This House - can a play reveal the whips' dark arts?

- Published

- comments

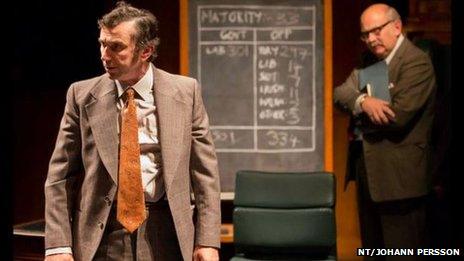

Actors Phil Daniels and Vincent Franklin as Labour whips in This House

It's the part of government we don't see - the engine room some say.

But now you can get a chance to get a glimpse inside the whips' offices - or at least a recreation of them.

The National Theatre's This House takes place largely in the government and opposition whips' inner sanctums as we follow the political machinations of the 1970s.

No majority

This was a time when the whips - the MPs in charge of maintaining party discipline and winning parliamentary votes - certainly earned their salaries.

Between 1974 and 1979, Labour was in government, but for much of the time it had no majority.

That gives playwright James Graham a surprising amount of drama to work with.

Nick Brown was Chief Whip under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown

Indeed, the very survival of the Labour government depends on the whips delivering. Fail and they know Margaret Thatcher is ready to banish them from office.

But just how real is this drama? To find out I invited someone with inside knowledge to see it on stage.

Newcastle East's Labour MP Nick Brown did not enter the Commons until 1983, but he knows a thing or two about the whips' office.

He was Tony Blair's first Chief Whip in 1997 and Gordon Brown's last in 2010.

Legendary tales

His challenge was rather different to that facing his 1970s counterparts though.

He had a whacking Labour majority to work with in 1997, and it was still a secure one even at the end of New Labour's terms in office.

But when he entered the engine room the tales of the Wilson and Callaghan whips were already legendary.

In This House we see Labour MPs literally dragged off their death beds to maintain the government's majority.

Seventeen Labour MPs - including one whip - died during the period, and the play suggests some at least were victims of the need to turn out at all costs.

At one point, ministers are flown back from Northern Ireland in atrocious weather to prevent defeat.

Nick Brown said: "All that is true. In the case of the two ministers, all civilian flights had been stopped. But they were flown back for the vote through a ferocious storm even though it put them and the military personnel who flew them back in great danger."

Class divide

The play also highlights the class divide between Labour and Tory whips.

Labour's are largely working class with little education beyond school. The Conservatives are ex-public school, ex-Oxbridge and ex-military.

And even in his time, Nick Brown says that divide was still there.

He said: "The only difference was that our whips had started going to university by then, but there was still a very different atmosphere between the two camps - with the opposition often from more privileged backgrounds. It was a rivalry, but there was respect there too."

Crucial to Labour efforts to stay in power were the whips' relations with the "odds and sods" - the Liberals, and the nationalist and unionist parties in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Unlike today there was no formal coalition, but bar-room deals had to be done to secure their votes.

Nick Brown had no need to cultivate such alliances. Labour's 1997 majority was 179 and even by the end of Gordon Brown's time it was over 60.

Actors Rupert Vansittart and Tony Turner as some of the "odds and sods" Labour had to make bar-room deals with

But he still liked to meet the smaller parties to gauge their views and keep them as potential voting allies so recognises the need to build relationships across the house.

Serial rebels

In This House though, the Labour whips have as much trouble with their own side.

As well as dealing with the mentally-unstable John Stonehouse - who disappears, reappears and then resigns - there are serial rebels who threaten to bring the government down.

That was something Nick Brown could certainly relate to. As we watched, he joked that dealing with MPs as Chief Whip wasn't too far removed from dealing with livestock in one of his other roles as agriculture minister.

He said: "Whips are really the government's business managers, and the real challenge is to get legislation through in the face of adversity. Your crucial relationship is with the Prime Minister who has to trust you to deliver."

And in This House the Labour whips do deliver almost to the end.

Only in the dying days of office in 1979 does Labour lose the vote of confidence that ushers in a general election and 18 years of opposition.

But it's in the twists and turns of the previous five years, and the pitting of wits between the rival offices that makes the play edge-of-the-seat entertaining.

It's creatively staged and also very funny, and avoids getting bogged down in the rather rarefied gentlemen's agreements between the rival offices.

Real people

Playwright James Graham interviewed many of the participants during his research and that shows.

Actors Reece Dinsdale and Charles Edwards as opposing Labour and Conservative whips

And unlike the monstrous Francis Urquhart in House of Cards, these whips are real people who want to win but not ultimately at all costs.

In the end it's an act of compassion by a Labour whip towards an ailing colleague that the play suggests caused the loss of the crucial vote.

Nick Brown said: "It works as a terrifically-entertaining piece of theatre. It takes a very complex and taut political situation and breaks it down, and makes it understandable even 40 years on.

"The human side comes across very strongly. Everything in it may not literally be true, but it has a sense of truth about what it's like to be in the whips' offices, and what it must have been like then."

And of course This House throws the spotlight onto the politicians we as the public should never see. The whips who have to get things done.

But would Nick Brown have liked or loathed the challenge of governing without a majority?

He thinks for a second, and then with a hint of relish, he says: "Absolutely everything they did, we would have done I'm sure.

"Yes, I think I would have enjoyed it."

This House runs at the National Theatre in London until 15 May, and a performance will be shown at cinemas around the UK on 16 May.

- Published5 March 2013

- Published29 September 2010