The Beeching report: How railway cuts divided Yorkshire

- Published

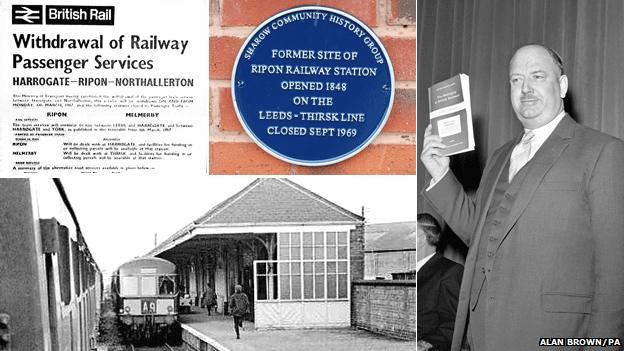

Dr Richard Beeching's report meant the end of hundreds of stations

The publication 50 years ago of an explosive report on the future of Britain's railways was a watershed moment for a country which could proudly lay claim to the world's oldest rail network.

Drily entitled The Reshaping of British Railways, the document would soon be better known as the Beeching Report after its author, Dr Richard Beeching - the chairman of British Railways.

In 1963, Britain's railways were running at a loss of £140m a year. And Dr Beeching had made it his job to "make the railways pay".

With just half of the network's 7,000 stations carrying 98% of the traffic, the doctor came to a shocking conclusion: the withdrawal of more than 2,000 stations and 250 train services.

Few places would escape the effects of the "Beeching axe" and, 50 years on from the report's publication, those effects can still be seen, not least in Ripon, a small city on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales.

Ripon station, which closed in March 1967 as a result of the Beeching Report, has now been converted into luxury flats and is at the centre of a modern estate

On the outskirts of the city, famous regionally for its 1,300-year-old cathedral, Station Drive looks much like any other suburb. But among the identikit houses one building stands out as being of unmistakeably grander design - a relic of a bygone era.

Half a century ago it was Ripon railway station - a link between the cathedral city and the outside world. But after Beeching's axe fell passenger services stopped in 1967, and freight followed in 1969. Today, the station has been transformed into luxury flats.

'Act of vandalism'

Back in 1963, Dr Beeching had promised: "In all our planning, we haven't forgotten that railways are there to serve people. We haven't forgotten the human side."

In 2013, Mick Stanley would beg to differ. As newly-elected Mayor of Ripon and a member of Ripon Chamber of Trade, he passionately believes the station's closure was a massive mistake.

"It was nonsensical and we can still feel its effects 50 years on. It never really made much sense and I can understand that the anger is still there about Ripon losing its link," said Mr Stanley.

"Getting rid of the railways was one of the acts of vandalism of the 1960s. If we still had a station, we would be getting more people in to Ripon, I don't think there's any doubt about that at all."

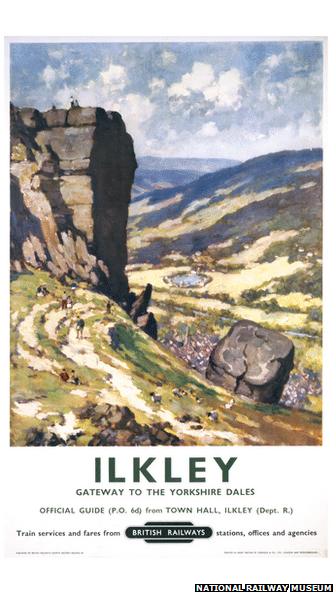

It is a different story just 30 miles away in Ilkley, West Yorkshire - a town famous for its moors and its spa waters which were enthusiastically consumed by sickly Victorians.

Although Ilkley station was earmarked for closure by Dr Beeching, in 2013 it remains a thriving rail terminus - though, in a nod to the 21st century, much of the old station building is now taken up by shops and a pizza restaurant.

Ilkley's station and rail link were saved after successful lobbying by the Ilkley Rail Defence Association, predecessor to what is now Wharfedale Rail Users' Group (WRUG).

