Body donation: Learning from the dead

- Published

In most cases a donated body is used over a single academic year

Each year hundreds of people in England sign on to body donor registers.

That decision can lead to them being dissected and scrutinised by medical students and researchers long after their death but still they volunteer themselves up for the good of science.

Unlike the millions who would be put off donation by the thought of being used as a training device, Graeme Ellis wanted to help others in the event of his death.

At first he opted for organ donation but was told he was not a suitable candidate due to a number of health conditions.

He is now on the body donor register at De Montfort University's medical school.

The 45-year-old from Leicester has diabetes, high blood pressure and suspected angina but while his health prevents him from donating organs he believes body donation will help others by training the doctors of the future.

He said: "I want to help people after I've died.

"I walked into the university's information centre and asked them about it and explained that I couldn't be an organ donor.

"They said my diabetes could be helpful when I'm alive as well because they are doing a study about diabetes and exercise so they've put me on their study programme.

"It's an extra plus point that I can help people when I'm still on earth."

He said family and friends had been reluctant to hear about him donating his body to the university but they understood it was what he wanted.

"I just want to give something back to the world," he said.

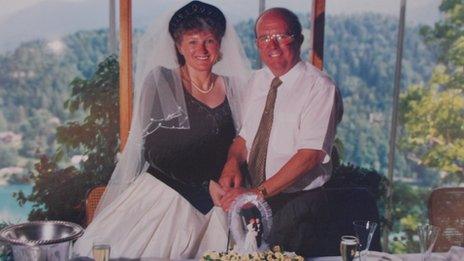

Wilfrid Kirkham wanted his body to go to a useful purpose

Wilfrid Kirkham died seven years ago at the age of 66 from pulmonary fibrosis.

He and his wife Christine had both decided to donate their bodies to medical science before his death.

Lit a candle

They were put in touch with Keele University because it was the nearest institute accepting donations at the time although they lived in Croston, in Lancashire.

Mrs Kirkham said: "We didn't want to be buried and we didn't have strong family ties, we wanted our bodies to go to a useful purpose."

A memorial was recently installed at Keele University to honour body donors

She said the only part of the process she was not prepared for was the affect the delay between her husband's death and his funeral would have on her.

She said: "We never talked about that bit and the grieving.

"We talked about what happens when they finish with a body but we never talked about the grieving time.

"After 12 months you're trying to get your life together and you get a call to say they've finished with the body - it was like he'd died again."

She explained although she did not regret the donation she thought it was important that relatives talked about how delaying the funeral could affect them.

Staff from the university attended Mr Kirkham's cremation service and a few years ago the university organised a memorial service for all those who had donated their bodies.

"Every name was read out and a student lit a candle for each person," she said.

"The chapel was packed and all the students were there. It was very emotional and so touching to see the respect they had for the donors."

The university also named an award after Mr Kirkham which is presented to the student who has done the best work in anatomy each year.

She added: "I get a lot of comfort from that, it carries on his name, which is wonderful."

As another symbol of thanks the university has recently installed a memorial for those who have donated their bodies to the university - 133 since the department of anatomy opened in 2003 with a further 1,500 on the university's donor register.

Body donation is overseen by the Human Tissue Authority (HTA) but donations are made to individual medical schools.

There are about 30 institutions around the UK which accept body donations, with people usually choosing the nearest one to their home or to an area they are originally from.

Mr Ellis was told he was not a suitable organ donor

People are referred to an institution through the HTA's website or by their GP, solicitor or local authority.

Each university that accepts donations has an anatomy bequeathal officer, except for London universities which share a central contact point.

The officer talks to the person wishing to donate about what is involved and sends them forms to sign if they want to take it further.

After another discussion their details are put on file and they are advised to tell their family and their solicitor or GP.

In most cases the body is used over an academic year but can be held by the university for up to three years under current legislation.

Mike Mahon, director of anatomy at Keele University's School of Medicine, said there were two main reasons why people wanted to donate - to help others and to find a use for their body when they no longer needed it.

He said: "Quite a few people say they'd like to put something back into society. They may have had help from the medical service and they want their body to be used for something useful.

"We have all kinds of people wanting to donate - there's no typical donor."

- Published23 July 2010