Did the 1960s ruin the cities of the East Midlands?

- Published

All three cities have their gems... and their eyesores

A band of intrepid crusaders strolls around the lost ruins of an ancient city with one question on their minds: can anything be salvaged?

They have not stumbled upon the crumbling remains of Atlantis or ancient Troy.

They are, instead, surveying the remains of the lost city of Leicester.

Like its near-neighbours, Nottingham and Derby, Leicester is more renowned for its high-rises than its half-timbered historic gems.

Yet tucked away behind the wrappings of concrete ring-roads lie Roman remains and ancient churches.

Derby's Edwardian Hippodrome Theatre should be the jewel in the city's crown, says the civic society

Now Derby, Leicester and Nottingham are making efforts to dust off their Georgian gems and medieval treasures.

But is trying to recapture the past a waste of investment for these three cities?

Or is there a chance their heritage revival could prove the tourist draw and economic boost many in the East Midlands would dearly love to see?

Derby

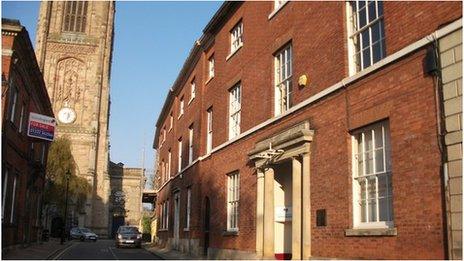

Derby's Cathedral Quarter has been "very well looked after" says the civic society

However, the development of Westfield has cast a "blot on the landscape" says Ian Griffiths, of the civic society

According to its civic society, Derby has its historic "jewels", but they are surrounded by "dereliction".

Like Nottingham and Leicester, 20th Century development left an unfortunate legacy as far as many are concerned.

Over the past decade, efforts have been made to reinvigorate the city's Georgian and Victorian buildings through a £200,000-a-year investment by the council and other partners, such as English Heritage.

But is it a case of too little, too late?

"I certainly wouldn't compare Derby, Nottingham or Leicester to York or Bath," said civic society member Ian Griffiths.

"Derby is my hometown but I feel it has been smashed up almost beyond recognition."

The old police station and magistrates' court ruin Derby's riverfront aspect, the society says

Mr Griffiths, whose family have lived in Derby since the 17th Century, points to culprits such as the city's ring road.

Its construction, in the 1960s, meant the removal of what he describes as Derby's "finest" Georgian square, St Alkmund's, and the historic St Alkmund's Church.

But he believes a more modern development has been responsible for irrevocably altering the city centre - the expansion of the Westfield shopping centre in 2007.

"Westfield is an appalling blot on the landscape," he said. "That big block has ruined the skyline of Derby.

"In addition, it was a huge blow to the independent retail in the St Peter's Quarter. Derby's planners should be ashamed of themselves."

The St Peter's Quarter and Green Lane areas are now looking increasingly neglected, said Mr Griffiths - and nowhere more so than the Hippodrome Theatre.

"The poor old Hippodrome," he said. "It should be the jewel in Derby's crown. It was a beautiful Edwardian theatre and needs to be revived."

Derby City Council said they are bidding for Heritage Lottery Funding to return Green Lane to its former glory and are working with English Heritage on the future of the Hippodrome.

There are, Mr Griffiths said, some historic highlights in the city. The Cathedral Quarter, which benefited from the English Heritage restoration scheme, is one of them.

"The streets in that area are very vibrant and well looked-after," he said. "And Derby's old Market Hall is almost European in its style and has a wonderful atmosphere."

But talk of a wide-scale heritage revival rings strangely, he said, in a city he feels has neglected its past for so long.

"I think it is too late, sadly, for Derby to become known for its heritage," he said.

Nottingham

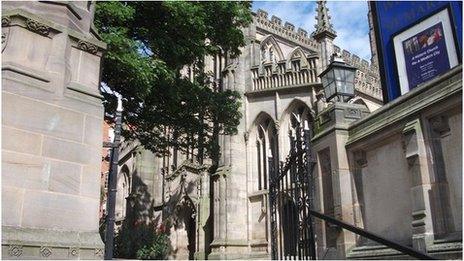

The Lace Market, including St Mary's Church, includes a host of architectural gems, say the civic society

The Broadmarsh Shopping Centre meant the loss of one of Nottingham's most historic streets - Drury Hill

Nottingham's historic network of tightly-winding streets was badly damaged by 1960s development, said its civic society.

The 1963 dual carriageway Maid Marian Way - described by Arthur Ling, professor of town planning at the University of Nottingham as "one of the ugliest streets in Europe" - bisected the roads that connected the city with its castle, bulldozing through several medieval streets.

The civic society says the Broadmarsh shopping centre and its surrounding car parks form "a bizarre gateway" to Nottingham

Other historic lanes, including the 4ft-wide Drury Hill, were destroyed by the development of the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre, a 1970s complex. The civic society described this loss as "sinful" and said the now half-empty centre makes "a bizarre gateway" to the city.

