Absolute poverty: UK sees biggest rise for 30 years

- Published

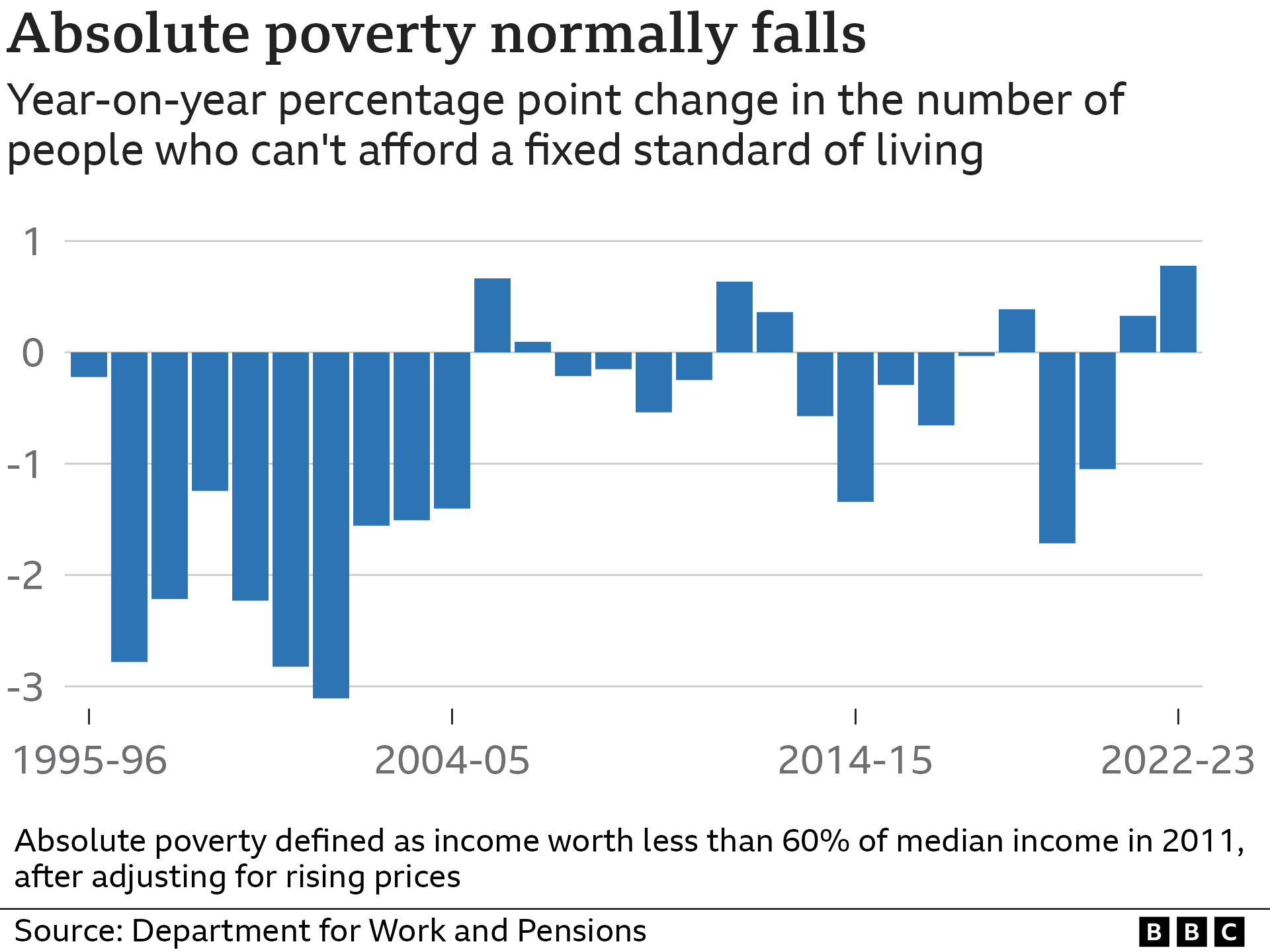

The energy price crisis caused the sharpest increase in UK absolute poverty in 30 years, new figures show.

Steep prices rises, following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, meant hundreds of thousands more people fell into absolute poverty.

The figure jumped to 12 million in 2022-2023, a rise of 600,000.

This means the rate of absolute poverty in the UK now stands at 18% - a rise of 0.78 percentage points.

Absolute poverty is the measure used by the prime minister when describing the government's record.

Even more families would have fallen into absolute poverty had it not been for government support like the Cost of Living payments.

Work and Pensions Secretary Mel Stride - whose department compiled the figures - pointed to the government's "biggest cost of living package in Europe, worth an average of £3,800 per household".

The government says that without these measure the increase would have been three times worse.

Mr Stride said the government's "unprecedented support prevented 1.3 million people from falling into poverty in 2022-23".

He also pointed to rising pensions and benefits levels this year, which will be on top of the 10% increase in both that came into effect just after these figures were collected.

Quarter of children in absolute poverty

The level of absolute poverty among pensioners barely changed on the year and remains at one of the lowest levels on record.

Pensioners were eligible for extra cost-of-living support like the £300 top-up to the Winter Fuel Payment.

But the number of children and of working-age adults in poverty each rose by about 300,000 people.

In these figures, a quarter of children were in absolute poverty.

The two percentage point rise in the rate of child poverty is the highest since at least the mid 1990s.

How is poverty measured?

There are two main measurements of low income used by the government. Income is counted as the money a household has to spend after housing costs are taken into account.

Absolute poverty measures how many people this year cannot afford a set standard of living. The Department for Work and Pensions currently defines it based on the living standard an average income could buy in the year ending in March 2011. If your income is 40% below this, after adjusting for rising prices since then, you are classed as living in absolute poverty.

Relative poverty is the number of people whose income is 40% below the average income today.

True picture on living standards of the poorest is worse

Someone who is in "absolute" or "relative" poverty may not be able to afford a living standard that might be expected in a rich economy like the UK.

But that does not mean they need a food bank or are unable to heat their home.

When you look at these types of poverty, the increases are more stark.

"Official income statistics have understated the true increase in deprivation during this period" says Sam Ray-Chaudhuri of think tank the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

He points out that the rate of food insecurity rose from 8% of individuals to 11% and the proportion unable to heat their home more than doubled from 4% to 11%.

Even pensioners saw an increase in the number unable to heat their home adequately, even though the headline measure of poverty fell slightly.

And the number of people who said they used food banks in the last month rose from 0.9% to 1.5%.

Labour said the statistics were "horrifying" and contrasted their record on reducing child poverty with that of the Conservatives.

"The Conservative government crashed the economy and unleashed a cost of living crisis, pushing families across the country into poverty" said shadow employment and social security minister Alison McGovern.

The figures were a "wake-up call moment", according to the Liberal Democrats.

"This is a devastating rise and behind these numbers will be stories of children going hungry and families unable to heat their homes," said the party's Treasury spokesperson Sarah Olney.

Shirley-Anne Somerville of the Scottish National Party said: "We are doing everything in our powers and limited budget to tackle poverty in Scotland."