Bloomsbury museum preserves London's foundling stories

- Published

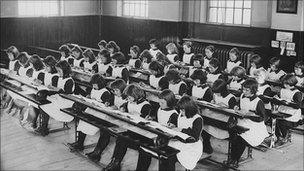

These boys were among the thousands of foundlings schooled in central London and in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire

The personal stories of abandoned children in the first half of the 20th Century have been collected by the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury.

Preserved in audio interviews, photographs and film, the memories of these former foundlings stem from childhood.

During this time they were educated at premises adjacent to the museum in Brunswick Square or at a special school in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire.

Together they weave tales of family separation, a spartan education and the search to make sense of the outside world in the inter-war period.

The collection is housed in a new exhibition, which hears from more than 70 pupils.

The youngest is 68 and the oldest 98.

It is part of a four-year project of preservation, designed to complement the archives of the Hospital, London's first home for foundlings.

Set up as a charity in 1739, it gave more than 20,000 children an education after spending their early years with foster mothers.

Today its care work and support continues as children's charity Coram.

The BBC has been given access to some of the interview material in the exhibition.

The picture that emerges from the stories in Foundling Voices, external is of a world almost unrecognisable to our own, separated by a distance of a mere 70 years.

Arrival at school

Ruth: I was dressed in my best and handed my teddy and my doll and the coach came to the cottage door and I climbed on board with my foster mother.

The memories of 74 former foundlings feature in the exhibition

As we got further from home and nearer to school I asked the question, 'will I be able to come home for my dinner?' And she said 'no' but didn't enlarge on it, and almost as we got into the school gates I said, 'I will be able to come tonight, won't I?'

And as we got off the coach the boys were shepherded one way, the girls the other. And she said, 'be a good girl' and she kissed me and she was gone.

John: The abiding memory is that one day, our dormitory was upstairs, a big dormitory with over 30 children in and there was two lines on the outside and two lines in the middle and I remember standing there and I thought 'now I'm all alone. It's me against the world'.

And that's the first time I ever thought, y'know, that I was somewhere different, that I was in a school, I wasn't with my foster parents. I was on my own...

On foster family relationships

Sam: My foster mother was the loveliest person I've ever known. I keep saying it but she spoilt me something terrible.

Do you know what she used to do? I was an avid reader, I loved reading and she used to buy me comics, not the comics you see nowadays, these were comics called The Wizard, The Rover, The Hotspur.

And she had them all stacked up for me, she spent a fortune. I come back from holiday, come home and run indoors and they were all stacked up in piles. 'Thanks mum!' up there and straight away reading. I loved it.

Sylvia: I know it was hard for mum because apparently after she'd taken us back for the first time, you know, she was so upset when she got back home and saw all our toys and clothes.

I don't remember it but it was hard for her. My foster sister Marion, her daughter, she told me. She said 'we were all crying'. She said, 'dad and me and mum'.

Going into the world

Constance: I had a small case which the Foundling Hospital had given me. And I had one small case, and everything that I owned went into this one small case.

Philip: ...toothbrush, flannel, towel, change of underwear, boot-brushes or shoe-brushes, polish, handkerchief and that was about it.

At the age of 15, foundlings went into the outside world, either to the forces or into service

John: ...the only clothes we had when we left school was our school uniform, and all the other boys came in their civilian clothes and we had no civilian clothes, so we went from school uniform straight into Army uniform. From one uniform into another.

And I remember the first night there, a lot of sobbing going on in the dormitory, in the Army hut, where boys were missing their mums and were homesick.

But our boys weren't homesick 'cos we were used to being disciplined or whatever, and we had nothing to cry about, so we listened to the other boys sobbing as they went to sleep, missing their home. We had nothing to cry about.

Ruth: There weren't many options - you could become a shorthand typist or work in a shop or a factory and I couldn't visualise what any of this was like. What was an office? Everybody seemed to know what they were doing in a shop.

And I always wondered how I would make that leap. It didn't occur to me that there was training, that you would be taught. Just this fear of not knowing what it was about.

It was a very real fear, I wanted to stay in my comfort zone. I look back and I think, 'this is why I became a nurse...' There were rules, there was a uniform. It was a hiding place, a comfort zone.

On relationships

Lydia: I was so innocent, I was so innocent. The first time a boy kissed me and it wasn't a passionate kiss but it was a kiss that I thought was really quite nice, I went into the toilet in the office where I worked.

I knelt down on the floor and I said 'please God don't make me pregnant'. We didn't know a thing.

Foundling Voices runs at the Foundling Museum in central London to 30 October 2011.