War At Home: Brighton Pavilion's hospital for Indian troops

- Published

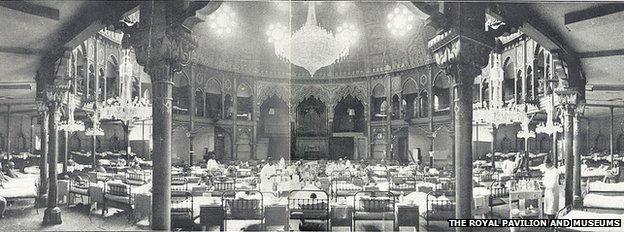

The Pavilion was built as a royal pleasure palace but by 1914 was mostly empty and unused

The Brighton Dome, close to the Pavilion, once hosted beds but now is more used to welcoming bands

Whatever was going through the head of Prince George, the vain and indulgent son of King George III, when he commissioned the monumental folly that is the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, in 1787 it almost certainly was not "military hospital".

And not just any military hospital. A hospital to care for troops from the jewel in the crown, India.

How did thousands of Indian troops end up here? Why was this opulent fantasy building chosen? And, how did such an influx go down in a south coast seaside resort?

Most historians agree total war caught Britain's army underprepared. Its 120,000 strong expeditionary force was pitifully small compared with the millions fielded by France, Germany and Austria.

Kevin Bacon, from Brighton Museums, says the shortage threatened to knock Britain out of the war.

"Swarms of volunteers would take time to train," he said.

"The generals looked to the Empire and in India it had a large force that was well trained and could be deployed relatively quickly."

The first 28,500 Indian Army troops arrived in France on 26 September, just eight weeks after war began.

White elephant

Fighting means casualties, who need treatment - somewhere close to the ports where the hospital ships docked.

The Pavilion came into the picture mainly because of its sheer oddness. Sold by a puritanical but practical Queen Victoria in 1850, the town of Brighton had wondered what to do with it ever since.

The presence of white female nurses was one of the many extraordinary features of the hospital

In 1914, Mr Bacon said, the Pavilion was still going spare.

"The army was originally looking at hotels but the civic authorities suggested they could use this building," he explained.

"And it came cheap. Unlike hotels where the proprietors had to be recompensed for their time, the Pavilion was a civic building without any clear purpose."

Along with a nearby workhouse - swiftly renamed the Kitchener Hospital - and the Dome and Corn Exchange, near the Pavilion and built to a similar style, the government took over.

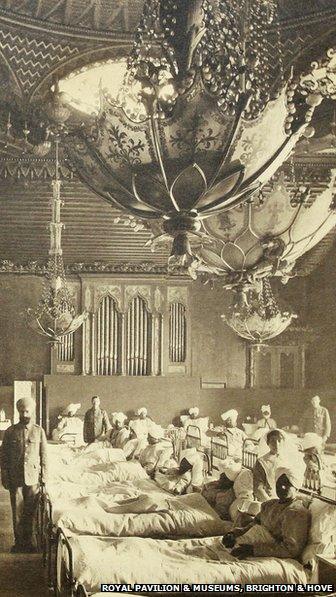

During the conversion to a hospital, officials were acutely aware the troops were not simply Indian but also practising Muslims, Hindus or Sikhs.

'Fairyland' treatment

Tom Donovan, Brighton historian, said: "This led to three different types of kitchens, there were nine in all, to observe dietary rules. There was also a Sikh temple in a tent in the gardens and a room for the Muslims to pray to Mecca.

"Because of the caste system, where different castes would not share the same taps or toilets, three different types had to be installed in each ward so men could comfortably share a ward."

Beneath the chandeliers, patients were also entertained with music performances and magic lantern shows.

Medical care met the standards of the sumptuous decor. Soldiers wrote of being "tended like flowers", of "never being so happy" and called the hospital "a fairyland".

So had war banished colonial and racial divisions? Probably not.

An unheard of move to have Indian soldiers tended by white, female nurses was quickly halted, according to Santanu Das, an expert in World War One literature at King's College London.

He says: "They were then used in a supervisory capacity only, while the actual nursing was done by male orderlies.

"It has to do with keeping up the prestige of the Empire, the idea of English nurses looking after Indian sepoys was somehow detrimental, especially back in the colonies."

And how the treatment of troops was reported was of great importance to the colonial rulers of the volatile, increasingly confident sub-continent.

'Funeral pyres'

"So perhaps the end is propaganda but in the process they are getting good care with an extraordinary degree of sensitivity to the cultural differences among the communities. They loved Brighton," Mr Das said.

And did apparently uptight Brighton love them back?

Mr Donovan explains: "Early on [the soldiers] were allowed to go out on their own and they did mix and mingle with Brightonians and there are fond memories of this period.

"They would be invited to people's houses to eat and meet the family, and would be taken out to see the sights.

"But there was a certain amount of what was - to the British - unpalatable racial integration where white women and soldiers became friends.

"There were also lots of lowlife places like pubs and dens of iniquity, where the Indians, it was felt, were going too often."

Trips out became chaperoned and the Pavilion gardens were fenced in.

Patients were lavished with attention by the public and the authorities responded by chaperoning all trips outside the hospital

"Though I believe there are stories of them getting over the fences to have night time shenanigans," says Mr Donovan.

The Pavilion had a capacity of nearly 600 and about 4,000 soldiers were treated in two years. Together with the Kitchener and the Dome, more than 12,000 Indian soldiers were cared for.

Special provision was also made for those who succumbed to their wounds.

Fifty-three Gurkha, Hindu and Sikh soldiers were cremated, in line with their traditional practices, on the South Downs near Patcham and their ashes scattered in the sea.

Woking Mosque received the bodies of 21 Muslim soldiers.

The end came when most of the Indian forces were moved from France to fight in the Middle East.

The Pavilion then cared for limbless soldiers and the Kitchener looked after Canadian casualties.

Both reverted to civilian use in 1920. The Kitchener is now the Brighton General Hospital, the Dome is a concert and events venue and the Royal Pavilion, restored to its 18th Century glory, is a major tourist attraction.

Hear about the WW1 experiences of Sikhs from Coventry and question whether history has misjudged the generals of WW1.

- Published24 December 2013

- Published13 November 2013

- Published6 August 2013