Seven of the more unusual areas of university research

- Published

Dr Matt Lodder hopes his research will help get tattooing established and appreciated as "art"

University research in a wide range of areas keeps the "UK ahead in the global race", according to the government. But the Institute of Fiscal Studies, external (IFS) warns of possible research funding cuts if student enrolment numbers remain the same. How broad is the research?

Universities will tell you research transforms our lives, external.

Sometimes the outcomes are obvious: the human genome project, for example, or the discovery of antibiotics. But much research passes into the annals of human knowledge largely unnoticed.

The IFS study, funded by Universities UK, warned that the government "might have to take the difficult decision not to protect science and research spending" in coming years.

The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, however, has vowed to support research.

A spokeswoman said: "Its broad range of activities play a vital role in keeping the UK ahead in the global race."

Here are seven of the more unusual areas of study within that "broad range".

The footwear expert: Professor Giorgio Riello, University of Warwick

The laces of Prof Riello's academic career have been firmly tied to the history of footwear.

Although his most recent book is about cotton, he remains one of the world's leading experts on the history of shoes.

And earlier this year - at an international footwear symposium - he was the keynote speaker, delivering a saucily titled talk on The Art of the Shoe: Poetry and Pornography of a less-than-pedestrian artefact.

Prof Riello says shoes are a "lens" through which the cultural, social and scientific past can be seen.

He says shoes have been made - and, of equal importance, bought - for an unusually wide range of reasons, from the functional to the erotic.

The erotic includes what Prof Riello describes as the "artistic" aspect of footwear.

Footwear and fetish have long been entwined, says the University of Warwick's Dr Giorgio Riello

These shoes cannot be worn, or cannot be worn as shoes for walking. Instead, such shoes might be worn only in the horizontal position in the bedroom.

The fly expert: Dr Barry Denholm, University of Cambridge

Disbelief is the most common response Dr Barry Denholm gets when he tells people about his research.

Studying in the basement of Cambridge University's Zoology Department, Dr Denholm doesn't just study flies: he studies cells in their excretory system.

Called nephrocytes, these cells have an uncanny similarity with the podocyte cells of our own kidneys.

Dr Barry Denholm says kidney research has been made quicker and cheaper by flies

"I usually get a response like, 'you're telling me a fly has a kidney?' And then I tell them they have to pee and their bodies have to filter out waste just like ours do.

"They have brains, hearts and their equivalent to lungs. We can learn a lot from them."

This recently discovered similarity between the fly and human excretory cells means kidney research can be done more cheaply and quickly.

That research is at an early stage.

"We are looking at how the genes work. If we want to understand kidney disease, we need to understand what a certain gene usually does."

Asking those questions, says Dr Denholm, paves the way to asking the ultimate question - whether a certain disease can be "fixed".

The tattoo expert: Dr Matt Lodder, University of Essex

"I love news headlines," says Dr Matt Lodder, of the University of Essex.

And he produces a news story from 2011 which proclaims tattoos are the new "big thing" and no longer the preserve of "bikers and sailors".

Then he presents another news cutting. It has an almost identical headline. And another. And another.

These different cuttings span more than a century and reveal something of which we can all be certain: tattoos are not a fad and have never been the sole preserve of bikers and sailors.

Dr Lodder has delved into the primary source material of tattooing - the machines and needles used, the design books and the adverts of old.

He hopes not only to challenge the many myths and false assumptions people make and perpetuate about tattooing, but to help get tattooing established and appreciated as "art" alongside other media such as sculpture and painting.

Female bodybuilding: Dr Tanya Bunsell, St Mary's University College

Dr Tanya Bunsell immersed herself in the subculture of female bodybuilding

Some struggle with the idea of muscular women.

Dr Tanya Bunsell, who studies female bodybuilding, can list the most common words she encounters. They include "sick", "unnatural", "disgusting", "he-she" and "unattractive".

Such words are rarely applied to men who build their muscles.

The question for Dr Bunsell is simple: why? Why do so many people respond so strongly to female bodybuilding and why, in light of the negative sobriquets, do women bodybuilders pump iron?

To find out, Dr Bunsell "immersed herself in the subculture" for more than two years in order to "live and feel" the bodybuilding life.

What she found was a mix of self-healing, bodily pleasure, catharsis and control. And sometimes women bodybuild simply because they enjoy it and/or are good at it.

