Hyperbaric chambers: Not just for the bends

- Published

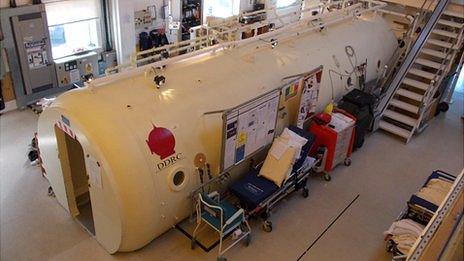

The centre's main chamber is used to treat up to nine people at time

The Diving Diseases Research Centre in Plymouth has had its work highlighted recently, after members of a family in Cornwall with carbon monoxide poisoning were treated in its hyperbaric chambers.

The chambers are most associated with treating divers with decompression sickness - the bends - if they surface too quickly, resulting in nitrogen bubbles forming in blood.

Although it was founded in 1980 "with divers in mind", staff at the charity, which treats people with 100% oxygen in pressurised chambers, are not just standing around waiting for divers to get in trouble.

The charity has six chambers - four in Plymouth and two at a sister facility in Newport in Gwent - and Plymouth's chambers can treat up to 10 patients on a weekday with a variety of conditions.

'Bump starts'

The treatment involves patients spending two hours in a 100% oxygen atmosphere in a sealed chamber usually pressurised to the equivalent of 14m (45ft) under water, or 2.4 atmospheres, centre medical director Dr Christine Cridge said.

It could be pressurised to the equivalent of 30m (100ft), she added.

Patients breathe in pure oxygen instead of the 21% found in normal air and the pressure increases the amount of oxygen that dissolves into the bloodstream and the body's tissues.

Patients are given oxygen through helmets in the main chamber, the Krug

In the case of the bends, this results in nitrogen bubbles which form in blood being squeezed into a solution blood can absorb.

In carbon monoxide poisoning cases, the oxygen-rich environment "bumps" the poisonous gas, which prevents blood from absorbing oxygen, off the oxygen-carrying red blood cells.

In other cases, the pure oxygen may not be a cure in itself for what is being treated but could often be a "piece of the jigsaw puzzle", Dr Cridge said.

Such cases included helping patients with skin, bone or tissue conditions after their body's own healing process had "stalled", she said.

Conditions treated include chronic non-healing wounds, such as ulcers as a result of diabetes, through to radiotherapy-damaged tissue or bone in cancer patients, or even flesh-eating bugs which do not like an oxygen atmosphere.

In the case of flesh-eating necrotising fasciitis, Dr Cridge said: "We can't resurrect dead tissue, but we can prop up what remains and bump-start its healing."

"Bumping" or "bump-starting" are phrases used a noticeable number of times by Dr Cridge, who first got interested in the field after time with a diving club at university.

Such bump-starting can see pure oxygen providing extra fuel for the immune system's white blood cells and the body's building blocks for new cells.

"In certain patients, it can encourage growth", she said.

Another use of the oxygen treatment has been assisting radiotherapy by "feeding" tumours, which are often faster growing than other cells, making them making them easier to target, she added.

The Krug

As to the actual treatment, if anyone has the idea such chambers are little bigger than a medieval iron maiden, the centre's largest, the Krug, easily defeats preconceptions.

Built in 1990, the chamber, named after the company that designed it, is 6m (20ft) long with a 2.4m (8ft) diameter.

It can hold up to 12 people, though it is only used to treat a maximum of nine, with two staff also inside to monitor the process.

Emergency cases can be wheeled straight in, as it can cope with intensive care cases and offers "more room to work in", Dr Cridge said.

Staff can pressurise the chambers to the equivalent of 30m under water

"One older patient commented it was bigger than a World War II tank. We've also been told it's the size of a small bus.

"They are best known for treating the bends and people have turned up with swimming costumes before, not realising they'll be dry."

However, you do not just fill a 25 cubic metre chamber with 100% oxygen.

While the entire chamber is filled with compressed air, the oxygen is actually ingested via transparent plastic helmets which are sealed around the neck.

"It means people can read or watch a DVD," Dr Cridge said.

Dealing with boredom is a serious consideration. While a diver might have just two or three sessions, other patients may be in for two hours a day, five days a week, for up to eight weeks.

The centre also has two smaller 3m (10ft) by 1.8m (6ft) diameter chambers, which employ helmets.

Its smallest chamber resembles a 2m (6ft 6in) long transparent plastic tube which is about 1m (3ft 3in) in diameter.

Unlike the other chambers, this is filled completely with oxygen, allowing treatment for anyone who cannot use the helmets because of wounds or other considerations.

The centre also has wound treatment rooms with specialist staff, as well as facilities for training in hyperbaric medicine.

It also works with universities on research projects.

As to divers who have been treated at the centre for what can be a fatal condition, Dr Cridge said: "It rarely puts them off.

"At least 90% of divers will go into the water again, with many of them asking as they're being wheeled in or out: 'When can I go back?'."

- Published30 January 2013

- Published24 January 2013

- Published14 October 2011