Homelessness: Number of rough sleepers up by a quarter in England

- Published

Rita has been sleeping rough at Paddington station for six months, along with her daughter

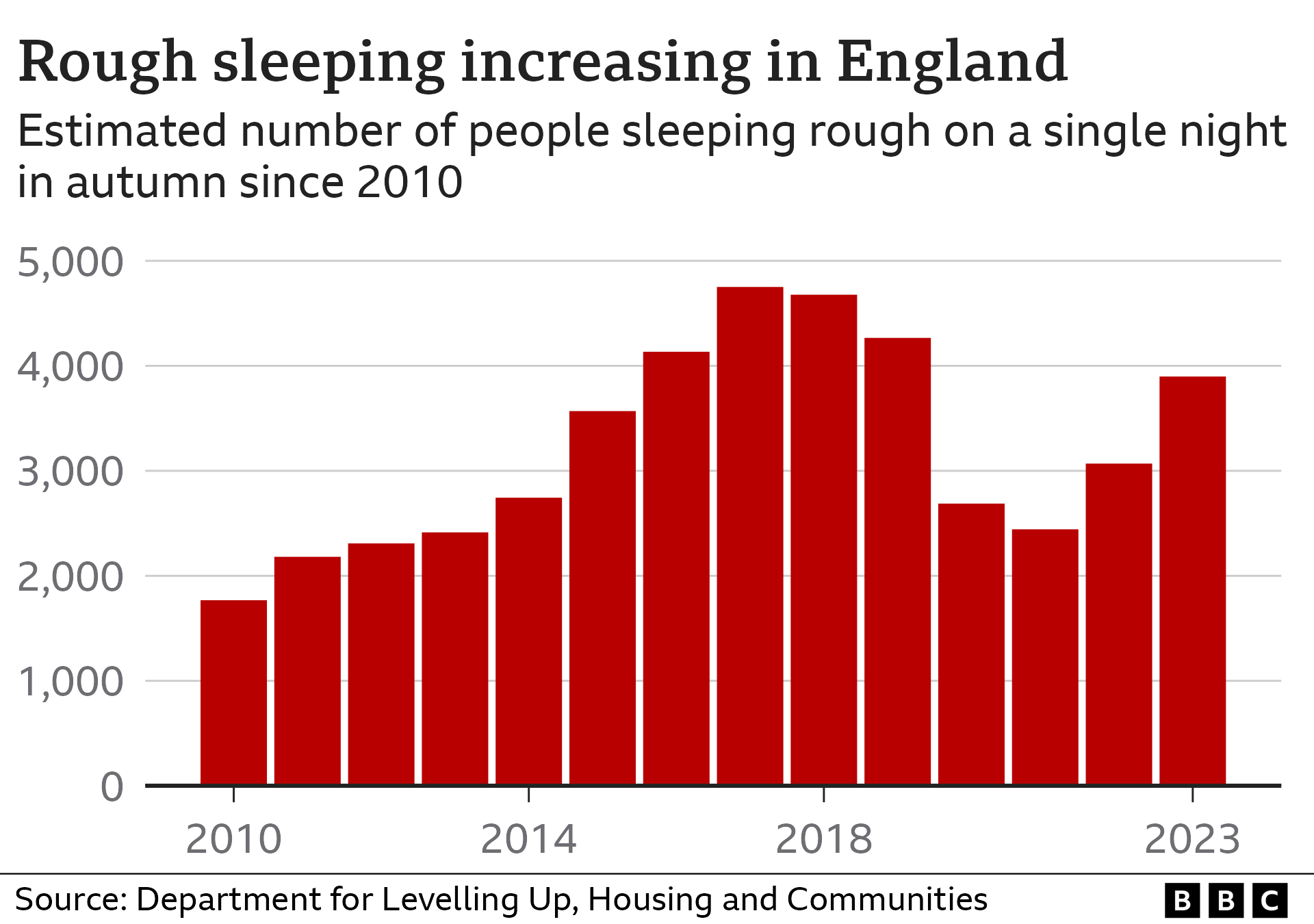

The number of people rough sleeping on a single night in England in the autumn of 2023 rose by 27% on a typical night from the year before.

Rough sleeping increased in every region, with London seeing the biggest rise of nearly a third.

However, rough sleeping is down 9% on 2019, before Covid-19 measures were temporarily introduced.

The government says it is spending £2.4bn helping rough sleepers and those at risk of homelessness.

A Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities spokesperson said: "Whilst we have made good progress and rough sleeping remains below pre-pandemic levels, there is more work to be done to meet our ambition to end it entirely, and we will continue to work with local authorities to help people off the streets for good."

Ministers had committed to ending rough sleeping by the end of this year.

The number of women sleeping rough was up by nearly a quarter, while the number of non-EU nationals rose by 87.7%.

More than half the total increase was driven by 20 local authorities, which made up 7% of the total areas.

Paddington's rough sleepers

The largest increase in rough sleeping was seen in London, where there were 1,132 people last year compared with 858 people in 2022, an increase of 32%.

On a recent evening, about 40 rough sleepers bedded down at Paddington station. The group included at least 10 women, attracted, said some, by the presence of both staff and CCTV.

Among them was 66-year-old Rita, who has been sleeping across a row of chairs in the station for six months, alongside her 38-year-old daughter. Born in the UK, she lived in France for many years but said she returned to London after losing everything in a scam.

"We try to find a seat before anyone else does. We're now lucky that we have a sleeping bag, we didn't have one until October. I go to sleep around 12:30am and wake up about 3:30 or 4am," she says.

Joseph, a rough sleeper at Paddington station

Amid tannoy announcements for late-night trains to places like Oxford and Reading, her daughter RD said: "It was scary, the first night, especially as women. But after a little while, you get used to the movements of people."

The staff are mainly kind, they say, and the rough sleepers in the waiting area look out for each other.

The area alongside Platform 12 is the warmest, says Joseph, 50. There are 24-hour toilets too, but the seats in that section have more armrests, making it harder to sleep. More people are on the floor, wrapped up in blankets and sleeping bags against shop doorways.

"There are thieves everywhere when you are rough sleeping, so I always sleep with one eye open," says Joseph.

Rough sleepers at Paddington station

'Everybody said no'

On a recent night outside Manchester's town hall, outreach workers counted 81 rough sleepers.

Most were refugees, recently granted the right to remain in the UK, but without anywhere to live. The Home Office has been trying to reduce the immigration backlog, but also cut the cost of accommodating them in hotels.

It has meant thousands of people have descended on both councils and charities seeking support.

Many of those sleeping under the arches of the town hall are from Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. Several showed BBC News copies of letters they had received, documents that both confirmed their right to remain and also to evict them from their Home Office accommodation.

Outreach workers counted 81 rough sleepers outside Manchester town hall

An Iranian woman in her mid-40s, who asked not to be identified, has been rough sleeping for 15 days after being evicted from her property. "It's not easy sleeping outside with a lot of guys who are all homeless," she says.

The council could not help her, she adds, and she struggled to find anywhere in the private rented sector. "I called everywhere, landlords, [posted] messages on different apps. Everybody said 'no, we can't accept you'."

Earlier this week, the woman, who is studying at two separate colleges, had a breakthrough. A landlord says he will let her stay for three months and she can move in this weekend.

"I was so happy. I explained my situation and assured him I would be a good tenant and try to pay the rent. I now just have to find some money."

The sheer number of refugees is leaving most local authorities across Greater Manchester struggling to cope. Salford Council said it has 291 people waiting to access A Bed Every Night, a scheme helping rough sleepers in the area.

The scheme has added an extra 200 beds until the end of March, bringing the total to almost 800, but it is not enough. The leader of Manchester City Council wrote to the government last week requesting an urgent meeting to deal with "the growing crisis".

Public services 'stretched to breaking point'

Charity manager Jan Drew says the system is overwhelmed

Since November, up to 60 people a day have sought help, wrote Councillor Bev Craig, with three-quarters of them having travelled to Manchester from elsewhere in the UK, "stretching public services and voluntary sector services to breaking point".

The Loaves and Fishes drop-in centre in Salford has seen soaring demand for its meals, showers and laundry facilities in recent months.

While many people get 28 days to leave their Home Office accommodation, Jan Drew, one of the charity's managers, says some people are evicted with just a week's notice.

"As well as trying to get your life on track, if you are then asked to leave somewhere within seven days, and go into a system that's already overwhelmed with numbers, it's difficult to manage your life," she says.

At the Loaves and Fishes drop-in, people can get a hot meal, have a shower and access benefits advice

Like many other places, Manchester is suffering from an acute shortage of affordable properties, creating blockages across the system.

Those who were moved off the streets and into hostels are often struggling to find suitable properties to move on to, leaving more people sleeping rough.

A worker at a different charity said some clients had moved as far away as Darlington and Gloucestershire to access suitable, affordable housing.