Dambusters: Triumph and tragedy after the dams

- Published

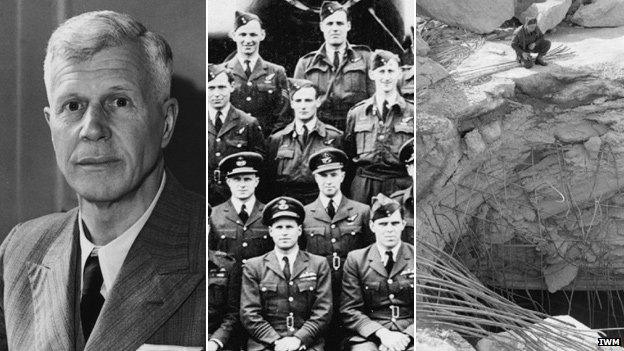

617 Squadron still flew the Lancaster, but abandoned low-level attacks after serious losses

Barnes Wallis and 617 Squadron formed a partnership which inflicted immense damage on the Third Reich

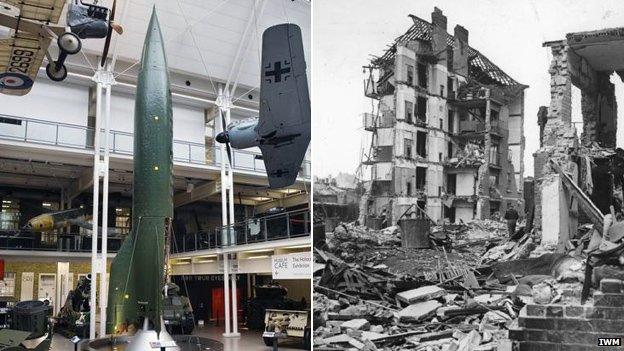

617 Squadron's Lancasters had to be adapted to carry the huge Tallboys and Grand Slams

Concrete bunkers for torpedo boats, which had resisted earlier attacks, were demolished by Tallboy

V2 rocket launches, which caused terrible damage to London suburbs, were limited by 617 Squadron attacks

The faces of all the air crew who took part in the Dambusters raid have been published for the first time, but what happened to the squadron after the famous mission?

The stunning success of Operation Chastise secured 617 Squadron and "bouncing bomb" inventor Barnes Wallis their place in history.

But in the weeks and months that followed - and in the face of further terrible losses - the partnership of expert flying and revolutionary bomb design unleashed a level of precision destruction on the Nazi war machine which surpassed what had gone before.

"The greatest achievement of 617 Squadron and Barnes Wallis came after the attack on the dams," says Dr Peter Preston-Hough from Wolverhampton University's War Studies department.

"Whatever the direct impact of that raid, its main legacy was to vindicate Barnes Wallis as a weapons designer, establish 617 Squadron and make possible what came after.

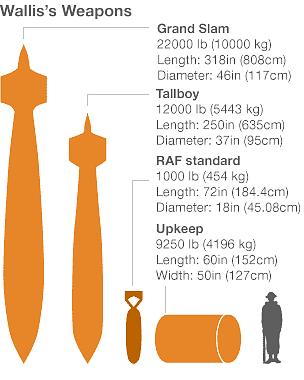

Barnes Wallis had for years believed the standard RAF 1,000 lb bomb was ineffective against big targets

"And what came after certainly saved thousands of civilian and military lives, may have saved the D-Day invasion and perhaps even shortened the war."

In the early hours of 17 May 1943, as news came through that the mighty Mohne dam - the first to be attacked with Upkeep - had been breached, the fiery head of RAF Bomber Command, Sir Arthur Harris, turned to Wallis and said : "I didn't believe a word you said when you came to see me. But now you could sell me a pink elephant."

But this was just the beginning. Barnes Wallis had plans for a new generation of bombs, unlike anything seen before.

For years before the dams raids, Wallis had told anyone who would listen (and many who wouldn't) the standard method of aerial attack - showering a target with relatively small 1,000lb bombs - was next to useless.

