Swedish company comes to run Suffolk free school

- Published

- comments

The Swedish company that inspired Michael Gove's free school programme is set to run a Suffolk school

The owners of the first free school in the country to be run by the Swedish company that inspired Education Secretary, Michael Gove, external, have been meeting parents in Suffolk to tell them more about themselves.

IES, external (Internationelle En) was chosen by parents who're setting up the Breckland free school in Brandon in Suffolk.

A study last year found that the number of pupils in Swedish free schools had increased from 20,000 in 1995 to 96,000.

The thinking was that allowing a greater freedom of choice for parents would drive up standards.

So there was an outcry last year when a study by Stockholm University, external claimed that free schools hadn't had much of an impact on driving up standards in Sweden's schools.

Many free schools produced their own figures showing that their students were doing much better.

Educational standards

"It's very hard to properly answer this question," says Professor Jonas Vlachos who helped write the report.

"People keep using different data and because we have a decentralised grading system, schools set their own grades so it's hard to compare like for like."

"But I think it is fair to say that there is some indication that free schools have led to a slightly slower decline in educational standards in Sweden."

Most of the free schools opened in the last 10 years are run by for profit companies like IES, external which will run the free school in Brandon.

Five out of six made profits of more than half a million pounds.

It's this private involvement in education, making a profit at the expense of the Swedish tax payer, that makes some people uneasy.

"There's a fixed amount of money (from the state) for every student," says Professor Vlachos.

"So in order to make a profit you have to cut down on costs.

"The student/teacher ratio is highest among the for profit schools. They don't have as many teachers, they also tend to hire less experienced teachers."

He says that municipal school teachers have worked for an average of 18 years while free school teachers have worked for six years.

"Maybe they have great ways or organising things but you may suspect it's harming quality," says Professor Vlachos.

Passion for learning

IES, who are only one of many providers of free schools in Sweden, are coy about how they make their money but we did notice that many of their staff were young and possibly newly qualified.

Nevertheless, the company denies it cuts back on quality.

"We are passionate about education," says IES's chief executive, Peter John Fyles.

"Our ethos is about working with young people and developing them to the best of their individual ability."

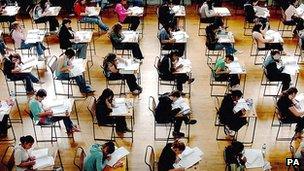

Supporters believe that students' results could be better under the Swedish system

The company runs 17 schools in Sweden. Its students' results are above those of other free schools in Sweden and there is a long waiting list.

"Our sheer numbers tell us we're doing a very, very good job.

"We have 62,000 pupils waiting to get into our schools, so we must be doing something right," says Mr Fyles.

"It's not about making money.

"It's about delivering quality - that's what parents always ask about - they don't focus on money, they want to know what we can provide for their son and daughter."

Professor Vlachos' study also found that free schools have led to greater segregation between communities.

That is unlikely to be an issue in Brandon but in Luton where there has been talk of establishing free schools, local politicians have expressed concern about this very issue.

There are now more than 700 free schools in Sweden, they are established and everyone accepts they're here to stay.

It's what our government would like to see here.