Peter Johnson, WRUG secretary and himself a former railwayman, said losing the station would have imposed a "dead hand" on the town.

"The people who were already here would have stayed, but you wouldn't have got the same number of newcomers coming in. It would, perhaps, have become a town of genteel old ladies taking tea in Betty's Tea Rooms," he said.

"What the railway has enabled Ilkley to do is to help it keep up to date with changing public demands and provided a good place to bring up families with good travel connections and a good place for people to visit."

In Ripon, Mr Stanley said that while about 300,000 people visit each year, not to mention other nearby attractions such as Fountains Abbey, the loss of the city's station in 1967 meant it had failed to fulfil its potential as a tourist hotspot.

old11.jpg)

This train, pictured at Ripon on 4 March 1967, was one of the last services to run through the station before it closed to passengers for good later that day

Richard Taylor, chairman of Ripon Museums Trust, said the lack of a rail link to the city often sparked disbelief among potential visitors.

"It does put people off. If we invite people here for a conference or something they ask, 'When is the train to Ripon?' We have to say that the last train from here was in 1967.

"People can't believe that a place like this doesn't have a station."

Link 'crucial'

That disbelief is shared by shoppers braced against the wind in Ripon's picturesque market square.

Ripon resident Carol Harrison said people remained "very cross" about the lack of a station.

"We can't get anywhere. There's no link to the north, to Harrogate, to York. We feel very cut off - it's like an island," she said.

And Estelle Fulford, also from Ripon, said: "It's disappointing that we don't have a station. There is a frequent bus service... but it does affect people's lives. It's a bit of a faff."

The contrast between Ripon and Ilkley post-Beeching could not be clearer. In fact, as Mr Johnson pointed out, the town's rail link to Leeds had proved so popular that not only was it electrified in the 1990s, but extra trains were also recently introduced to cope with demand.

In the booking hall at Ilkley station, young mother Ruth Kitcher, with lively three-year-old Evangeline and nine-month-old Phoenix in tow, supported Mr Johnson's view of the station's positive contribution to Ilkley life.

"The station's really important. It's great to be able to take the kids to town. It's far easier than driving and we're always taking them out on trips as they get bigger. We go to Leeds, up to the Railway Museum in York and on seaside trips as well," she said.

"It's really quite crucial. I would never choose to live in a place that didn't have a station, purely for reasons of convenience."

And had Ilkley fallen foul of the Beeching axe in 1963, pensioner David Smithson, from Ryhill near Wakefield, said the lack of a station in the spa town would affect his lifestyle today.

"It would have made access to the Dales for me very difficult as it shortens the journey to the Dales. I'd prefer trains any day of the week. I guess it would have affected a great many people if the station had closed," he said.

Whether Beeching is seen as a hero or a villain - or something in-between - is coloured by the experience of individual towns or cities.

While it is easy to blame Beeching for the impact of his infamous axe, even former railwaymen like Mr Johnson admit "large number of closures were necessary".

'Billions in subsidies'

While Ilkley station was sold as the gateway to the Dales on this 1960 poster, it faced closure just three years later

But for people in the city the effects of the Beeching Report certainly live on.

Norman Robinson, a visitor from nearby Harrogate, put it bluntly: "If there was a railway station it's highly likely we'd use it, what with the bloody traffic the way it is.

"On some days it's horrendous - just come here on Thursdays for market day and take a look."

And even for those towns and cities which enjoy a rail service post-Beeching, there is still plenty of reason for rail users to be unhappy, according to campaign group TaxPayers' Alliance (TPA).

Robert Oxley, TPA campaign manager, said: "Beeching may have intended to make the railways much more efficient, but he would not have many reasons to be cheerful if he were alive today.

"Taxpayers are still having to foot bills worth billions every year in subsidies, with the current system of franchising offering very poor value for money."

While the "bad old days" of a state-owned railway were over, Network Rail remained "a highly inefficient quango", added Mr Oxley.

"There is room for far more competition which would deliver better service and better value for taxpayers."

- Published28 January 2013

- Published10 January 2012

- Published6 September 2012