Wallis had a radically different, literally groundbreaking, concept.

The earthquake effect

Dr Iain R Murray, from the School of Computing at the University of Dundee, runs a website devoted to Barnes Wallis, external.

He says: "One of the key effects of the dams raid of May 1943 was that it proved Barnes Wallis's "earthquake" theory - that a big bomb exploding underground, or underwater, had a far larger effect than an explosion on the surface.

"Wallis believed the shockwaves from a large device which would slice tens of feet into the ground before detonating could undermine and damage larger structures which were almost invulnerable to standard 1,000 to 2,000lb bombs, which blew up on contact."

But even with his new, Dambuster-founded credibility, Wallis had a problem. His earthquake bombs were little more than sketches and calculations.

The leap from drawing board to battlefield would take months of testing and design to achieve.

And during that time 617 Squadron - now acknowledged precision attack specialists - would find the demands and sacrifices of war continued.

Charles Foster, Dambusters expert and nephew of raid pilot David Maltby, explains: "The RAF's top brass were not sure what to do with 617 Squadron after the raid.

"The debates went on throughout most of the summer of 1943 and it wasn't until September that the squadron was given a serious operation to perform."

The target was the Dortmund-Ems canal which carried large amounts of industrial raw materials. Like the dams raid, the attack would be at tree-top height.

"It was a disaster," Mr Foster says. "The first night it was attempted, David Maltby and his crew were lost in an accident while turning back after the mission was aborted.

"The following night, the attack force set off again and another six Dambusters were amongst the 33 personnel killed when five crews were shot down.

"Two more of the original crews were shot down later in 1943 and while one man was captured, 13 were killed.

"1944 would see the deaths on active service of five more Dambusters, including the Victoria Cross winning Guy Gibson."

Mr Foster highlights the immense price the Dambusters crews had paid: "Just 48 men out of the 133 who took part in the raid survived the war, just 36% of the total.

"This ratio is substantially below the survival rate for Bomber Command as a whole, where 70,000 out of 125,000 (56%) were alive at the end of the war."

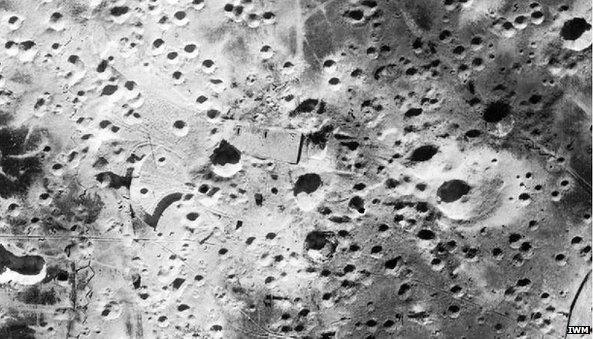

The V3 guns at Mimoyecques were sheltered by the concrete slab in the centre - smaller bomb craters pepper the site but Tallboy's 100ft (30m) craters are evidence of the decisive attack

During this time Wallis's new weapon had taken shape and been given a code name - Tallboy.

Dr Murray says: "The 12,000lb (5,443kg), 21ft (6.4m) bombs were aerodynamically-shaped pressure vessels, carefully designed to offer the largest explosive capacity while retaining the strength to hit the ground at supersonic speeds without shattering.

"Aluminium tails set at an angle spun the bombs as they fell, and combined with improved bomb sights, they were devastatingly accurate."

Vengeance weapons

From June 1944, Tallboy (and in the latter stages of the war the even larger Grand Slam) was used against an array of targets which had before defied the allies.

Huge bridges were flattened and deep railway tunnels collapsed, disrupting the movement of troops and equipment. Canals were burst, choking the supply of industrial raw materials.

Reinforced concrete U-boat and torpedo boat pens were shattered, crippling a threat to Allied shipping.

Even a battleship, the mighty Tirpitz, was blasted away, prompting headlines and a hot squabble with 9 Squadron over who had dropped the critical Tallboy.