It said the Grade I Nottingham Castle can also confuse visitors, who arrive in the city expecting to find medieval ruins rather than a Victorian mansion.

"It's not medieval, it doesn't look medieval and it's never going to look medieval," said Ian Wells, from Nottingham Civic Society.

The city council's design guide admits the city's historic character, which was at its peak in the 1930s, has been "undermined by unsympathetic development".

Guillermo Garma Montiel, principal lecturer in architecture at Nottingham Trent University, said: "The development in the 60s and 70s destroyed some of the city's character.

"Maid Marian Way is quite a scar. It's a deep cut in the fabric of the city. It cuts off Nottingham Castle and the Park from the rest of the city. The buildings that grew up along it have been built without careful consideration for the rest of the city.

He also believes the city's two main shopping centres to have been badly judged.

"They are very bland and need a lot of work," he said. "The Victoria Centre was built in a former railway station, which was a great opportunity, but it was converted really poorly, while the Broadmarsh completely broke the connection that ran from the market square to the railway station."

However, Mr Wells believes Nottingham's heritage got off lightly during the 1960s and 1970s.

"The local authorities made the usual mistakes with the roads," he said. "But they were planning to do worse." A proposed route called Sheriff's Way would have seen the destruction of large parts of the Lace Market and Green's Windmill, he said.

What remains in the city is, many agree, a pleasing mixture of the strikingly modern and the traditional - and when the two work together, they achieve a surprising harmony. More modern buildings, such as Nottingham Playhouse, are praised by architects for the "considered" nature of their design.

"Nottingham is a historic city but its urban fabric has been enhanced by some of the more recent developments," said Mr Montiel.

Nottingham's council is also in talks with English Heritage to enhance its Georgian and Victorian buildings. Any scheme would, it hopes, complement the city's existing Gothic Victorian architecture in residential areas like The Park.

The civic society believes investment in "old Nottingham" could, potentially, kick-start the city's tourism industry by capitalising more on the Robin Hood legend.

"We have a lot of things we could make more of," said Mr Wells.

"A lot of the best stuff in the city is dotted about. If we can find a way of making people more aware of it, and the city's heritage, that could only be a good thing."

Leicester

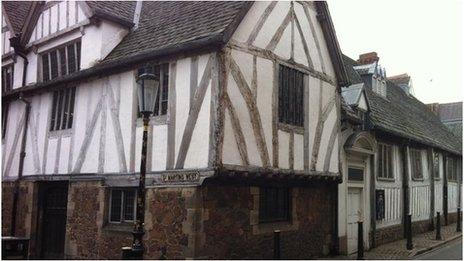

Leicester's Grade I-listed Magazine Gateway, dating from around 1410, was an entrance to the castle

However, more modern developments like the Sky Plaza have divided opinion in the city

Leicester's mayor Sir Peter Soulsby calls the 1960s development that spiralled across the city "council vandalism".

In particular, he blames the city's ring road for severing its historic centres.

The council has launched a £15m project to improve pedestrian access between Leicester's "hidden treasures".

The civic society hopes the scheme will generate more tourism in the city - helped by catalysts such as the discovery, in February, of the remains of the "lost" King Richard III and Leicester's bid to become a city of culture.

"Leicester isn't in the same category as York or Bath but it could make more of itself," said Stuart Bailey, chair of the civic society. "It has a history of running itself down.

"We have 2,000 years of history and examples of architecture from almost every period of that history. The city's heritage could be much more celebrated."

However, Trevor Locke, editor of online magazine Arts in Leicestershire, said he feels it is important money is not spent solely on the fabric of the city.

"Heritage and culture are big drivers of the economy and they will bring tourists into the area," he said.

"But I feel people are more likely to come to Leicester to see and take part in events than to look at buildings.

"It's not just about saying, 'We have a historic Guildhall' - it's about what we do with that Guildhall."

'A mistake to compete'

But could one of these three East Midlands cities ever stand alone as a heritage destination, ranking alongside near-neighbour Lincoln, for example?

Experts think it is unlikely.

"It would be a mistake for these cities to try to compete with places like York, Lincoln and Bath," said Mr Montiel.

"York almost preserves the city in its history. But I definitely think the heritage of English cities needs to be celebrated. In the cases of Nottingham, Leicester and Derby, you can still see that medieval history in their fabric.

"There is definitely a case for making the best of their heritage, as well as recent innovations. And if they could somehow do this as a region, that would enhance their reputation nationally."

Could Leicester ever compete with Lincoln or York as a heritage destination?

David Else, lead author of the Lonely Planet guide to Great Britain, agrees the three counties need to work together to promote their heritage.

"You're not going to get somebody flying across the Atlantic just to go to Derby," he said. "And I think it's important not to pretend they're something they're not. If people come expecting dreaming spires, they are going to be disappointed.

"I think it would be a great idea if the three cities worked together to promote themselves.

"One of them alone might not be a York or an Edinburgh as far as tourists go, but together - and particularly if you factor in their surrounding countryside - they could be greater than the sum of their parts."

- Published7 September 2013

- Published29 August 2013