World War One: Chiseldon training camp's soldiers with VD

- Published

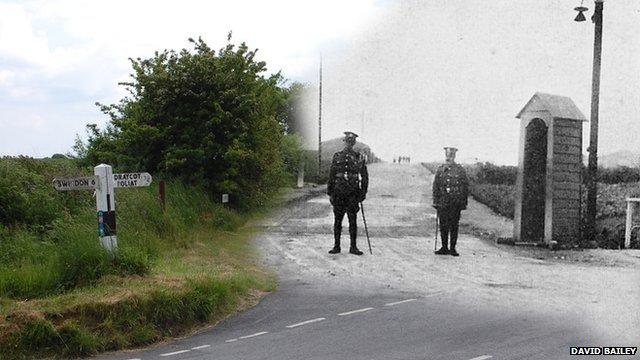

Guards at the main gate to Chiseldon Camp and how the area looks now

More than 400,000 soldiers contracted venereal diseases (VD) during World War One, despite warnings to "resist temptations" and "avoid intimacy". Those treated at an army training camp base in Wiltshire - known locally as the bad boys' camp - were kept behind barbed wire and forced to wear blue uniforms. But, they still managed to get female company.

Almost nothing remains of Chiseldon Camp in Wiltshire, set up in 1914 as a training base for up to 10,000 troops at a time, before they went to the front.

The surrounding countryside and the railway line running through the camp, linking it to the Midlands to the south coast, made it an ideal location.

In 1915, part of it was developed into a hospital for wounded soldiers before, in 1916, it began to treat soldiers coming back from the front who had contracted VD.

When war had been declared, Lord Kitchener had warned troops serving abroad "you may find temptations, but you must entirely resist them".

He urged British soldiers to treat all women "with perfect courtesy", but avoid "any intimacy".

But the blue-uniformed soldiers who, from July 1917, were kept behind 6ft-high barbed wire fences in a special area of Chiseldon, called L Lines, were proof that for some, Kitchener's appeals fell on deaf ears.

In 1918 alone, more than 60,000 soldiers needed treatment for VD - compared to around 75,000 who were treated for trench foot in the whole of the war.

'Naughty ladies and bad boys'

Sheila Passmore, of Chiseldon Local History Group, said that despite the barbed wire and guards, troops could still indulge the vices that led them there in the first place.

A shanty camp known as Piccadilly sprang up alongside the perimeter fence with shops and cafes for the troops.

"Ladies from Swindon used to get the early train, known locally as the meat train, and come down to Piccadilly and 'entertain' soldiers from the camp whenever they got the chance," according to Mrs Passmore.

"There were one or two tradesmen in the village who would, rather naughtily, pick up the officers, because they were paid.

"They would be covered up in the cart and would nip into Swindon to enjoy themselves.

"So we had naughty ladies and bad boys," she said.

Treating the VD cases had a real impact on the army's fighting strength, according to Professor Mark Harrison from Oxford University.

"It was an enormous drain on manpower because troops would normally be treated for around a month and that took a lot of people away from the battlefield," he said.

Soldiers who contracted VD would not be paid while they were being treated, and would also lose the right to take leave for a year.

Mr Harrison said that initially the army also wrote to the soldier's family spelling out what he was being treated for.

"That was stopped sometime around 1916, after a major committed suicide after his wife had been informed," he explained.

-chiseldoncamp1915.jpg)

The shanty town know as Piccadilly that sprang up next to Chiseldon Camp

Historian David Bailey, who has written a book on Chiseldon, said the soldiers being treated for VD were kept away from locals and other soldiers.

"All four sides [of L Lines] were bounded by a six foot high barbed wire fence - effectively it was a prison camp."

'Wrong decisions'

The railway line linking the camp to Southampton also cut off the VD wards from the rest of the camp.

The treatments the soldiers received were "pretty horrendous", according to Mr Bailey, involving injecting arsenic and the use of a mercury-based cream - "substances that no-one would dare use nowadays".

In other ways, the village benefited from the presence of the camp - the army set up a cinema which was also open to locals, with children sitting cross-legged at the front.

But, those same children were warned to avoid men in blue uniforms, according to Mrs Passmore, with the military police summoned on occasions to round up any escapees.

The camp continued as an army base after World War One, then closed in 1962 when national service ended, and was demolished ten years later.

In 1992, the Chiseldon Local History Group put up a memorial plaque to "the men and women of all nations who passed this way".

But Mr Bailey still has mixed feeling about the bad boys in blue uniforms.

"I don't exactly sympathise with their plight, because like the army I think of it as a self-inflicted wound, but I can understand why they did it," he said.

"A young boy, away from home, 18 or 19 years of age, about to go into battle, wants to sample life, and maybe he made the wrong decision."

Hear why the locals were kept out of the 'bad boys' camp and find out more from Dr Saleyha Ahsan on how WW1 changed military medicine.

Warfare historian Dr Clare Makepeace describes how visiting brothels was a key part of World War One soldier's experience.