Dr Murray adds: "These key targets had proved nearly invulnerable to conventional bombs, and only the large earthquake bombs could damage them, which they did to great effect - another legacy of the Dams Raid, and of the genius of Barnes Wallis who designed them."

But under the inspired guidance of a new commander, Leonard Cheshire, the combination of precision skills and revolutionary bomb design found its fullest use against the infamous V weapons.

The Vergeltungswaffen (reprisal) machines were designed to rain explosives down on Britain without the need for vulnerable bomber aircraft.

The V1 and V2 were jet and rocket powered missiles, while the V3 was a long-range 5.9in (15cm) calibre supergun, capable of hitting London from its position buried in cliffs on the French coast.

Mike Mockford is archivist at the Medmenham Collection, external, which covers the work of aerial photographic reconnaissance in World War II.

He says: "Aerial reconnaissance found the V weapon sites but for some time no one knew what they were.

"They were attacked on the principle that if the enemy had gone to such trouble to build them, they must be worth destroying.

"When their potential became clearer they became a priority on a par with D-Day."

Development and production of the weapons was delayed by conventional bombing, but the project continued remorselessly.

"Without air attack, up to 2,000 V1s, with 1,900lb (850kg) warheads, could have been launched every 24 hours," says Mr Mockford.

"Add to that the V2 and V3 attacks and the destruction could have been immense.

"Cities could have faced an onslaught to outstrip the blitz. Plans were drawn up to evacuate central London.

"Hitler hoped the V weapons would turn the war in his favour, even Supreme Allied Commander Eisenhower felt such attacks could have delayed D-Day by at least a year.

"And while the invasion of Europe went ahead before they were ready, the V weapons could have wreaked havoc on vital supplies stockpiled in channel ports."

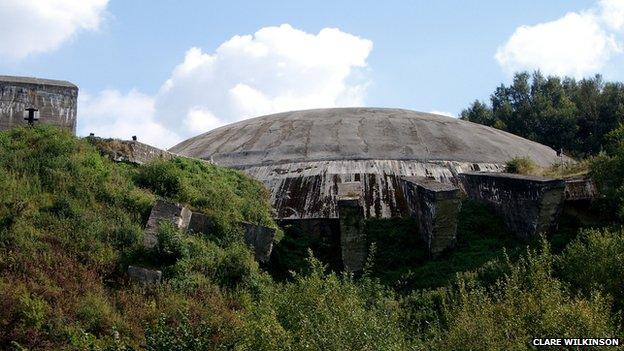

The 230ft (70m) wide V2 bunker at Wizernes was knocked off level and made unusable by Tallboy bombs

Dr Preston-Hough concurs: "The situation was critical and while the danger had been recognised, the weapons still had to be destroyed somehow.

"Buried deep in cliffs or covered by thick concrete, conventional bombs had no direct effect on the heavy sites, as the bunkers were known, but 617 Squadron systematically knocked them out."

Most spectacular of the heavy sites was a V2 assembly and launch facility, built into a quarry at Wizernes, near the French coast.

Its concrete dome, 230ft (70m) across, 16.4ft (5m) thick and weighing more than 50,000 tonnes, covered about 4.3 miles (7km) of tunnels.

On 24 June 1944, 617 Squadron Tallboys hit it so hard it ended up blown to one side and militarily unusable.

Unique legacy

"But the V3 site at nearby Mimoyecques, arguably the biggest threat of all, remained," says Dr Preston-Hough.

"It was designed to launch up to 600, 310lb (140kg) shells an hour at London and was built 330ft (100m) into chalk cliffs capped with massive concrete slabs.

"617 Squadron hammered it with Tallboys and many of the chalk tunnels collapsed, burying hundreds of people and crippling the facility."

After the war, Barnes Wallis worked on designs for fast jet aircraft but none were built.

617 Squadron continued to be a keystone of the RAF, becoming part of the nuclear deterrent force and later taking part in the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

But both are still mainly remembered, and honoured, for a partnership which did so much to limit the power of the Nazi aggression.

- Published18 July 2013

- Published17 May 2013

- Published15 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013