Future of farming: Mega-dairy or theme park?

- Published

Original plans for the Nocton super dairy would have seen it house 8,100 cows

"It'll be a factory farm, a kind of prison for cows."

Some of the activists are quite wound up about it. "The cows will be so miserable... it'll be an Orwellian nightmare... "

They were talking about plans to build the UK's first ever mega-dairy, close to the village of Nocton in Lincolnshire.

One of the protesters unfurled a banner showing a distressed cow staring out from behind iron bars.

"I think the big four supermarkets are behind this" he said, "so they can make cheap milk... cheaper... cheaper... cheaper".

The Nocton dairy hopes to sell milk to the supermarkets but none of them has signed up.

New research compiled by BBC news teams in conjunction with the Panorama programme has revealed that planners approved applications from the 'big four' supermarket companies for at least 577 new stores across the UK in the two years between 1 November 2008 and 1 November 2010.

And as the supermarkets continue to grow, and continue to search for new ways to offer cheap food, the way our food is produced is changing.

For those of you unfamiliar with the concept of a mega-dairy, Nocton will be around 30 times bigger than the average UK dairy farm; the cows will be kept largely indoors; and aside from producing record-breaking quantities of milk, it will also produce 20 million gallons of cow excrement each year which will somehow need to be disposed of.

Theme park

I can not blame some of the locals for being worried. But the difference is, I've already visited a mega-dairy in the US - the very one which the Nocton site will be modelled on.

I didn't go alone. I took with me a traditional UK dairy farmer called Tony Gillett, a man who'd just been forced out of business by rising production costs and falling prices.

Mega-farms are already in operation in Indiana

He's not unusual, a dairy farmer goes bust in England and Wales every day. If anything, Tony had every reason to be resentful of what he was about to experience.

As we entered Fair Oaks farm in Indiana it was more like a theme park than a dairy farm. You can milk plastic cows, dance to a milk rapper, watch milk-fuelled skeletons race up a wall.

Tony and I were among the 400,000 who visit Fair Oaks each year. And Tony was looking a little bewildered.

An hour later, we were standing at the business end of the farm, in the middle of what the owners call a "dairy-go-round" an enormous rotating carousel where the cows are milked. Everything here is on a mega-scale. Each cow produces 80 pints of milk a day, and there are 40,000 of them.

Tony stared up at the row of black and white faces and broke down.

But not for the reason I expected. He examined their skin, their behaviour, the way they responded to milking, and concluded they were healthy and happy, and he was emotionally overcome.

He was not worried about the futuristic appearance of the place. He said it was immaculate and that the cows would only produce milk in such quantities if they were well looked after.

But what about the fact the cows at Fair Oaks never go outdoors, isn't that unnatural? Tony said UK herds have to be kept indoors much of the year anyway, and the people behind Fair Oaks claim even if they opened the shed doors, the cows would wander back to their air-conditioned units.

Back in Lincolnshire, the dairy farmer behind Nocton, Peter Willes, has compromised on his original plans. He has already halved the size of the mega-dairy he originally wanted, from 8,000 to just under 4,000 cows, and he has now designed a "loafing paddock" where they can go outside and enjoy the English countryside, when it is warm enough.

Economies of scale

A decision about Nocton will be made in the new year.

Dairy farming is not the only business going mega to try to achieve economies of scale as prices are driven down at the big four supermarkets.

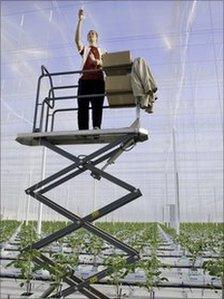

At Thanet Earth in Kent, they have the UK's largest hi-tech greenhouses. Workers pick two-and-a-half million tomatoes a week, and even when it is snowing outside six different varieties are ripening inside.

Workers pick two-and-a-half million tomatoes a week at Thanet Earth

Its boss, Christopher Mack, says the supermarkets "can't deal with hundreds and hundreds of small suppliers… They are clearly attracted to dealing with a few large scale producers who can deliver consistent quality".

Of course, the supermarkets have their organic ranges and premium brands which can be provided by smaller suppliers, but it clearly reduces their costs if they have fewer, larger producers in some sectors.

Think of a milk tanker having to visit dozens of small dairy farms to fill up each day. A mega-dairy would be a one-stop shop, saving on fuel and man-hours, and probably meaning greater margins for both the supermarket and the dairy farmer.

As Peter Willes says: "Why should agriculture be any different to any other business? At the end of the day although we're looking after animals and care passionately about them, this still is a business…. other industry has either gone bigger or unfortunately they've gone out of business."

The campaigning chef and food writer, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall says all this intensification is "costing us in our landscape... our food culture, this is changing the quality of the land that we walk on, potentially even the quality of the air that we breathe. I mean, this is big stuff."

But how much are the supermarkets really responsible? They are giving us affordable food, and a greater variety of it than we have ever had before.

They are giving us convenience and the opportunity to buy healthily. They are only responding to what we want.

It would not make business sense for them to do anything else. So in the end, it is us, the consumers, who are behind what some are calling the UK's second agricultural revolution.

BBC Panorama's Supermarkets: What price cheap food? will air on BBC One at 2100 GMT and will be available on BBC iPlayer.

- Published20 December 2010

- Published18 November 2010