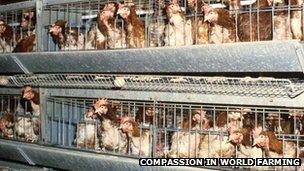

Battery hens 'deserve a second chance'

- Published

The British Hen Welfare Trust has rehomed nearly 300,000 former battery hens

Jane Howorth came to the telephone out of breath and needing a drink of water after spending a windy December afternoon collecting 450 former battery hens from a Devon egg farmer.

The hens, which would otherwise be sent for "processing" for chicken pies and soup, have been found new homes and many will live out their days as treasured pets.

They are the first batch of 1,200 hens which will be collected from the farmer as he restocks with barn hens to comply with an EU-wide ban on battery cages which comes into force on 1 January.

The ruling, which the government said British farmers have spent £400m complying with, has created a busy time for Mrs Howorth and the British Hen Welfare Trust (BHWT), which she founded seven years ago.

'Penguin stance'

The charity expects to rescue about 2,000 "ex-bats" a week until the end of the year as it holds special rehoming days across the country.

"But they're not all committed to homes and there are a lot more out there if people want to rehome them," Mrs Howorth said. "We've got the volunteers willing and able to collect the hens - they all deserve a second chance."

The charity said most UK egg farmers had moved to "enriched" cages, which have more space, a nest box and perches, but it believes two to four million hens in the soon-to-be-banned "barren" cages will be slaughtered.

Mrs Howorth said battery hens were generally slaughtered after a year of laying and it would probably be considered too stressful for the birds, and uneconomical, to move them to different cages.

A former personal assistant, her passion for hens began when she moved from Berkshire to a home with some land in Chulmleigh, Devon, in 1995.

"I went to get 12 battery hens and felt sorry for them and collected three dozen. There was one particular hen which had a stance like a penguin. I think other hens used to bully her and so I separated her," she said.

The trust founder said the hen was "very communicative" and responsive.

"I built a relationship with her and it made me realise there is a lot more to them than chicken dinners and popping out eggs," she said.

She named the chicken Vicky, short for Victorious, hoping it would pull through. Under her care, the lopsided-bird lived for a further 18 months and laid five dozen eggs.

Battery cages will not be used in Britain from 1 January

Mrs Howorth said ex-bats made "excellent pets".

"People say they are so cheeky and endearing and affectionate," she said.

Kathy Freeman, 46, a freelance translator from Buxton, Derbyshire, rescued her first battery hens through the BHWT in November.

"Their combs, which are usually quite red, were very pale pink," she said. "They just look tired and like really, really hard-working birds, which they were."

Ms Freeman, who already owned three hens, was not sure the newcomers would survive as they seemed so delicate.

She was reluctant to give them proper names but their nicknames "Scrawny Neck" and "The Other One" have stuck.

'Life-affirming'

They spent the first few nights in an old cat basket under the stairs and laid eggs, even on the first morning.

"They soon gained confidence and I found knowing they were seeing wind, rain or sunshine every day afresh quite life-affirming," Ms Freeman said.

"Scrawny Neck" is now fully feathered

The hens have brought joy to her neighbour's grandchildren who have become frequent visitors.

"You would not think that a hen could have a personality, but they do and they're really easy to look after," she said.

The translator, who has whipped up the extra eggs to fill her freezer with quiches, added that Scrawny Neck had gained a plume of feathers.

The BHWT has rehomed nearly 300,000 ex-battery hens and Mrs Howorth said the cause had "completely taken over my life".

"When they come out into the open for the first time they are bewildered but soon start scratching and stretching and taking dust baths and thoroughly enjoying themselves," she said.

"Their natural behaviours start to return within seconds and it's most magical. I never get tired of seeing it."

Farmers 'vulnerable'

The charity has focused on building trust and relationships with farmers and convincing consumers that battery farming has resulted from a demand for cheap eggs.

Battery hens enjoying their first taste of freedom

"We have really begun to bridge the gap between welfare and commerce," Mrs Howorth said. "Our ethos is to support the industry and try to influence consumers and say to farmers 'we're not here to vilify you'."

Meanwhile, egg farmer Duncan Priestner believes the government's £400m figure is a "conservative" estimate of cash spent by UK farmers preparing for the EU ban.

Mr Priestner, 50, has replaced cages and improved standards at his farm near Altrincham, Greater Manchester, over the past three years.

"It has been a very, very tough time," he said. "On the financial side, our farm has spent £2.5m which is the biggest debt in our history and will probably take the rest of my working life to pay off."

He said he was happy with the improved welfare systems but concerned UK farmers would be "vulnerable" to cheaper imports because 13 of the EU nations have not yet complied with the battery hen ban.

However, the government insisted it had taken steps to protect farmers by gaining agreement from supermarkets not to sell eggs from illegal cages or use them in their products.

- Published6 December 2011

- Published13 June 2011