Pupil Premium's first year: Grade A or could do better?

- Published

- comments

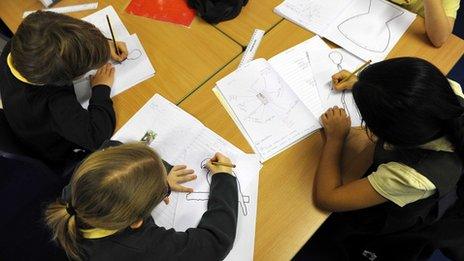

Some schools have spent their pupil premium on one-to-one reading sessions for children

It's the coalition policy many Lib Dems are most proud of.

They believe the pupil premium has the potential to transform the lives of some of the most disadvantaged children.

But after its first year, there is mixed evidence about whether the premium is going to deliver what they hoped.

The idea is pretty simple.

Head teachers get extra money from the premium, based principally on how many of their children qualify for free school meals.

There are other factors which can boost a school's premium level too such as the number of children with special educational needs, and whether they have pupils whose parents are in the armed forces.

But principally, it's about directing extra resources to schools in the most deprived parts of England.

Raising expectations

Schools have had around £480 per pupil this year, with that rising to £600 from September.

The hope is the extra money can raise expectations and performance and make these pupils more socially mobile.

And there are schools which can tell you just how much difference the money is making.

South Bank Community Primary near Middlesbrough is in one of the most deprived parts of the country, and more than half of its pupils qualify for free school meals.

It's had £60,000 from the pupil premium in the last year, and the head teacher says it's made a massive difference to the school.

Helen Hall has spent it on employing a staff member to work one-to-one with children on their reading.

Class sizes have been kept down, and money spent on other projects to develop the children.

Helen Hall's quite clear she couldn't manage without the extra money.

She said: "The pupil premium has afforded me that flexibility to respond to the needs of my children.

"Without it, I am not sure my results would be at the level they are at, and without it my children would not feel motivated, feel confident or be able to challenge themselves to raise their aspirations to reach their potential."

Budgets cut

There are clearly winners then, but in theory there should be no losers where pupil premium is concerned.

Nunthorpe School is academically successful but gets limited funding from the pupil premium

The money is in addition to a school's base budget so even if a school has only one child that qualifies they will get extra funding.

But it's clear that not every head teacher feels better off.

Many schools have seen their budgets cut, and often it seems they don't feel the pupil premium has made up for that.

A recent survey by the National Association of Head Teachers, external found only 14% of heads thought their schools now had more money.

Around a third felt they were neither worse nor better off, and more than half felt their school had suffered a funding cut despite the premium.

A few miles away from South Bank, Nunthorpe is one school which has had to manage with less money.

Some staff have been made redundant and resources are not as plentiful.

The pupil premium has helped to a certain extent but as only around one in 10 students get free school meals, the funding hasn't been enough to compensate for the shortfall.

Head teacher Debbie Clinton admits her school is in a more affluent area, but doesn't see why her students should be punished for that.

She said: "The issue is a child is a child and all children have an equal legal entitlement to equality of opportunity within the education system.

"Whilst we have every sympathy with those schools with larger numbers of families defined as deprived, we actually feel that the ball park is not a fair one and hasn't been for some time."

Academic success

And then there is the question of how much difference money can make.

Nunthorpe School is one of the most successful academically in the country, and Debbie Clinton believes that the leadership and ethos of a school make more of a difference than resources.

And a study by Durham University, external does cast doubt on whether the pupil premium will make the kind of difference the Lib Dems are hoping for.

Although schools are being assessed on what results they're getting from their funding, they are free to spend the money pretty how much they want.

But when the Durham study looked at some of the most common ways schools are spending the money - educational trips, cutting class sizes, employing teaching assistants - it found little evidence they were likely to raise standards.

Instead the more effective techniques were often less easy to cost. They included better feedback for pupils.

It could be some time before we know whether the pupil premium has made a difference to children

Professor Rob Coe, external, one of the authors of the report, says it's far from clear that throwing money at more deprived pupils will change their prospects.

He said: "Over the last 10 to 15 years spending in education has increased hugely, and yet we have seen no huge increase in attainment, perhaps no increase at all.

"I think the research on spending and its relationship with genuine improvements in learning is very mixed.

"Sometimes it can have a benefit, but not necessarily so, and it really depends on what the money is spent on."

There's no doubt some schools do value the pupil premium and believe it's making a difference.

It's easy to be enthusiastic when you watch the South Bank pupils enjoy their reading.

But the reality is that this story has many more chapters yet.

There may be many more twists and turns before we find out whether it'll have a happy ending for the children and the coalition.

- Published14 May 2012

- Published1 May 2012

- Published12 December 2011