World War One: Thomas Highgate first to be shot for cowardice

- Published

Thomas Highgate - casualty, coward or victim?

He was caught, tried and shot "as publicly as possible" within 48 hours, in the first few weeks of World War One. The 19-year-old soldier's grave is lost and his name is not on the war memorial in his birthplace.

Thomas James Highgate was the first British soldier to be executed for desertion in WW1.

His fate still provokes fierce emotions and difficult questions.

Terence Highgate, great-nephew of Thomas, has been campaigning for years to clear his name.

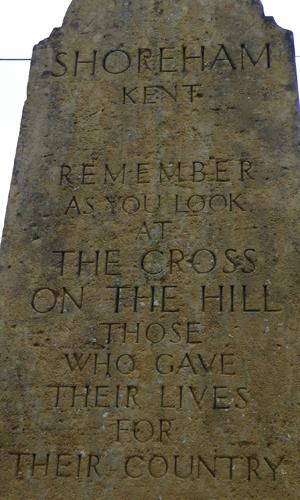

He feels the village memorial, and its reference to a nearby chalk cross, make his case.

"It says; 'Shoreham, Kent, remember as you look at the cross on the hill, those who gave their lives for their country 1914 - 1918'," said Mr Highgate.

"He was one of them and his name should be on there."

After initial clashes at the Belgian town of Mons in August 1914, the British army was forced into a two-week, exhausting, retreat.

'Army on run'

Julian Putkowski, historian and author of Shot at Dawn, outlined how Pte Highgate made what would turn out to be a fatal decision, in the early hours of 6 September.

"The British army was on the run," he says. "Highgate falls out and asks permission to 'ease himself', to defecate basically.

"That's it really, that's his desertion. No more than an hour or two, or a few hours at any rate."

Later the same day and almost before he was officially reported missing, Pte Highgate was found in the grounds of a chateau, dressed in civilian clothes.

His court martial, convened within hours, heard he confessed to a gamekeeper, "I have had enough of it, I want to get out of it and this is how I am going to do it".

Forced to defend himself, Pte Highgate disputed that evidence and insisted he had intended to rejoin his unit.

However, he could not explain why he had taken off his uniform, saying only that his memory was unclear.

'Crisis of confidence'

A guilty verdict was returned almost immediately.

Highgate was shot just after 07:00 on 8 September, in front of soldiers from two other units.

Mr Putkowski: "If one looks at the time Highgate deserts, the countryside is littered with stragglers, just like him, and they weren't executed.

"I have the feeling that what we are looking at here is a crisis of confidence amongst the senior officers and not necessarily anything to do with Highgate himself."

Those shots echo still.

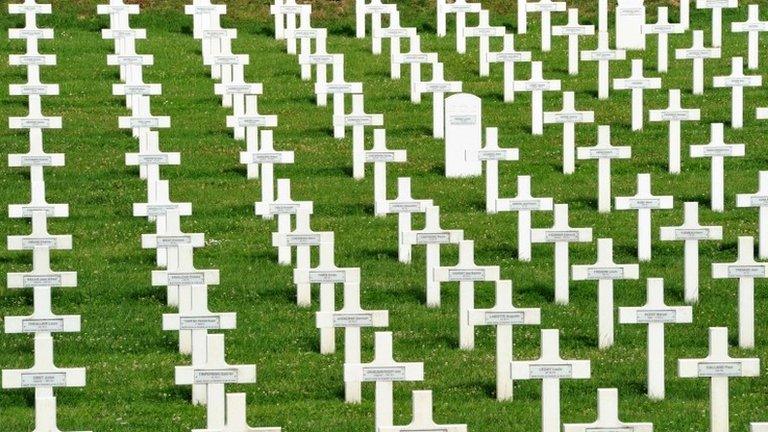

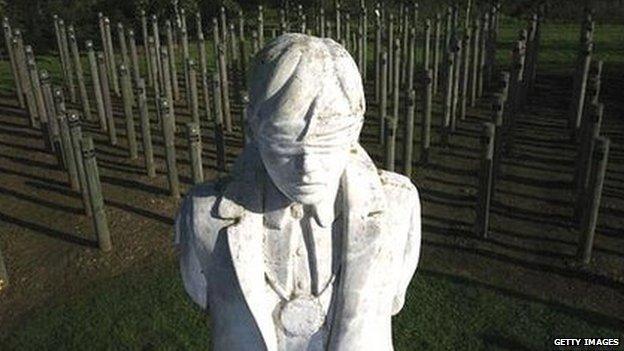

The Shot at Dawn sculpture at the National Memorial Arboretum commemorates the 306 men shot for desertion or cowardice in World War One

