

"I can't see him working for the police," she told me. "I couldn't believe it, knowing Johnny and living with him. He didn't die for what he believed in. He didn't die for the cause of Ireland."

Johnny Dignam fell under suspicion as an informer and was killed by the IRA in 1992

She showed me the last letter the IRA had permitted him to write. It was heartbreaking.

"I have only a matter of hours to live my life," he wrote. "I only wish I could see you and the kids one last time. I have done nothing but think of you. Tears are streaming down my face. Pray for me, look after my grave and visit when you can. Cherish this lock of hair and letter for the rest of your life."

At the end of last year, I went to see Claire again. She said she still had the lock of hair and the letter, but she did not keep photographs of Johnny around the house, because of the memory: "It just brings up dark, dark times and it never goes away."

Claire remembers the night Johnny disappeared.

"When he didn't come home that Saturday night, I knew something definitely wasn't right," she said.

"He always went in to kiss the two kids goodnight. And he didn't."

At this point she broke down: "If he had been working for security forces, they could have saved him."

No rescue effort was made - something that mirrored dozens of other cases in which suspects were interrogated and then murdered by the IRA.

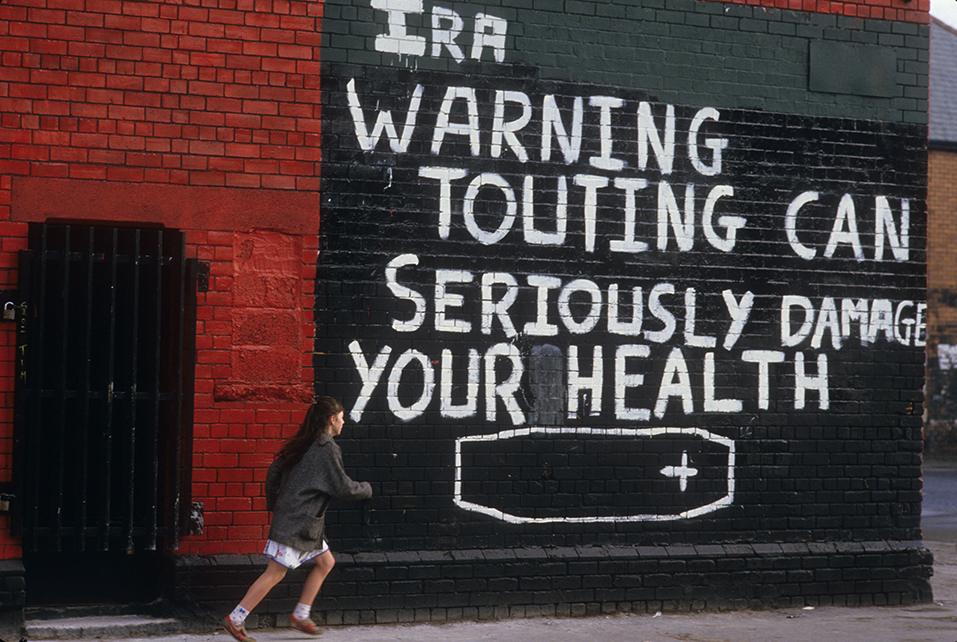

West Belfast 1985: The IRA was clear about the punishment for suspected informers or "touts"

Informers had been given assurances that they would be rescued if they were compromised. The former head of the British Army - and Northern Ireland veteran - General Sir Mike Jackson told me that these assurances were sincere, but that it could be "a very, very tricky operation" to spring an agent.

Only two or three rescues of suspected informers were ever successfully carried out.

I started to play Claire a brief extract from her husband's interrogation, having warned her it would be difficult to listen to. The sound began with the banging of the pan. It was too much.

"Oh no, I don't want to hear that," she said, standing up and putting her hands over her ears. "I don't know if I can cope with that." She then walked out of the room. I feared it might be the end of the interview.

A few minutes later, Claire returned, composed and ready to carry on.

"It's alright," she assured me, lifting her glasses to wipe away the tears. "Honest to God, don't worry about it."

Claire Dignam: "It's been a dirty, dirty war, and people like myself are suffering"

Claire thanked me for doing the interview. She said it was as if a great weight had been lifted.

"This is healing. It's healing for me," she said.

Claire described the trauma she has suffered for the past 30 years: "It's been a dirty, dirty war, and people like myself are suffering. I wish my kids had their daddy. I really, really wanted to live a normal life, so I put my kids first. It was hard but with help we got there and we're here now."

There was a further shock to come. Claire told me she had been approached after her husband's death by an army officer who tried to recruit her.

"He was a British soldier who was pretty high up and spoke with marbles in his mouth," she said. "He tried to ask me who I knew within the IRA. Why not come and tell us what you know?"

Claire said the officer offered her and her children a new life, but she said she was horrified: "I was still numb after my husband and then this happens. I really felt frightened for my life." The Ministry of Defence declined to comment.

I also revisited Dorothy Robb in Londonderry, whom I first met in 1986. Her partner, Frank Hegarty, had been killed, shot in the head in 1986. He was an IRA member who was suspected of revealing the location of a cache of arms from Libya.

Dorothy Robb says her partner was lured into a trap by the IRA

Frank had fled to England, but Dorothy said he was lured back to Northern Ireland by Martin McGuinness, who said he would be safe if he told the truth.

She told me Frank thought he could put up a convincing performance and convince his interrogators of his innocence. He failed, made a recorded confession and ended up as another body in a lonely country lane.

Dorothy said McGuinness rang - she recognised his voice - and told her she would never see Hegarty again.

"I was gutted," she said. "I just went into shock."

So when Operation Kenova reports this week, what do the relatives of the dead hope from it?

Dorothy says she is looking for "justice and the truth".

Claire says that she wants it to give answers to all the families, "no matter what those answers might be".

She says she has forgiven the people that killed her husband.

"If I don't forgive, I'll shrivel up and die," she told me. "But I do forgive them. I want to forget, but nobody can forget."