Growth of the 'big four': For and against

- Published

Residents living near supermarket developments, farmers supplying the stores and bodies representing workers and the retail industry reveal how they feel about the expansion of the so-called 'big four' - Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury's and Morrisons.

The residents

The BATS group have a regular street stall in Belper to campaign against Tesco

In 2007, Tesco proposed an 80,000 sq ft store on the site of an old Thorntons chocolate factory in Belper, Derbyshire.

A group of residents decided to get together to campaign against the store and created the Belper Against Tesco Superstore (BATS) group.

Tesco owns the land, which is near the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site, but has yet to submit a planning application to build the superstore.

Andy Minion, spokesman for the group, said the town already had three supermarkets and feared another one, on the edge of Belper, would encourage shoppers away from the high street.

"We have a number of Tescos... in Heanor, Alfreton - they are both edge of town developments," he said.

"You look at what was once a perfectly OK high street in the town and the shutters have gone up, they are full of charity shops and empty units."

However not everyone is against the Tesco development. A Facebook group called Belper for Tesco has 600 members.

One member, Deborah Sanders, said: "I thought Belper was trying to move forward and having Tesco and other shops is the only way."

Plans for a new Sainsbury's in the market town of Louth, in Lincolnshire, were turned down by East Lindsay District Council in December 2009.

Keep Louth Special, a group set up in 2008 to campaign against the council selling the town's cattle market to the highest bidder, which it feared would be a supermarket chain, spoke against Sainsbury's plans.

Alan Mumby, chairman of Keep Louth Special, said the group was not "anti-supermarket" but wanted to protect Louth's high street and its independent traders.

"There are too many instances all over the country where town centres have died," he said.

The farmers

Tesco has set up a group to ensure the price it pays farmers for milk covers production costs

Andy Bloor, 57, runs a 310-acre dairy farm in Dutton, Cheshire, which supplies 1.5m litres of milk to Tesco each year.

He is chairman of the 800-strong Tesco Sustainable Dairy Group, which was formed four years ago to ensure farmers received a price for their milk which covered production costs.

He said Tesco provided him with a rolling 12-month contract and paid enough to ensure he could invest in his business.

"We are getting a better price and we have confidence that if we invest they [Tesco] will still be in the market for our milk," he said.

"With any business, you cannot just stand still because costs are going up. If you do not re-invest and improve we will end up going backwards and slowly the wheels of the business will come off."

He said the price was constantly reviewed and would be looked at again in January.

David Handley, chairman of UK campaign group Farmers for Action, feels differently about supermarkets. He blames them for the decline of the British agricultural industry.

The dairy farmer said they were ignoring their corporate responsibility by not fairly paying farmers for their produce, which was putting many out of business.

"The dairy industry has shrunk by nearly 50% in eight years, the pig industry in the UK is virtually decimated," he said.

"Fruit and veg growers are getting less and less.

"As we get less and less home-produced food the pressure comes on where it's going to come from."

He said farming had declined since the mid-1990s, which he said was the last time farmers could earn a decent living.

"Multi-national retailers of the likes of Tesco, Walmart [which owns Asda], I hold them totally to blame for this," he said.

"They are the ones that control the purse strings in the supply chain."

Tesco said it had local buying teams dedicated to working with small, regional suppliers to sell local produce in stores.

The union

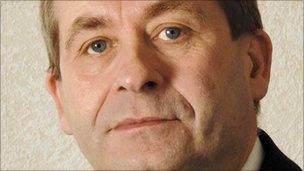

John Hannett said the growth in supermarkets was welcomed news

The growth in the big four supermarket companies is welcome news for the union which represents many of their employees.

Usdaw, which has nearly 400,000 members ranging from check-out staff to supermarket section managers, says it has seen people who had given up all hope of ever working again have their fortunes reversed by a new store opening in their town.

John Hannett, the union's general secretary, said: "A lot of the supermarkets that have opened (have been) in areas that are run down and there are people who are long-term unemployed, including many with learning difficulties, who have been given opportunities they would never have been given.

"You can imagine how important these jobs are in these times.

"If you go into some of the areas that I've been to where people have located supermarkets they've been scarred by long-term unemployment. The idea of an interview alone was daunting and all of a sudden they're being viewed as somebody with something to offer."

The union believes further expansion by the big four should be encouraged.

"There are areas where planning permission is rejected or there's strong local community opposition [but] when these stores open you often find the reaction that was there dies down," Mr Hannett said.

"From my perspective if it brings good jobs and keeps people employed, at the end of the day that's what people want. We can only see a positive developing out of this, especially in those kind of communities where there really are no prospects for people."

The retail sector

The BRC said it was shoppers who had the power in retailing

The British Retail Consortium (BRC) says in the past 10 years the year that saw the biggest growth in supermarkets was 2001.

It says expansion among the big four is driven by customers, not corporate greed.

BRC spokesman Richard Dodd said: "If you look at the figures for the last 10 years from 2000 to now, in fact overall grocery space rose each year by between one and two per cent which is obviously very low growth.

"[It is] modest growth and actually surprisingly consistent over the years.

"Anyone who is saying supermarkets are actually growing more rapidly than ever is actually wrong.

"Why is supermarket floor space growing at all? The answer is all of this is driven by customers. The people who have the power in retailing are the customers."

The BRC, which represents the top nine biggest food retailers, says local opposition to new supermarket developments usually evaporates when the new store opens and customers flock through the doors.

"Quite often there's a small but vocal minority who make their feelings very well known and usually generate some publicity and they come out with all these lines about it's not wanted here and it's going to kill the high street," Mr Dodd said.

"The supermarkets have got long experience about where would be an appropriate place to open a store. The retailers generally get these judgements right.

"Most of the store opening that is going on now either is the convenience store or it's about bringing the particular name to an area where it's under-represented at the moment.

"If customers genuinely don't want the store they won't use it and it won't last five minutes."