None of the women worked out either to lose weight or to become more attractive to men.

And if it seems an unusual subject of study, consider the public's appetite for stories about celebrity bodybuilders including Jodie Marsh, Madonna and Holly Walcott.

Society's curiosity is there. Dr Bunsell's role is in replacing our assumptions with knowledge.

The lap-dancing expert: Dr Rachela Colosi, University of Lincoln

Lap dancing clubs are not just about titillation, says Dr Rachela Colosi

Long before the PhD, Dr Rachel Colosi worked as a lap dancer.

"I did not think I would become an academic," she says. "I thought maybe I would work in the sex industry.

"I went back and did a master's degree because I didn't know what else to do, and then I did a PhD."

The result was an ethnography of a community of lap dancers at the place where Dr Colosi once worked.

Her past gave her the type of access which would not have been available to an outsider.

What she found was a defined community of women, with its own set of rules, hierarchy, rites of passage (from "new girl" to "old school") and language.

A community, she said, strengthened and possibly defined, in part, by outsiders' view of lap dancing as "deviant".

Her work, she says, is important academically, not just as a piece of ethnography but in the way it was carried out - by an insider rather than an outsider.

She hopes it will also be publicly useful, in guiding policy about lap dancers and the establishments they work in.

The cow tracker: Dr Jonathan Amory, Writtle College

Do cows have friends? Do they take themselves off away from the herd when they are feeling poorly?

These are questions Dr Jonathan Amory hopes one day soon to answer.

Writtle College's principal lecturer in animal behaviour and welfare, Dr Amory has been studying a single dairy herd in Essex using local positioning devices capable of telling him when cows are standing up, where they are and even which way they are facing.

The small devices are attached to a sturdy webbing collar with a weight on one end to keep it in place.

The cows are initially interested in each others' collars and give them a lick and then get used to them.

"It is more a novelty thing for them," said Dr Amory.

In the new year, he will begin collecting data for the devices.

Dr Amory with one of the devices used to track the movement of a cow

"Now we can know not only what she is doing, but where is she doing it and, here's the new question, who is she doing it with. We can look at the whole social network and whether cows have friends or indeed if they have enemies.

The long-term aim of the project has both economic and welfare goals.

"We're trying to produce an early warning system for disease," said Dr Amory. "Early detection is absolutely vital."

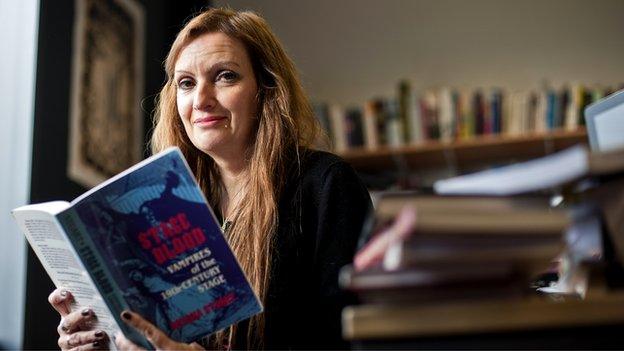

The 'coffin boffin': Dr Sam George, University of Hertfordshire

No, Dr Sam George does not believe in vampires.

But she does believe that literary vampires - meant to cast no reflection - actually reflect the cultural worlds from which they emerge.

Dr George runs an MA module called Reading the Vampire, at the University of Hertfordshire, and is the convener of an interdisciplinary research project Open Graves, Open Minds: Vampires and the Undead in Modern Culture.

"People think vampires are very contemporary with the likes of Twilight, but one of the things you become aware of when you investigate the genre is just how long they have endured."

Long before Bram Stoker penned Dracula in the 1890s, audiences were gripped with folkloric tales of undead figures in peasant communities in eastern Europe.

Dr Sam George said her course in vampires had its "detractors and scoffers"

Asked why vampire studies matter, Dr George admits it is a question commonly asked - and one often raised by those in business studies.

The answer, for Dr George, lies in the longevity and popularity - and therefore relevance - of the genre.

"Bringing vampires into the curriculum has proved controversial for some. We have had our scoffers and detractors, but I wanted to provide a platform to investigate these creatures in all their various manifestations and cultural forms.

"It is important to keep challenging the canon and show that you can study popular literature in a serious way."

- Published21 October 2013

- Published10 September 2013

- Published11 September 2012