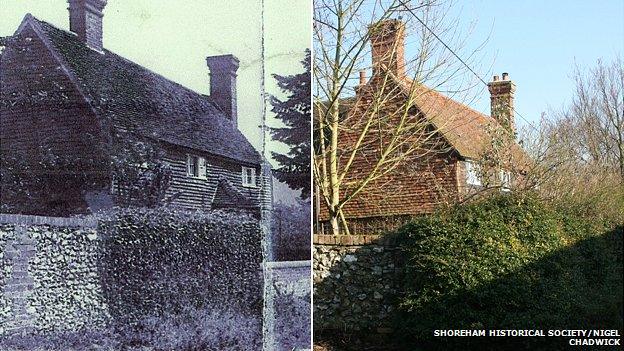

Thomas Highgate's birthplace has outwardly changed little in 100 years

When the village memorial was built in the 1920s the family did not, according to the Royal British Legion, ask for his name to be included.

In the year 2000, the church held a poll on the issue, and of those taking part, the vast majority backed adding Highgate's name.

Six years later, 306 British or Empire soldiers executed for cowardice or desertion (but not those guilty of mutiny or murder), received a blanket pardon.

Yet, still a space remains on Shoreham's memorial where Pte Highgate's name could go.

Maj Michael Green, president of the local branch of the Royal British Legion, said the issue has been repeatedly discussed.

Hasty justice?

"They feel that as a deserter he shouldn't be included. He wasn't killed [in the fighting], he was killed as a deserter," he said.

"I don't see why he should be included on the war memorial with those that actually served and died in the course of duty.

"We will continue to discuss it but I feel it sets a poor precedent. But, that is my view and not necessarily the final view."

Most memorials were put up independently and criteria for inclusion varied widely

Pte Highgate's case shows the difficulties of judging past decisions by current standards.

His trial, hasty and one sided by civilian standards, was conducted in line with emergency wartime military procedures.

Death sentences had to be approved by the commander-in-chief, who was expected - required even - to take the prevailing military situation into account.

And that situation was, by 5 September, that the British Expeditionary Force had lost 20,000 men - nearly a quarter of its strength - killed, wounded, missing and unaccounted for.

Orders from the top said "stragglers" without a good story would face "severe punishment".

On a personal level for Pte Highgate, it is rather more complex.

The 19-year-old, who joined the army in early 1913, had a poor military record, including previous absences. He had even served 42 days imprisonment for desertion - but was only caught when he tried to join a different army unit closer to one of his brothers.

A medical report just weeks before war began found he suffered from confusion and memory lapses, possibly related to contracting yellow fever while serving on a ship.

Mark Connelly, Professor of Modern British Military History at the University of Kent, warns against rewriting the past.

'Overturn judgement?'

"Let's say in 20-30 years time some German families say 'My great grandfather was in the Second World War and he was executed because he was involved in some Nazi atrocities," he said.

"'But we all know that until he joined the forces he was just a young man who was passionate about his country but didn't really have a political ideology, but was then seduced by the Nazi ideology.

"'We as a family would like to expunge that record'.

"Would we feel comfortable overturning judgements like that?"

The family, which lived in extreme poverty, moved between Shoreham and the fringes of London. Thomas, and two of his brothers who also died at the front, are included on a memorial in Sidcup.

But Terence Highgate insists he should also be remembered in Shoreham.

"Since he has been cleared and free, his name should be on [the memorial]," he said.

"It's not, so I have put up a cross in his name and it will stay there for ever and ever."

How an Essex soldier was denied recognition for his services because of his background and explore why we remember the poets of WW1 rather than the composers.

- Published1 October 2013