Winchester Whisperer: The secret newspaper made by jailed pacifists

- Published

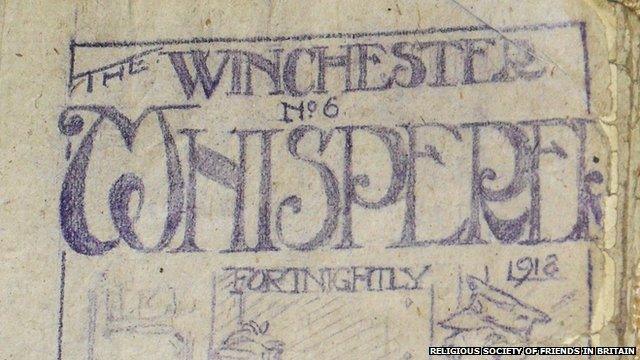

The newspaper was written on toilet paper sewn together with fabric from mail sacks

Around 100 conscientious objectors who refused to contribute to the war effort in any way were jailed during World War One. Despite rules forbidding them to even talk to other prisoners one pacifist managed to produce a secret newspaper written on toilet paper.

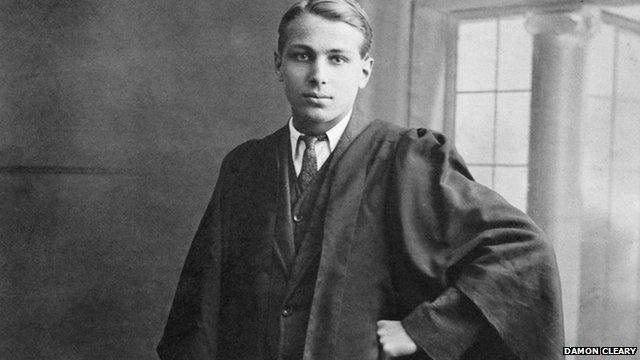

"The hearing was rather a farce - my name was called and I appeared before the tribunal.

"The chairman of the tribunal asked me how old I was - I said I was 18 years of age and he said [that] in that case you're not old enough to have a conscience - case dismissed."

The chairman may have dismissed Harold Bing's request to be classed as a conscientious objector, but he clearly did not think he was too young to go to war.

Mr Bing soon found himself arrested and being held at Kingston Barracks.

After continuing to refuse to regard himself as a soldier, his long imprisonment as an absolutist conscientious objector (CO) began - it was 1916.

His moral stance that he would not contribute to the war effort in any way meant he would stay in jail until 1919.

'Hidden up sleeves'

But, his incarceration did not stop him expressing his opinions on the war.

The Winchester Whisperer was a newspaper he and other pacifists produced in secret using hidden ink, needles as pens and toilet paper.

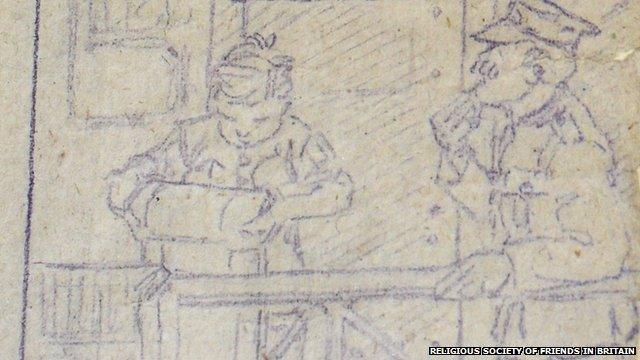

"Different people wrote little essays or poems, humorous remarks, or sometimes little cartoon or sketches," Mr Bing remembered in 1974 interview held by the Imperial War Museum.

"As it happened no copy of The Winchester Whisperer was ever captured by the warders, though I think some of them suspected its existence."

The fragile paper was bound together using canvas from mailbags and passed around the jail "hidden under people's waistcoats or up their sleeves".

COs who were not absolutists might not fight, but agreed to work in a support role at the front or risked their lives in the Friends' Ambulance Unit.

Others would only join labour units in the UK, doing non-military work such as forestry or agriculture.

The newspaper contained drawings, articles, humour and poetry

Many of them also worked in Dartmoor Prison, renamed the Princetown Work Centre - one of a number of Home Office-run centres. The locks were removed and men were allowed out on curfew after work.

But, absolutists like Bing would not wear a uniform, obey orders or take part in anything connected to the war.

After spells at cells at Kingston barracks and Wormwood Scrubs, he spent most of his sentence doing hard labour at Winchester's jail, secretly producing the Whisperer.

No writing materials

"Under a hard labour sentence, which was the severest form of sentence in the British legal system, the first month was spent in solitary confinement in the cell," he recalled.

"One got out for half an hour's exercise or so each day, and we were not allowed to talk to anyone else.

"We marched around the exercise yard at least a yard apart with several warders supervising to see that we didn't communicate.

"Apart from that, the whole time was spent in the cell."

The COs communicated using Morse code tapped out on heating pipes between the cells - some even played chess games this way, he said.

They were allowed no writing materials in the cell other than chalk and a slate, and were only given limited access to pen and ink when they were allowed to write letters.

The lack of pen and paper meant that producing a newspaper required a little ingenuity.

Ink was siphoned off and hidden in improvised pots made in the balls of wax prisoners were given as part of their work making mail sacks.

"With inkpots of that kind [we] produced at Winchester Prison a periodical called The Winchester Whisperer," Mr Bing recalled in an interview recorded in 1974.

"It was written on the small brown sheets of toilet paper with which we were supplied.

Harold Bing was 18-years-old when he first appeared before a tribunal

"I used as a pen a needle, writing with the hollow end, dipping it into the ink - this meant of course that one had to be dipping the needle into the ink for almost every word.

"But it did produce thin writing which meant you could get a good deal onto one sheet of toilet paper."

Similar magazines were produced at other jails where COs were held, including the Canterbury Clinker and the Old Lags' Hansard at Wandsworth Jail.

One fragile copy of the Winchester Whisperer has been preserved by The Society Of Friends (Quakers).

David Blake, head of library and archives for the Quakers, calls it an "amazing document".

"The effort that has gone into it, the skill that is there - [it] was a mixture of their religion and their thoughts about issues," he said.

"I think it's important because it shows there were people who felt very, very strongly about the issues and were prepared to be in prison."

After his release, Mr Bing decided to pursue a career in education, but found wartime prejudices against "conshies" lingered on.

"At that times if you looked through the job advertisements in the Times Education Supplement, very often at the head of the advert it said no conscientious objectors need apply - [there was] advert after advert had that," he said.

However, the same tenacity that had created the Winchester Whisperer ensured he did eventually become a teacher, and finished his career as a lecturer at the Co-operative College in Loughborough.

Find out more about how the Winchester Whisperer was passed around Winchester Prison and how 12 million letters a week got through to the front with Alan Johnson.

- Published30 April 2013

- Published1 August 2013